Git Tools

By now, you’ve learned most of the day-to-day commands and workflows that you need to manage or maintain a Git repository for your source code control. You’ve accomplished the basic tasks of tracking and committing files, and you’ve harnessed the power of the staging area and lightweight topic branching and merging.

Now you’ll explore a number of very powerful things that Git can do that you may not necessarily use on a day-to-day basis but that you may need at some point.

Revision Selection

Git allows you to specify specific commits or a range of commits in several ways. They aren’t necessarily obvious but are helpful to know.

Single Revisions

You can obviously refer to a commit by the SHA-1 hash that it’s given, but there are more human-friendly ways to refer to commits as well. This section outlines the various ways you can refer to a single commit.

Short SHA-1

Git is smart enough to figure out what commit you meant to type if you provide the first few characters, as long as your partial SHA-1 is at least four characters long and unambiguous – that is, only one object in the current repository begins with that partial SHA-1.

For example, to see a specific commit, suppose you run a git log command and identify the commit where you added certain functionality:

$git logcommit 734713bc047d87bf7eac9674765ae793478c50d3Author: Scott Chacon <schacon@gmail.com>Date: Fri Jan 2 18:32:33 2009 -0800fixed refs handling, added gc auto, updated testscommit d921970aadf03b3cf0e71becdaab3147ba71cdefMerge: 1c002dd... 35cfb2b...Author: Scott Chacon <schacon@gmail.com>Date: Thu Dec 11 15:08:43 2008 -0800Merge commit 'phedders/rdocs'commit 1c002dd4b536e7479fe34593e72e6c6c1819e53bAuthor: Scott Chacon <schacon@gmail.com>Date: Thu Dec 11 14:58:32 2008 -0800added some blame and merge stuff

In this case, choose 1c002dd.... If you git show that commit, the following commands are equivalent (assuming the shorter versions are unambiguous):

$git show 1c002dd4b536e7479fe34593e72e6c6c1819e53b$git show 1c002dd4b536e7479f$git show 1c002d

Git can figure out a short, unique abbreviation for your SHA-1 values.

If you pass --abbrev-commit to the git log command, the output will use shorter values but keep them unique; it defaults to using seven characters but makes them longer if necessary to keep the SHA-1 unambiguous:

$git log --abbrev-commit --pretty=onelineca82a6d changed the version number085bb3b removed unnecessary test codea11bef0 first commit

Generally, eight to ten characters are more than enough to be unique within a project.

As an example, the Linux kernel, which is a pretty large project with over 450k commits and 3.6 million objects, has no two objects whose SHA-1s overlap more than the first 11 characters.

Note

A SHORT NOTE ABOUT SHA-1

A lot of people become concerned at some point that they will, by random happenstance, have two objects in their repository that hash to the same SHA-1 value. What then?

If you do happen to commit an object that hashes to the same SHA-1 value as a previous object in your repository, Git will see the previous object already in your Git database and assume it was already written. If you try to check out that object again at some point, you’ll always get the data of the first object.

However, you should be aware of how ridiculously unlikely this scenario is.

The SHA-1 digest is 20 bytes or 160 bits.

The number of randomly hashed objects needed to ensure a 50% probability of a single collision is about 280

(the formula for determining collision probability is p = (n(n-1)/2) * (1/2^160)). 280

is 1.2 x 1024

or 1 million billion billion.

That’s 1,200 times the number of grains of sand on the earth.

Here’s an example to give you an idea of what it would take to get a SHA-1 collision. If all 6.5 billion humans on Earth were programming, and every second, each one was producing code that was the equivalent of the entire Linux kernel history (3.6 million Git objects) and pushing it into one enormous Git repository, it would take roughly 2 years until that repository contained enough objects to have a 50% probability of a single SHA-1 object collision. A higher probability exists that every member of your programming team will be attacked and killed by wolves in unrelated incidents on the same night.

Branch References

The most straightforward way to specify a commit requires that it has a branch reference pointed at it.

Then, you can use a branch name in any Git command that expects a commit object or SHA-1 value.

For instance, if you want to show the last commit object on a branch, the following commands are equivalent, assuming that the topic1 branch points to ca82a6d:

$git show ca82a6dff817ec66f44342007202690a93763949$git show topic1

If you want to see which specific SHA-1 a branch points to, or if you want to see what any of these examples boils down to in terms of SHA-1s, you can use a Git plumbing tool called rev-parse.

You can see Git Internals for more information about plumbing tools; basically, rev-parse exists for lower-level operations and isn’t designed to be used in day-to-day operations.

However, it can be helpful sometimes when you need to see what’s really going on.

Here you can run rev-parse on your branch.

$git rev-parse topic1ca82a6dff817ec66f44342007202690a93763949

RefLog Shortnames

One of the things Git does in the background while you’re working away is keep a “reflog” – a log of where your HEAD and branch references have been for the last few months.

You can see your reflog by using git reflog:

$git reflog734713b HEAD@{0}: commit: fixed refs handling, added gc auto, updatedd921970 HEAD@{1}: merge phedders/rdocs: Merge made by recursive.1c002dd HEAD@{2}: commit: added some blame and merge stuff1c36188 HEAD@{3}: rebase -i (squash): updating HEAD95df984 HEAD@{4}: commit: # This is a combination of two commits.1c36188 HEAD@{5}: rebase -i (squash): updating HEAD7e05da5 HEAD@{6}: rebase -i (pick): updating HEAD

Every time your branch tip is updated for any reason, Git stores that information for you in this temporary history.

And you can specify older commits with this data, as well.

If you want to see the fifth prior value of the HEAD of your repository, you can use the @{n} reference that you see in the reflog output:

$git show HEAD@{5}

You can also use this syntax to see where a branch was some specific amount of time ago.

For instance, to see where your master branch was yesterday, you can type

$git show master@{yesterday}

That shows you where the branch tip was yesterday. This technique only works for data that’s still in your reflog, so you can’t use it to look for commits older than a few months.

To see reflog information formatted like the git log output, you can run git log -g:

$git log -g mastercommit 734713bc047d87bf7eac9674765ae793478c50d3Reflog: master@{0} (Scott Chacon <schacon@gmail.com>)Reflog message: commit: fixed refs handling, added gc auto, updatedAuthor: Scott Chacon <schacon@gmail.com>Date: Fri Jan 2 18:32:33 2009 -0800fixed refs handling, added gc auto, updated testscommit d921970aadf03b3cf0e71becdaab3147ba71cdefReflog: master@{1} (Scott Chacon <schacon@gmail.com>)Reflog message: merge phedders/rdocs: Merge made by recursive.Author: Scott Chacon <schacon@gmail.com>Date: Thu Dec 11 15:08:43 2008 -0800Merge commit 'phedders/rdocs'

It’s important to note that the reflog information is strictly local – it’s a log of what you’ve done in your repository.

The references won’t be the same on someone else’s copy of the repository; and right after you initially clone a repository, you’ll have an empty reflog, as no activity has occurred yet in your repository.

Running git show HEAD@{2.months.ago} will work only if you cloned the project at least two months ago – if you cloned it five minutes ago, you’ll get no results.

Ancestry References

The other main way to specify a commit is via its ancestry.

If you place a ^ at the end of a reference, Git resolves it to mean the parent of that commit.

Suppose you look at the history of your project:

$git log --pretty=format:'%h %s'--graph* 734713b fixed refs handling, added gc auto, updated tests* d921970 Merge commit 'phedders/rdocs'|\| * 35cfb2b Some rdoc changes* | 1c002dd added some blame and merge stuff|/* 1c36188 ignore *.gem* 9b29157 add open3_detach to gemspec file list

Then, you can see the previous commit by specifying HEAD^, which means “the parent of HEAD”:

$git show HEAD^commit d921970aadf03b3cf0e71becdaab3147ba71cdefMerge: 1c002dd... 35cfb2b...Author: Scott Chacon <schacon@gmail.com>Date: Thu Dec 11 15:08:43 2008 -0800Merge commit 'phedders/rdocs'

You can also specify a number after the ^ – for example, d921970^2 means “the second parent of d921970.”

This syntax is only useful for merge commits, which have more than one parent.

The first parent is the branch you were on when you merged, and the second is the commit on the branch that you merged in:

$git show d921970^commit 1c002dd4b536e7479fe34593e72e6c6c1819e53bAuthor: Scott Chacon <schacon@gmail.com>Date: Thu Dec 11 14:58:32 2008 -0800added some blame and merge stuff$git show d921970^2commit 35cfb2b795a55793d7cc56a6cc2060b4bb732548Author: Paul Hedderly <paul+git@mjr.org>Date: Wed Dec 10 22:22:03 2008 +0000Some rdoc changes

The other main ancestry specification is the ~.

This also refers to the first parent, so HEAD~ and HEAD^ are equivalent.

The difference becomes apparent when you specify a number.

HEAD~2 means “the first parent of the first parent,” or “the grandparent” – it traverses the first parents the number of times you specify.

For example, in the history listed earlier, HEAD~3 would be

$git show HEAD~3commit 1c3618887afb5fbcbea25b7c013f4e2114448b8dAuthor: Tom Preston-Werner <tom@mojombo.com>Date: Fri Nov 7 13:47:59 2008 -0500ignore *.gem

This can also be written HEAD^^^, which again is the first parent of the first parent of the first parent:

$git show HEAD^^^commit 1c3618887afb5fbcbea25b7c013f4e2114448b8dAuthor: Tom Preston-Werner <tom@mojombo.com>Date: Fri Nov 7 13:47:59 2008 -0500ignore *.gem

You can also combine these syntaxes – you can get the second parent of the previous reference (assuming it was a merge commit) by using HEAD~3^2, and so on.

Commit Ranges

Now that you can specify individual commits, let’s see how to specify ranges of commits. This is particularly useful for managing your branches – if you have a lot of branches, you can use range specifications to answer questions such as, “What work is on this branch that I haven’t yet merged into my main branch?”

Double Dot

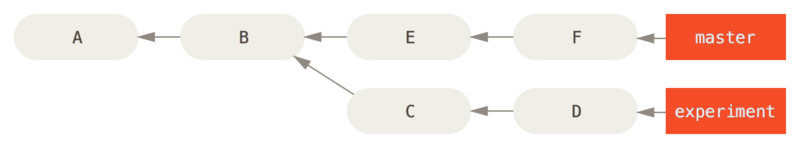

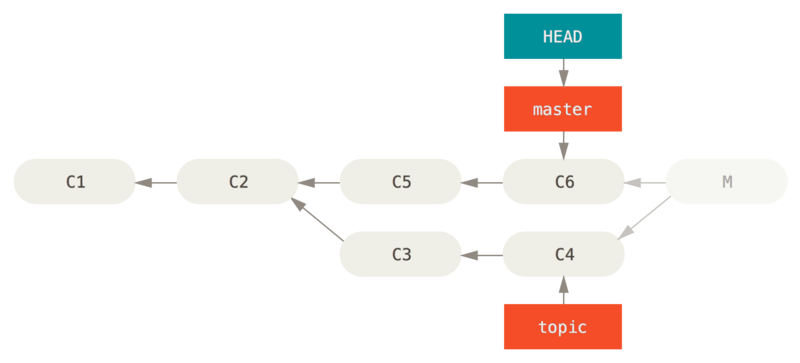

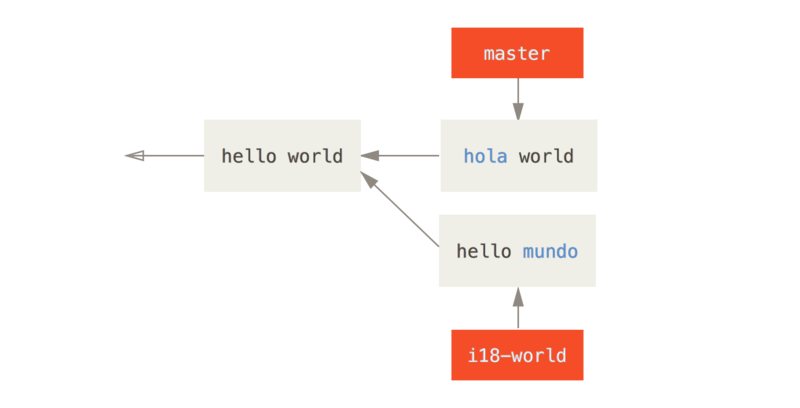

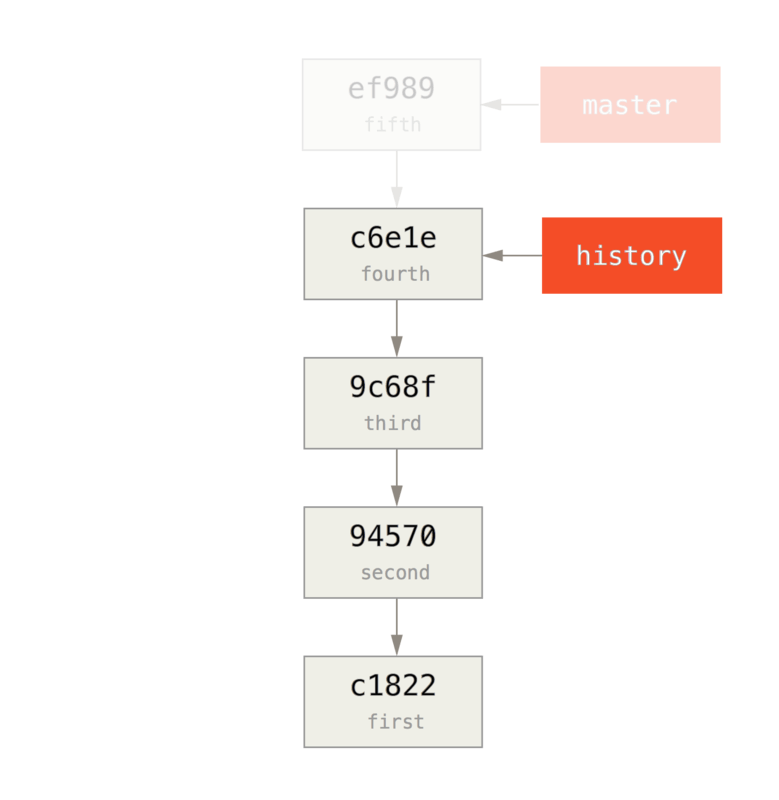

The most common range specification is the double-dot syntax. This basically asks Git to resolve a range of commits that are reachable from one commit but aren’t reachable from another. For example, say you have a commit history that looks like Figure 7-1.

You want to see what is in your experiment branch that hasn’t yet been merged into your master branch.

You can ask Git to show you a log of just those commits with master..experiment – that means “all commits reachable by experiment that aren’t reachable by master.”

For the sake of brevity and clarity in these examples, I’ll use the letters of the commit objects from the diagram in place of the actual log output in the order that they would display:

$git log master..experimentDC

If, on the other hand, you want to see the opposite – all commits in master that aren’t in experiment – you can reverse the branch names.

experiment..master shows you everything in master not reachable from experiment:

$git log experiment..masterFE

This is useful if you want to keep the experiment branch up to date and preview what you’re about to merge in.

Another very frequent use of this syntax is to see what you’re about to push to a remote:

$ git log origin/master..HEADThis command shows you any commits in your current branch that aren’t in the master branch on your origin remote.

If you run a git push and your current branch is tracking origin/master, the commits listed by git log origin/master..HEAD are the commits that will be transferred to the server.

You can also leave off one side of the syntax to have Git assume HEAD.

For example, you can get the same results as in the previous example by typing git log origin/master.. – Git substitutes HEAD if one side is missing.

Multiple Points

The double-dot syntax is useful as a shorthand; but perhaps you want to specify more than two branches to indicate your revision, such as seeing what commits are in any of several branches that aren’t in the branch you’re currently on.

Git allows you to do this by using either the ^ character or --not before any reference from which you don’t want to see reachable commits.

Thus these three commands are equivalent:

$git log refA..refB$git log ^refA refB$git log refB --not refA

This is nice because with this syntax you can specify more than two references in your query, which you cannot do with the double-dot syntax.

For instance, if you want to see all commits that are reachable from refA or refB but not from refC, you can type one of these:

$git log refA refB ^refC$git log refA refB --not refC

This makes for a very powerful revision query system that should help you figure out what is in your branches.

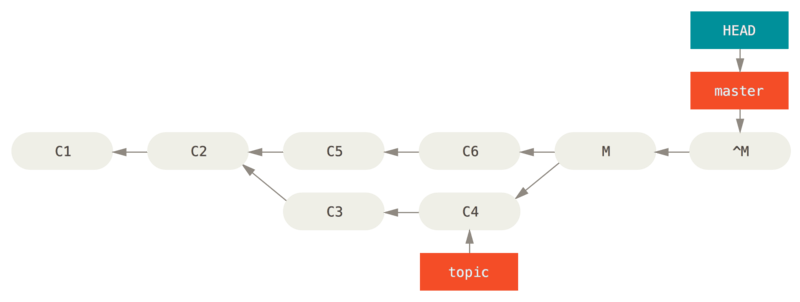

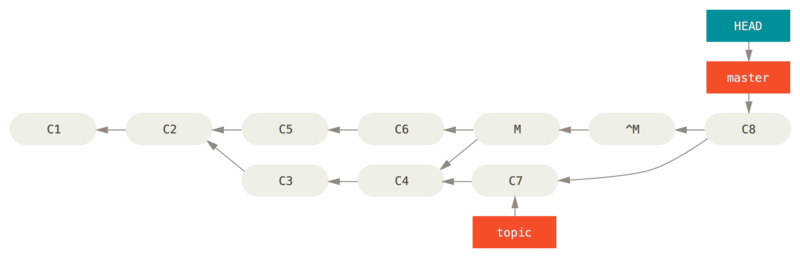

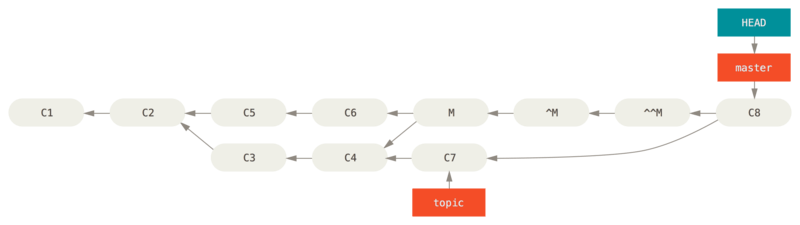

Triple Dot

The last major range-selection syntax is the triple-dot syntax, which specifies all the commits that are reachable by either of two references but not by both of them.

Look back at the example commit history in Figure 7-1.

If you want to see what is in master or experiment but not any common references, you can run

$git log master...experimentFEDC

Again, this gives you normal log output but shows you only the commit information for those four commits, appearing in the traditional commit date ordering.

A common switch to use with the log command in this case is --left-right, which shows you which side of the range each commit is in.

This helps make the data more useful:

$git log --left-right master...experiment< F< E> D> C

With these tools, you can much more easily let Git know what commit or commits you want to inspect.

Interactive Staging

Git comes with a couple of scripts that make some command-line tasks easier.

Here, you’ll look at a few interactive commands that can help you easily craft your commits to include only certain combinations and parts of files.

These tools are very helpful if you modify a bunch of files and then decide that you want those changes to be in several focused commits rather than one big messy commit.

This way, you can make sure your commits are logically separate changesets and can be easily reviewed by the developers working with you.

If you run git add with the -i or --interactive option, Git goes into an interactive shell mode, displaying something like this:

$git add -istaged unstaged path1: unchanged +0/-1 TODO2: unchanged +1/-1 index.html3: unchanged +5/-1 lib/simplegit.rb*** Commands ***1: status 2: update 3: revert 4: add untracked5: patch 6: diff 7: quit 8: helpWhat now>

You can see that this command shows you a much different view of your staging area – basically the same information you get with git status but a bit more succinct and informative.

It lists the changes you’ve staged on the left and unstaged changes on the right.

After this comes a Commands section. Here you can do a number of things, including staging files, unstaging files, staging parts of files, adding untracked files, and seeing diffs of what has been staged.

Staging and Unstaging Files

If you type 2 or u at the What now> prompt, the script prompts you for which files you want to stage:

What now> 2staged unstaged path1: unchanged +0/-1 TODO2: unchanged +1/-1 index.html3: unchanged +5/-1 lib/simplegit.rbUpdate>>

To stage the TODO and index.html files, you can type the numbers:

Update>> 1,2staged unstaged path* 1: unchanged +0/-1 TODO* 2: unchanged +1/-1 index.html3: unchanged +5/-1 lib/simplegit.rbUpdate>>

The * next to each file means the file is selected to be staged.

If you press Enter after typing nothing at the Update>> prompt, Git takes anything selected and stages it for you:

Update>>updated 2 paths*** Commands ***1: status 2: update 3: revert 4: add untracked5: patch 6: diff 7: quit 8: helpWhat now> 1staged unstaged path1: +0/-1 nothing TODO2: +1/-1 nothing index.html3: unchanged +5/-1 lib/simplegit.rb

Now you can see that the TODO and index.html files are staged and the simplegit.rb file is still unstaged.

If you want to unstage the TODO file at this point, you use the 3 or r (for revert) option:

*** Commands ***1: status 2: update 3: revert 4: add untracked5: patch 6: diff 7: quit 8: helpWhat now> 3staged unstaged path1: +0/-1 nothing TODO2: +1/-1 nothing index.html3: unchanged +5/-1 lib/simplegit.rbRevert>> 1staged unstaged path* 1: +0/-1 nothing TODO2: +1/-1 nothing index.html3: unchanged +5/-1 lib/simplegit.rbRevert>> [enter]reverted one path

Looking at your Git status again, you can see that you’ve unstaged the TODO file:

*** Commands ***1: status 2: update 3: revert 4: add untracked5: patch 6: diff 7: quit 8: helpWhat now> 1staged unstaged path1: unchanged +0/-1 TODO2: +1/-1 nothing index.html3: unchanged +5/-1 lib/simplegit.rb

To see the diff of what you’ve staged, you can use the 6 or d (for diff) command.

It shows you a list of your staged files, and you can select the ones for which you would like to see the staged diff.

This is much like specifying git diff --cached on the command line:

*** Commands ***1: status 2: update 3: revert 4: add untracked5: patch 6: diff 7: quit 8: helpWhat now> 6staged unstaged path1: +1/-1 nothing index.htmlReview diff>> 1diff --git a/index.html b/index.htmlindex 4d07108..4335f49 100644--- a/index.html+++ b/index.html@@ -16,7 +16,7 @@ Date Finder<p id="out">...</p>-<div id="footer">contact : support@github.com</div>+<div id="footer">contact : email.support@github.com</div><script type="text/javascript">

With these basic commands, you can use the interactive add mode to deal with your staging area a little more easily.

Staging Patches

It’s also possible for Git to stage certain parts of files and not the rest.

For example, if you make two changes to your simplegit.rb file and want to stage one of them and not the other, doing so is very easy in Git.

From the interactive prompt, type 5 or p (for patch).

Git will ask you which files you would like to partially stage; then, for each section of the selected files, it will display hunks of the file diff and ask if you would like to stage them, one by one:

diff --git a/lib/simplegit.rb b/lib/simplegit.rbindex dd5ecc4..57399e0 100644--- a/lib/simplegit.rb+++ b/lib/simplegit.rb@@ -22,7 +22,7 @@ class SimpleGitenddef log(treeish = 'master')- command("git log -n 25 #{treeish}")+ command("git log -n 30 #{treeish}")enddef blame(path)Stage this hunk [y,n,a,d,/,j,J,g,e,?]?

You have a lot of options at this point.

Typing ? shows a list of what you can do:

Stage this hunk [y,n,a,d,/,j,J,g,e,?]? ?y - stage this hunkn - do not stage this hunka - stage this and all the remaining hunks in the filed - do not stage this hunk nor any of the remaining hunks in the fileg - select a hunk to go to/ - search for a hunk matching the given regexj - leave this hunk undecided, see next undecided hunkJ - leave this hunk undecided, see next hunkk - leave this hunk undecided, see previous undecided hunkK - leave this hunk undecided, see previous hunks - split the current hunk into smaller hunkse - manually edit the current hunk? - print help

Generally, you’ll type y or n if you want to stage each hunk, but staging all of them in certain files or skipping a hunk decision until later can be helpful too.

If you stage one part of the file and leave another part unstaged, your status output will look like this:

What now> 1staged unstaged path1: unchanged +0/-1 TODO2: +1/-1 nothing index.html3: +1/-1 +4/-0 lib/simplegit.rb

The status of the simplegit.rb file is interesting.

It shows you that a couple of lines are staged and a couple are unstaged.

You’ve partially staged this file.

At this point, you can exit the interactive adding script and run git commit to commit the partially staged files.

You also don’t need to be in interactive add mode to do the partial-file staging – you can start the same script by using git add -p or git add --patch on the command line.

Furthermore, you can use patch mode for partially resetting files with the reset --patch command, for checking out parts of files with the checkout --patch command and for stashing parts of files with the stash save --patch command.

We’ll go into more details on each of these as we get to more advanced usages of these commands.

Stashing and Cleaning

Often, when you’ve been working on part of your project, things are in a messy state and you want to switch branches for a bit to work on something else.

The problem is, you don’t want to do a commit of half-done work just so you can get back to this point later.

The answer to this issue is the git stash command.

Stashing takes the dirty state of your working directory – that is, your modified tracked files and staged changes – and saves it on a stack of unfinished changes that you can reapply at any time.

Stashing Your Work

To demonstrate, you’ll go into your project and start working on a couple of files and possibly stage one of the changes.

If you run git status, you can see your dirty state:

$git statusChanges to be committed:(use "git reset HEAD <file>..." to unstage)modified: index.htmlChanges not staged for commit:(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)(use "git checkout -- <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)modified: lib/simplegit.rb

Now you want to switch branches, but you don’t want to commit what you’ve been working on yet; so you’ll stash the changes.

To push a new stash onto your stack, run git stash or git stash save:

$git stashSaved working directory and index state \"WIP on master: 049d078 added the index file"HEAD is now at 049d078 added the index file(To restore them type "git stash apply")

Your working directory is clean:

$git status#On branch masternothing to commit, working directory clean

At this point, you can easily switch branches and do work elsewhere; your changes are stored on your stack.

To see which stashes you’ve stored, you can use git stash list:

$git stash liststash@{0}: WIP on master: 049d078 added the index filestash@{1}: WIP on master: c264051 Revert "added file_size"stash@{2}: WIP on master: 21d80a5 added number to log

In this case, two stashes were done previously, so you have access to three different stashed works.

You can reapply the one you just stashed by using the command shown in the help output of the original stash command: git stash apply.

If you want to apply one of the older stashes, you can specify it by naming it, like this: git stash apply stash@{2}.

If you don’t specify a stash, Git assumes the most recent stash and tries to apply it:

$git stash applyOn branch masterChanges not staged for commit:(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)(use "git checkout -- <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)modified: index.htmlmodified: lib/simplegit.rbno changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")

You can see that Git re-modifies the files you reverted when you saved the stash. In this case, you had a clean working directory when you tried to apply the stash, and you tried to apply it on the same branch you saved it from; but having a clean working directory and applying it on the same branch aren’t necessary to successfully apply a stash. You can save a stash on one branch, switch to another branch later, and try to reapply the changes. You can also have modified and uncommitted files in your working directory when you apply a stash – Git gives you merge conflicts if anything no longer applies cleanly.

The changes to your files were reapplied, but the file you staged before wasn’t restaged.

To do that, you must run the git stash apply command with a --index option to tell the command to try to reapply the staged changes.

If you had run that instead, you’d have gotten back to your original position:

$git stash apply --indexOn branch masterChanges to be committed:(use "git reset HEAD <file>..." to unstage)modified: index.htmlChanges not staged for commit:(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)(use "git checkout -- <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)modified: lib/simplegit.rb

The apply option only tries to apply the stashed work – you continue to have it on your stack.

To remove it, you can run git stash drop with the name of the stash to remove:

$git stash liststash@{0}: WIP on master: 049d078 added the index filestash@{1}: WIP on master: c264051 Revert "added file_size"stash@{2}: WIP on master: 21d80a5 added number to log$git stash drop stash@{0}Dropped stash@{0} (364e91f3f268f0900bc3ee613f9f733e82aaed43)

You can also run git stash pop to apply the stash and then immediately drop it from your stack.

Creative Stashing

There are a few stash variants that may also be helpful.

The first option that is quite popular is the --keep-index option to the stash save command.

This tells Git to not stash anything that you’ve already staged with the git add command.

This can be really helpful if you’ve made a number of changes but want to only commit some of them and then come back to the rest of the changes at a later time.

$git status -sM index.htmlM lib/simplegit.rb$git stash --keep-indexSaved working directory and index state WIP on master: 1b65b17 added the index fileHEAD is now at 1b65b17 added the index file$git status -sM index.html

Another common thing you may want to do with stash is to stash the untracked files as well as the tracked ones.

By default, git stash will only store files that are already in the index.

If you specify --include-untracked or -u, Git will also stash any untracked files you have created.

$git status -sM index.htmlM lib/simplegit.rb?? new-file.txt$git stash -uSaved working directory and index state WIP on master: 1b65b17 added the index fileHEAD is now at 1b65b17 added the index file$git status -s$

Finally, if you specify the --patch flag, Git will not stash everything that is modified but will instead prompt you interactively which of the changes you would like to stash and which you would like to keep in your working directory.

$git stash --patchdiff --git a/lib/simplegit.rb b/lib/simplegit.rbindex 66d332e..8bb5674 100644--- a/lib/simplegit.rb+++ b/lib/simplegit.rb@@ -16,6 +16,10 @@ class SimpleGitreturn `#{git_cmd} 2>&1`.chompendend++ def show(treeish = 'master')+ command("git show #{treeish}")+ endendtestStash this hunk [y,n,q,a,d,/,e,?]? ySaved working directory and index state WIP on master: 1b65b17 added the index file

Creating a Branch from a Stash

If you stash some work, leave it there for a while, and continue on the branch from which you stashed the work, you may have a problem reapplying the work.

If the apply tries to modify a file that you’ve since modified, you’ll get a merge conflict and will have to try to resolve it.

If you want an easier way to test the stashed changes again, you can run git stash branch, which creates a new branch for you, checks out the commit you were on when you stashed your work, reapplies your work there, and then drops the stash if it applies successfully:

$git stash branch testchangesM index.htmlM lib/simplegit.rbSwitched to a new branch 'testchanges'On branch testchangesChanges to be committed:(use "git reset HEAD <file>..." to unstage)modified: index.htmlChanges not staged for commit:(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)(use "git checkout -- <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)modified: lib/simplegit.rbDropped refs/stash@{0} (29d385a81d163dfd45a452a2ce816487a6b8b014)

This is a nice shortcut to recover stashed work easily and work on it in a new branch.

Cleaning your Working Directory

Finally, you may not want to stash some work or files in your working directory, but simply get rid of them.

The git clean command will do this for you.

Some common reasons for this might be to remove cruft that has been generated by merges or external tools or to remove build artifacts in order to run a clean build.

You’ll want to be pretty careful with this command, since it’s designed to remove files from your working directory that are not tracked.

If you change your mind, there is often no retrieving the content of those files.

A safer option is to run git stash --all to remove everything but save it in a stash.

Assuming you do want to remove cruft files or clean your working directory, you can do so with git clean.

To remove all the untracked files in your working directory, you can run git clean -f -d, which removes any files and also any subdirectories that become empty as a result.

The -f means force or "really do this".

If you ever want to see what it would do, you can run the command with the -n option, which means “do a dry run and tell me what you would have removed”.

$git clean -d -nWould remove test.oWould remove tmp/

By default, the git clean command will only remove untracked files that are not ignored.

Any file that matches a pattern in your .gitignore or other ignore files will not be removed.

If you want to remove those files too, such as to remove all .o files generated from a build so you can do a fully clean build, you can add a -x to the clean command.

$git status -sM lib/simplegit.rb?? build.TMP?? tmp/$git clean -n -dWould remove build.TMPWould remove tmp/$git clean -n -d -xWould remove build.TMPWould remove test.oWould remove tmp/

If you don’t know what the git clean command is going to do, always run it with a -n first to double check before changing the -n to a -f and doing it for real.

The other way you can be careful about the process is to run it with the -i or “interactive” flag.

This will run the clean command in an interactive mode.

$git clean -x -iWould remove the following items:build.TMP test.o*** Commands ***1: clean 2: filter by pattern 3: select by numbers 4: ask each 5: quit6: helpWhat now>

This way you can step through each file individually or specify patterns for deletion interactively.

Signing Your Work

Git is cryptographically secure, but it’s not foolproof. If you’re taking work from others on the internet and want to verify that commits are actually from a trusted source, Git has a few ways to sign and verify work using GPG.

GPG Introduction

First of all, if you want to sign anything you need to get GPG configured and your personal key installed.

$gpg --list-keys/Users/schacon/.gnupg/pubring.gpg---------------------------------pub 2048R/0A46826A 2014-06-04uid Scott Chacon (Git signing key) <schacon@gmail.com>sub 2048R/874529A9 2014-06-04

If you don’t have a key installed, you can generate one with gpg --gen-key.

gpg --gen-keyOnce you have a private key to sign with, you can configure Git to use it for signing things by setting the user.signingkey config setting.

git config --global user.signingkey 0A46826ANow Git will use your key by default to sign tags and commits if you want.

Signing Commits

In more recent versions of Git (v1.7.9 and above), you can now also sign individual commits.

If you’re interested in signing commits directly instead of just the tags, all you need to do is add a -S to your git commit command.

$git commit -a -S -m'signed commit'You need a passphrase to unlock the secret key foruser: "Scott Chacon (Git signing key) <schacon@gmail.com>"2048-bit RSA key, ID 0A46826A, created 2014-06-04[master 5c3386c] signed commit4 files changed, 4 insertions(+), 24 deletions(-)rewrite Rakefile (100%)create mode 100644 lib/git.rb

To see and verify these signatures, there is also a --show-signature option to git log.

$git log --show-signature -1commit 5c3386cf54bba0a33a32da706aa52bc0155503c2gpg: Signature made Wed Jun 4 19:49:17 2014 PDT using RSA key ID 0A46826Agpg: Good signature from "Scott Chacon (Git signing key) <schacon@gmail.com>"Author: Scott Chacon <schacon@gmail.com>Date: Wed Jun 4 19:49:17 2014 -0700signed commit

Additionally, you can configure git log to check any signatures it finds and list them in its output with the %G? format.

$git log --pretty="format:%h %G? %aN %s"5c3386c G Scott Chacon signed commitca82a6d N Scott Chacon changed the version number085bb3b N Scott Chacon removed unnecessary test codea11bef0 N Scott Chacon first commit

Here we can see that only the latest commit is signed and valid and the previous commits are not.

In Git 1.8.3 and later, "git merge" and "git pull" can be told to inspect and reject when merging a commit that does not carry a trusted GPG signature with the --verify-signatures command.

If you use this option when merging a branch and it contains commits that are not signed and valid, the merge will not work.

$git merge --verify-signatures non-verifyfatal: Commit ab06180 does not have a GPG signature.

If the merge contains only valid signed commits, the merge command will show you all the signatures it has checked and then move forward with the merge.

$git merge --verify-signatures signed-branchCommit 13ad65e has a good GPG signature by Scott Chacon (Git signing key) <schacon@gmail.com>Updating 5c3386c..13ad65eFast-forwardREADME | 2 ++1 file changed, 2 insertions(+)

You can also use the -S option with the git merge command itself to sign the resulting merge commit itself.

The following example both verifies that every commit in the branch to be merged is signed and furthermore signs the resulting merge commit.

$git merge --verify-signatures -S signed-branchCommit 13ad65e has a good GPG signature by Scott Chacon (Git signing key) <schacon@gmail.com>You need a passphrase to unlock the secret key foruser: "Scott Chacon (Git signing key) <schacon@gmail.com>"2048-bit RSA key, ID 0A46826A, created 2014-06-04Merge made by the 'recursive' strategy.README | 2 ++1 file changed, 2 insertions(+)

Everyone Must Sign

Signing tags and commits is great, but if you decide to use this in your normal workflow, you’ll have to make sure that everyone on your team understands how to do so. If you don’t, you’ll end up spending a lot of time helping people figure out how to rewrite their commits with signed versions. Make sure you understand GPG and the benefits of signing things before adopting this as part of your standard workflow.

Searching

With just about any size codebase, you’ll often need to find where a function is called or defined, or find the history of a method. Git provides a couple of useful tools for looking through the code and commits stored in its database quickly and easily. We’ll go through a few of them.

Git Grep

Git ships with a command called grep that allows you to easily search through any committed tree or the working directory for a string or regular expression.

For these examples, we’ll look through the Git source code itself.

By default, it will look through the files in your working directory.

You can pass -n to print out the line numbers where Git has found matches.

$git grep -n gmtime_rcompat/gmtime.c:3:#undef gmtime_rcompat/gmtime.c:8: return git_gmtime_r(timep, &result);compat/gmtime.c:11:struct tm *git_gmtime_r(const time_t *timep, struct tm *result)compat/gmtime.c:16: ret = gmtime_r(timep, result);compat/mingw.c:606:struct tm *gmtime_r(const time_t *timep, struct tm *result)compat/mingw.h:162:struct tm *gmtime_r(const time_t *timep, struct tm *result);date.c:429: if (gmtime_r(&now, &now_tm))date.c:492: if (gmtime_r(&time, tm)) {git-compat-util.h:721:struct tm *git_gmtime_r(const time_t *, struct tm *);git-compat-util.h:723:#define gmtime_r git_gmtime_r

There are a number of interesting options you can provide the grep command.

For instance, instead of the previous call, you can have Git summarize the output by just showing you which files matched and how many matches there were in each file with the --count option:

$git grep --count gmtime_rcompat/gmtime.c:4compat/mingw.c:1compat/mingw.h:1date.c:2git-compat-util.h:2

If you want to see what method or function it thinks it has found a match in, you can pass -p:

$git grep -p gmtime_r *.cdate.c=static int match_multi_number(unsigned long num, char c, const char *date, char *end, struct tm *tm)date.c: if (gmtime_r(&now, &now_tm))date.c=static int match_digit(const char *date, struct tm *tm, int *offset, int *tm_gmt)date.c: if (gmtime_r(&time, tm)) {

So here we can see that gmtime_r is called in the match_multi_number and match_digit functions in the date.c file.

You can also look for complex combinations of strings with the --and flag, which makes sure that multiple matches are in the same line.

For instance, let’s look for any lines that define a constant with either the strings “LINK” or “BUF_MAX” in them in the Git codebase in an older 1.8.0 version.

Here we’ll also use the --break and --heading options which help split up the output into a more readable format.

$git grep --break --heading\-n -e '#define' --and \( -e LINK -e BUF_MAX \) v1.8.0v1.8.0:builtin/index-pack.c62:#define FLAG_LINK (1u<<20)v1.8.0:cache.h73:#define S_IFGITLINK 016000074:#define S_ISGITLINK(m) (((m) & S_IFMT) == S_IFGITLINK)v1.8.0:environment.c54:#define OBJECT_CREATION_MODE OBJECT_CREATION_USES_HARDLINKSv1.8.0:strbuf.c326:#define STRBUF_MAXLINK (2*PATH_MAX)v1.8.0:symlinks.c53:#define FL_SYMLINK (1 << 2)v1.8.0:zlib.c30:/* #define ZLIB_BUF_MAX ((uInt)-1) */31:#define ZLIB_BUF_MAX ((uInt) 1024 * 1024 * 1024) /* 1GB */

The git grep command has a few advantages over normal searching commands like grep and ack.

The first is that it’s really fast, the second is that you can search through any tree in Git, not just the working directory.

As we saw in the above example, we looked for terms in an older version of the Git source code, not the version that was currently checked out.

Git Log Searching

Perhaps you’re looking not for where a term exists, but when it existed or was introduced.

The git log command has a number of powerful tools for finding specific commits by the content of their messages or even the content of the diff they introduce.

If we want to find out for example when the ZLIB_BUF_MAX constant was originally introduced, we can tell Git to only show us the commits that either added or removed that string with the -S option.

$git log -SZLIB_BUF_MAX --onelinee01503b zlib: allow feeding more than 4GB in one goef49a7a zlib: zlib can only process 4GB at a time

If we look at the diff of those commits we can see that in ef49a7a the constant was introduced and in e01503b it was modified.

If you need to be more specific, you can provide a regular expression to search for with the -G option.

Line Log Search

Another fairly advanced log search that is insanely useful is the line history search.

This is a fairly recent addition and not very well known, but it can be really helpful.

It is called with the -L option to git log and will show you the history of a function or line of code in your codebase.

For example, if we wanted to see every change made to the function git_deflate_bound in the zlib.c file, we could run git log -L :git_deflate_bound:zlib.c.

This will try to figure out what the bounds of that function are and then look through the history and show us every change that was made to the function as a series of patches back to when the function was first created.

$git log -L :git_deflate_bound:zlib.ccommit ef49a7a0126d64359c974b4b3b71d7ad42ee3bcaAuthor: Junio C Hamano <gitster@pobox.com>Date: Fri Jun 10 11:52:15 2011 -0700zlib: zlib can only process 4GB at a timediff --git a/zlib.c b/zlib.c--- a/zlib.c+++ b/zlib.c@@ -85,5 +130,5 @@-unsigned long git_deflate_bound(z_streamp strm, unsigned long size)+unsigned long git_deflate_bound(git_zstream *strm, unsigned long size){- return deflateBound(strm, size);+ return deflateBound(&strm->z, size);}commit 225a6f1068f71723a910e8565db4e252b3ca21faAuthor: Junio C Hamano <gitster@pobox.com>Date: Fri Jun 10 11:18:17 2011 -0700zlib: wrap deflateBound() toodiff --git a/zlib.c b/zlib.c--- a/zlib.c+++ b/zlib.c@@ -81,0 +85,5 @@+unsigned long git_deflate_bound(z_streamp strm, unsigned long size)+{+ return deflateBound(strm, size);+}+

If Git can’t figure out how to match a function or method in your programming language, you can also provide it a regex.

For example, this would have done the same thing: git log -L '/unsigned long git_deflate_bound/',/^}/:zlib.c.

You could also give it a range of lines or a single line number and you’ll get the same sort of output.

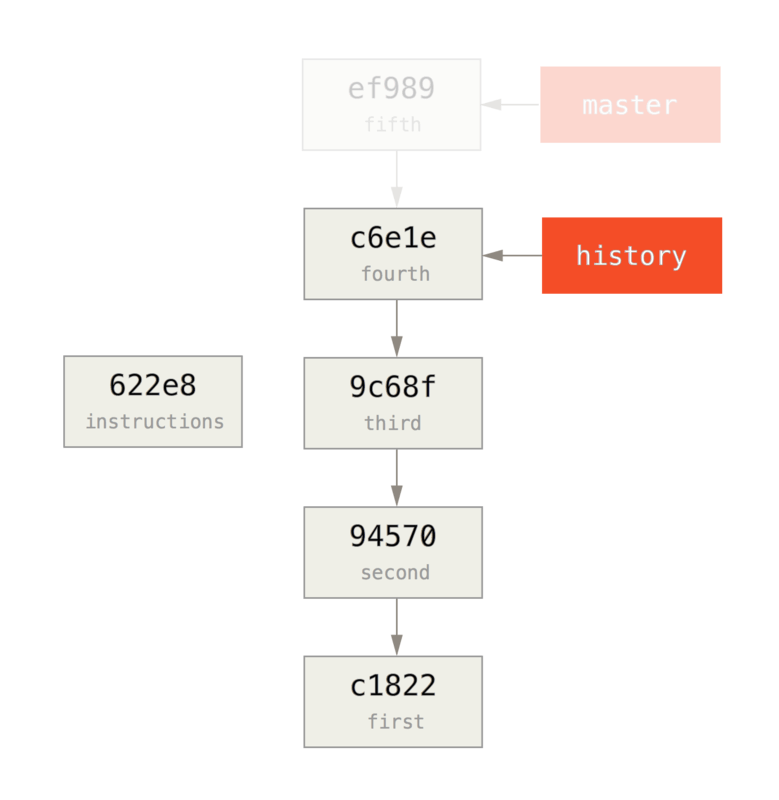

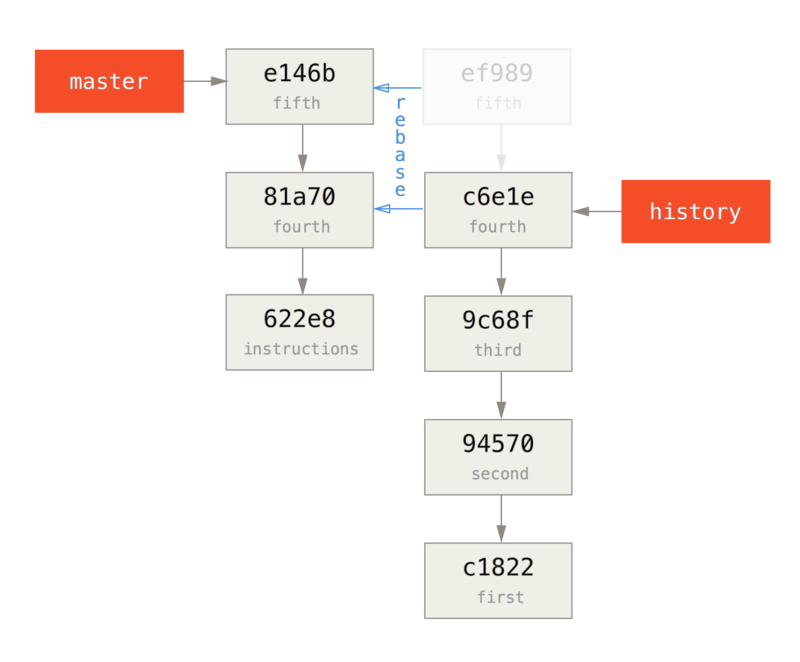

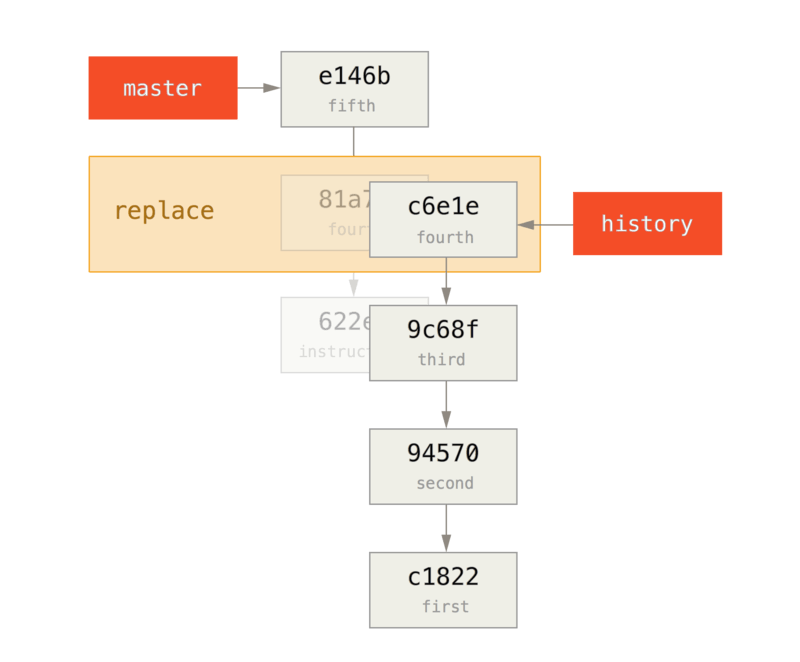

Rewriting History

Many times, when working with Git, you may want to revise your commit history for some reason. One of the great things about Git is that it allows you to make decisions at the last possible moment. You can decide what files go into which commits right before you commit with the staging area, you can decide that you didn’t mean to be working on something yet with the stash command, and you can rewrite commits that already happened so they look like they happened in a different way. This can involve changing the order of the commits, changing messages or modifying files in a commit, squashing together or splitting apart commits, or removing commits entirely – all before you share your work with others.

In this section, you’ll cover how to accomplish these very useful tasks so that you can make your commit history look the way you want before you share it with others.

Changing the Last Commit

Changing your last commit is probably the most common rewriting of history that you’ll do. You’ll often want to do two basic things to your last commit: change the commit message, or change the snapshot you just recorded by adding, changing and removing files.

If you only want to modify your last commit message, it’s very simple:

$ git commit --amendThat drops you into your text editor, which has your last commit message in it, ready for you to modify the message. When you save and close the editor, the editor writes a new commit containing that message and makes it your new last commit.

If you’ve committed and then you want to change the snapshot you committed by adding or changing files, possibly because you forgot to add a newly created file when you originally committed, the process works basically the same way.

You stage the changes you want by editing a file and running git add on it or git rm to a tracked file, and the subsequent git commit --amend takes your current staging area and makes it the snapshot for the new commit.

You need to be careful with this technique because amending changes the SHA-1 of the commit. It’s like a very small rebase – don’t amend your last commit if you’ve already pushed it.

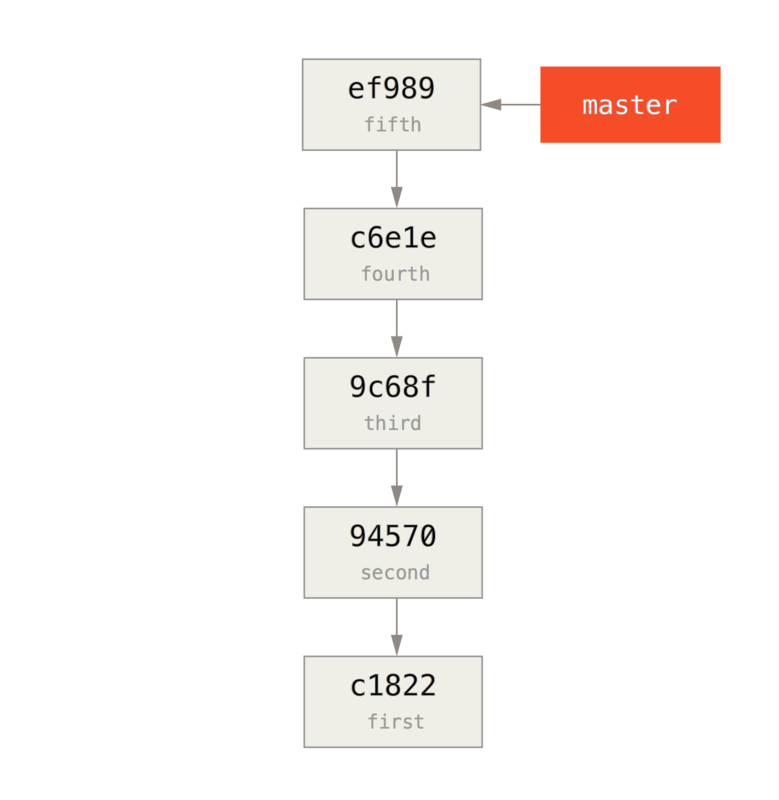

Changing Multiple Commit Messages

To modify a commit that is farther back in your history, you must move to more complex tools.

Git doesn’t have a modify-history tool, but you can use the rebase tool to rebase a series of commits onto the HEAD they were originally based on instead of moving them to another one.

With the interactive rebase tool, you can then stop after each commit you want to modify and change the message, add files, or do whatever you wish.

You can run rebase interactively by adding the -i option to git rebase.

You must indicate how far back you want to rewrite commits by telling the command which commit to rebase onto.

For example, if you want to change the last three commit messages, or any of the commit messages in that group, you supply as an argument to git rebase -i the parent of the last commit you want to edit, which is HEAD~2^ or HEAD~3.

It may be easier to remember the ~3 because you’re trying to edit the last three commits; but keep in mind that you’re actually designating four commits ago, the parent of the last commit you want to edit:

$ git rebase -i HEAD~3Remember again that this is a rebasing command – every commit included in the range HEAD~3..HEAD will be rewritten, whether you change the message or not.

Don’t include any commit you’ve already pushed to a central server – doing so will confuse other developers by providing an alternate version of the same change.

Running this command gives you a list of commits in your text editor that looks something like this:

pick f7f3f6d changed my name a bitpick 310154e updated README formatting and added blamepick a5f4a0d added cat-file#Rebase 710f0f8..a5f4a0d onto 710f0f8##Commands:#p,pick=use commit#r,reword=use commit, but edit the commit message#e,edit=use commit, but stopforamending#s,squash=use commit, but meld into previous commit#f,fixup=like"squash", but discard this commit's log message#x,exec=runcommand(the rest of the line)using shell##These lines can be re-ordered;they are executed from top to bottom.##If you remove a line here THAT COMMIT WILL BE LOST.##However,ifyou remove everything, the rebase will be aborted.##Note that empty commits are commented out

It’s important to note that these commits are listed in the opposite order than you normally see them using the log command.

If you run a log, you see something like this:

$git log --pretty=format:"%h %s"HEAD~3..HEADa5f4a0d added cat-file310154e updated README formatting and added blamef7f3f6d changed my name a bit

Notice the reverse order.

The interactive rebase gives you a script that it’s going to run.

It will start at the commit you specify on the command line (HEAD~3) and replay the changes introduced in each of these commits from top to bottom.

It lists the oldest at the top, rather than the newest, because that’s the first one it will replay.

You need to edit the script so that it stops at the commit you want to edit. To do so, change the word ‘pick’ to the word ‘edit’ for each of the commits you want the script to stop after. For example, to modify only the third commit message, you change the file to look like this:

edit f7f3f6d changed my name a bitpick 310154e updated README formatting and added blamepick a5f4a0d added cat-file

When you save and exit the editor, Git rewinds you back to the last commit in that list and drops you on the command line with the following message:

$git rebase -i HEAD~3Stopped at f7f3f6d... changed my name a bitYou can amend the commit now, withgit commit --amendOnce you’re satisfied with your changes, rungit rebase --continue

These instructions tell you exactly what to do. Type

$ git commit --amendChange the commit message, and exit the editor. Then, run

$ git rebase --continueThis command will apply the other two commits automatically, and then you’re done. If you change pick to edit on more lines, you can repeat these steps for each commit you change to edit. Each time, Git will stop, let you amend the commit, and continue when you’re finished.

Reordering Commits

You can also use interactive rebases to reorder or remove commits entirely. If you want to remove the “added cat-file” commit and change the order in which the other two commits are introduced, you can change the rebase script from this

pick f7f3f6d changed my name a bitpick 310154e updated README formatting and added blamepick a5f4a0d added cat-file

to this:

pick 310154e updated README formatting and added blamepick f7f3f6d changed my name a bit

When you save and exit the editor, Git rewinds your branch to the parent of these commits, applies 310154e and then f7f3f6d, and then stops.

You effectively change the order of those commits and remove the “added cat-file” commit completely.

Squashing Commits

It’s also possible to take a series of commits and squash them down into a single commit with the interactive rebasing tool. The script puts helpful instructions in the rebase message:

##Commands:#p,pick=use commit#r,reword=use commit, but edit the commit message#e,edit=use commit, but stopforamending#s,squash=use commit, but meld into previous commit#f,fixup=like"squash", but discard this commit's log message#x,exec=runcommand(the rest of the line)using shell##These lines can be re-ordered;they are executed from top to bottom.##If you remove a line here THAT COMMIT WILL BE LOST.##However,ifyou remove everything, the rebase will be aborted.##Note that empty commits are commented out

If, instead of “pick” or “edit”, you specify “squash”, Git applies both that change and the change directly before it and makes you merge the commit messages together. So, if you want to make a single commit from these three commits, you make the script look like this:

pick f7f3f6d changed my name a bitsquash 310154e updated README formatting and added blamesquash a5f4a0d added cat-file

When you save and exit the editor, Git applies all three changes and then puts you back into the editor to merge the three commit messages:

#This is a combination of3commits.#The first commit's message is:changed my name a bit#This is the 2nd commit message:updated README formatting and added blame#This is the 3rd commit message:added cat-file

When you save that, you have a single commit that introduces the changes of all three previous commits.

Splitting a Commit

Splitting a commit undoes a commit and then partially stages and commits as many times as commits you want to end up with.

For example, suppose you want to split the middle commit of your three commits.

Instead of “updated README formatting and added blame”, you want to split it into two commits: “updated README formatting” for the first, and “added blame” for the second.

You can do that in the rebase -i script by changing the instruction on the commit you want to split to “edit”:

pick f7f3f6d changed my name a bitedit 310154e updated README formatting and added blamepick a5f4a0d added cat-file

Then, when the script drops you to the command line, you reset that commit, take the changes that have been reset, and create multiple commits out of them.

When you save and exit the editor, Git rewinds to the parent of the first commit in your list, applies the first commit (f7f3f6d), applies the second (310154e), and drops you to the console.

There, you can do a mixed reset of that commit with git reset HEAD^, which effectively undoes that commit and leaves the modified files unstaged.

Now you can stage and commit files until you have several commits, and run git rebase --continue when you’re done:

$git reset HEAD^$git add README$git commit -m'updated README formatting'$git add lib/simplegit.rb$git commit -m'added blame'$git rebase --continue

Git applies the last commit (a5f4a0d) in the script, and your history looks like this:

$git log -4 --pretty=format:"%h %s"1c002dd added cat-file9b29157 added blame35cfb2b updated README formattingf3cc40e changed my name a bit

Once again, this changes the SHA-1s of all the commits in your list, so make sure no commit shows up in that list that you’ve already pushed to a shared repository.

The Nuclear Option: filter-branch

There is another history-rewriting option that you can use if you need to rewrite a larger number of commits in some scriptable way – for instance, changing your email address globally or removing a file from every commit.

The command is filter-branch, and it can rewrite huge swaths of your history, so you probably shouldn’t use it unless your project isn’t yet public and other people haven’t based work off the commits you’re about to rewrite.

However, it can be very useful.

You’ll learn a few of the common uses so you can get an idea of some of the things it’s capable of.

Removing a File from Every Commit

This occurs fairly commonly.

Someone accidentally commits a huge binary file with a thoughtless git add ., and you want to remove it everywhere.

Perhaps you accidentally committed a file that contained a password, and you want to make your project open source.

filter-branch is the tool you probably want to use to scrub your entire history.

To remove a file named passwords.txt from your entire history, you can use the --tree-filter option to filter-branch:

$git filter-branch --tree-filter'rm -f passwords.txt'HEADRewrite 6b9b3cf04e7c5686a9cb838c3f36a8cb6a0fc2bd (21/21)Ref 'refs/heads/master' was rewritten

The --tree-filter option runs the specified command after each checkout of the project and then recommits the results.

In this case, you remove a file called passwords.txt from every snapshot, whether it exists or not.

If you want to remove all accidentally committed editor backup files, you can run something like git filter-branch --tree-filter 'rm -f *~' HEAD.

You’ll be able to watch Git rewriting trees and commits and then move the branch pointer at the end.

It’s generally a good idea to do this in a testing branch and then hard-reset your master branch after you’ve determined the outcome is what you really want.

To run filter-branch on all your branches, you can pass --all to the command.

Making a Subdirectory the New Root

Suppose you’ve done an import from another source control system and have subdirectories that make no sense (trunk, tags, and so on).

If you want to make the trunk subdirectory be the new project root for every commit, filter-branch can help you do that, too:

$git filter-branch --subdirectory-filter trunk HEADRewrite 856f0bf61e41a27326cdae8f09fe708d679f596f (12/12)Ref 'refs/heads/master' was rewritten

Now your new project root is what was in the trunk subdirectory each time.

Git will also automatically remove commits that did not affect the subdirectory.

Changing Email Addresses Globally

Another common case is that you forgot to run git config to set your name and email address before you started working, or perhaps you want to open-source a project at work and change all your work email addresses to your personal address.

In any case, you can change email addresses in multiple commits in a batch with filter-branch as well.

You need to be careful to change only the email addresses that are yours, so you use --commit-filter:

$git filter-branch --commit-filter'if [ "$GIT_AUTHOR_EMAIL" = "schacon@localhost" ];thenGIT_AUTHOR_NAME="Scott Chacon";GIT_AUTHOR_EMAIL="schacon@example.com";git commit-tree "$@";elsegit commit-tree "$@";fi' HEAD

This goes through and rewrites every commit to have your new address. Because commits contain the SHA-1 values of their parents, this command changes every commit SHA-1 in your history, not just those that have the matching email address.

Reset Demystified

Before moving on to more specialized tools, let’s talk about reset and checkout.

These commands are two of the most confusing parts of Git when you first encounter them.

They do so many things, that it seems hopeless to actually understand them and employ them properly.

For this, we recommend a simple metaphor.

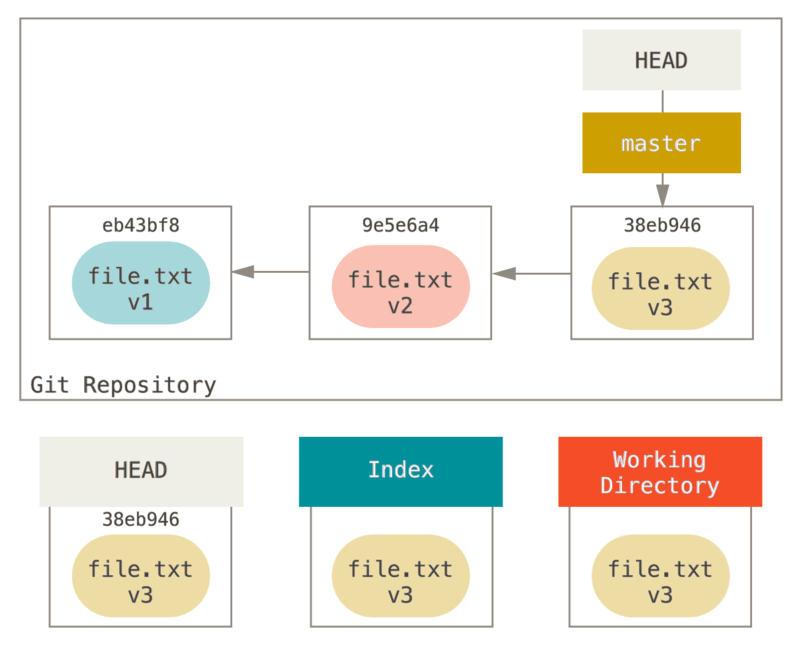

The Three Trees

An easier way to think about reset and checkout is through the mental frame of Git being a content manager of three different trees.

By “tree” here we really mean “collection of files”, not specifically the data structure.

(There are a few cases where the index doesn’t exactly act like a tree, but for our purposes it is easier to think about it this way for now.)

Git as a system manages and manipulates three trees in its normal operation:

| Tree | Role |

|---|---|

HEAD |

Last commit snapshot, next parent |

Index |

Proposed next commit snapshot |

Working Directory |

Sandbox |

The HEAD

HEAD is the pointer to the current branch reference, which is in turn a pointer to the last commit made on that branch. That means HEAD will be the parent of the next commit that is created. It’s generally simplest to think of HEAD as the snapshot of your last commit.

In fact, it’s pretty easy to see what that snapshot looks like. Here is an example of getting the actual directory listing and SHA-1 checksums for each file in the HEAD snapshot:

$git cat-file -p HEADtree cfda3bf379e4f8dba8717dee55aab78aef7f4dafauthor Scott Chacon 1301511835 -0700committer Scott Chacon 1301511835 -0700initial commit$git ls-tree -r HEAD100644 blob a906cb2a4a904a152... README100644 blob 8f94139338f9404f2... Rakefile040000 tree 99f1a6d12cb4b6f19... lib

The cat-file and ls-tree commands are “plumbing” commands that are used for lower level things and not really used in day-to-day work, but they help us see what’s going on here.

The Index

The Index is your proposed next commit.

We’ve also been referring to this concept as Git’s “Staging Area” as this is what Git looks at when you run git commit.

Git populates this index with a list of all the file contents that were last checked out into your working directory and what they looked like when they were originally checked out.

You then replace some of those files with new versions of them, and git commit converts that into the tree for a new commit.

$git ls-files -s100644 a906cb2a4a904a152e80877d4088654daad0c859 0 README100644 8f94139338f9404f26296befa88755fc2598c289 0 Rakefile100644 47c6340d6459e05787f644c2447d2595f5d3a54b 0 lib/simplegit.rb

Again, here we’re using ls-files, which is more of a behind the scenes command that shows you what your index currently looks like.

The index is not technically a tree structure – it’s actually implemented as a flattened manifest – but for our purposes it’s close enough.

The Working Directory

Finally, you have your working directory.

The other two trees store their content in an efficient but inconvenient manner, inside the .git folder.

The Working Directory unpacks them into actual files, which makes it much easier for you to edit them.

Think of the Working Directory as a sandbox, where you can try changes out before committing them to your staging area (index) and then to history.

$tree.├── README├── Rakefile└── lib└── simplegit.rb1 directory, 3 files

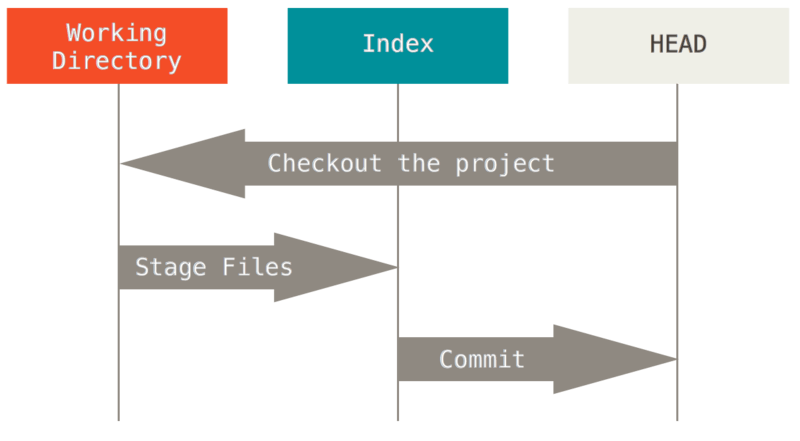

The Workflow

Git’s main purpose is to record snapshots of your project in successively better states, by manipulating these three trees.

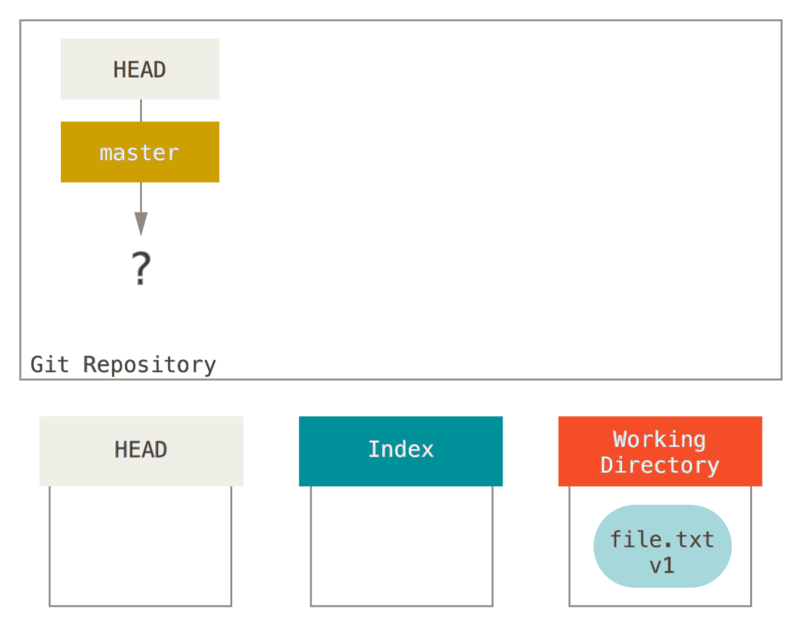

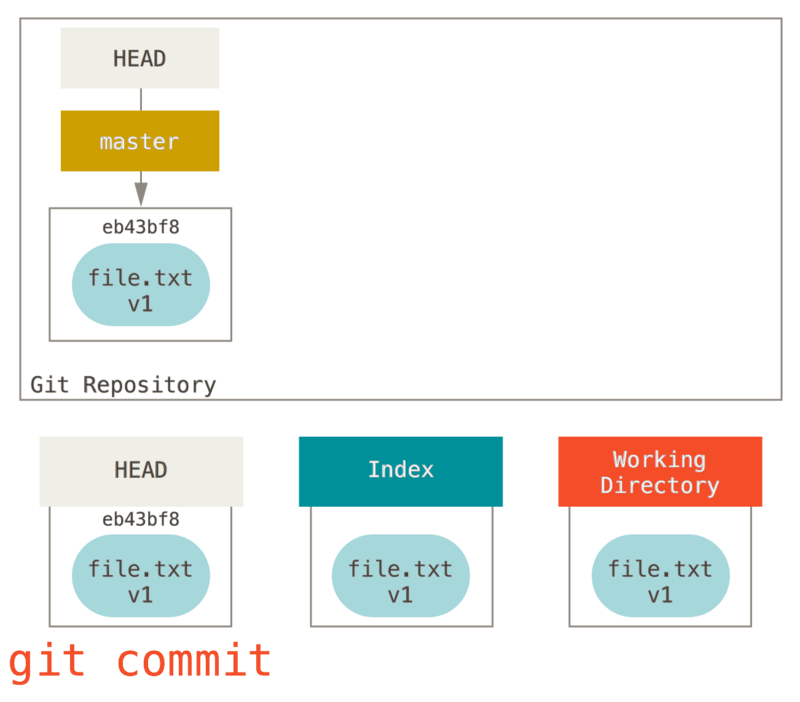

Let’s visualize this process: say you go into a new directory with a single file in it.

We’ll call this v1 of the file, and we’ll indicate it in blue.

Now we run git init, which will create a Git repository with a HEAD reference which points to an unborn branch (master doesn’t exist yet).

At this point, only the Working Directory tree has any content.

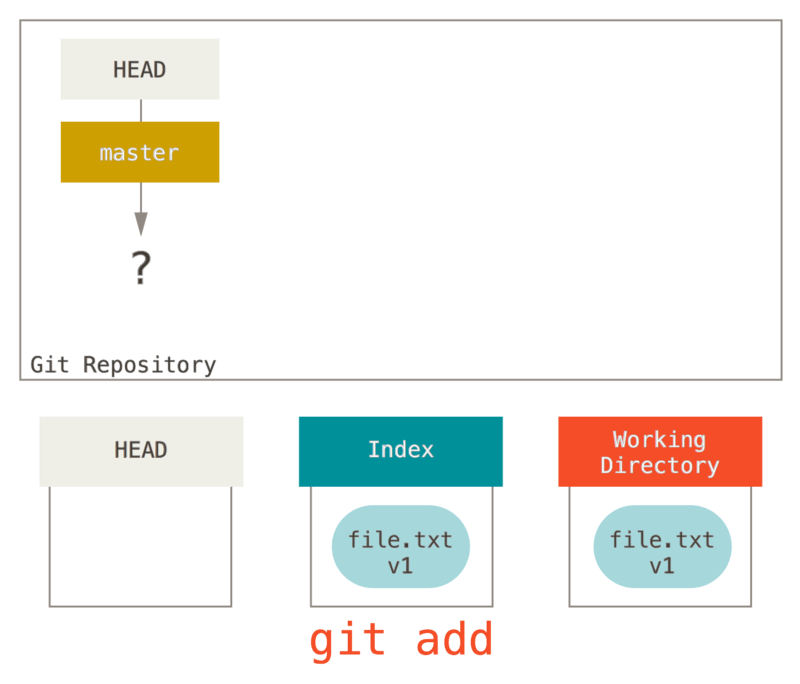

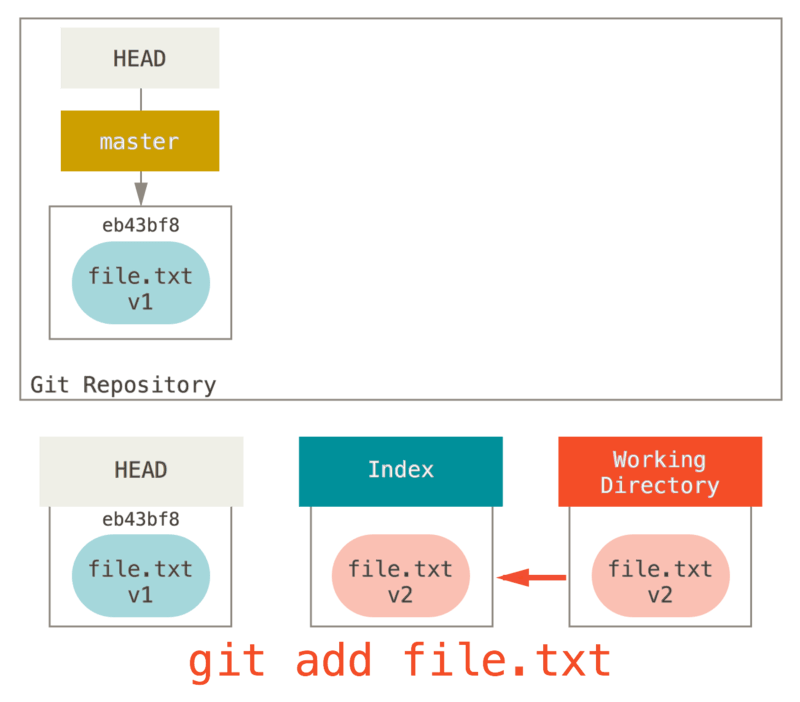

Now we want to commit this file, so we use git add to take content in the Working Directory and copy it to the Index.

Then we run git commit, which takes the contents of the Index and saves it as a permanent snapshot, creates a commit object which points to that snapshot, and updates master to point to that commit.

If we run git status, we’ll see no changes, because all three trees are the same.

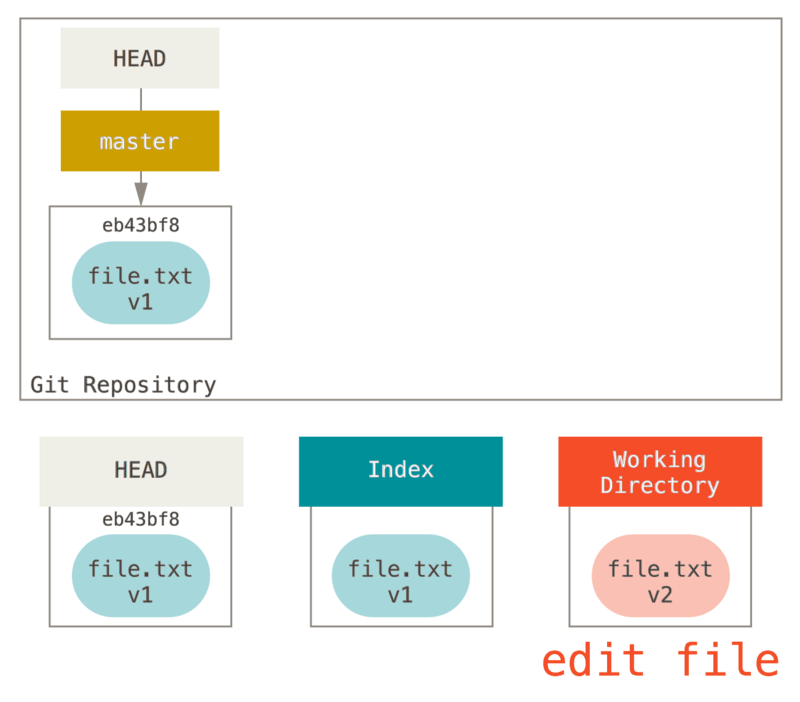

Now we want to make a change to that file and commit it. We’ll go through the same process; first we change the file in our working directory. Let’s call this v2 of the file, and indicate it in red.

If we run git status right now, we’ll see the file in red as “Changes not staged for commit,” because that entry differs between the Index and the Working Directory.

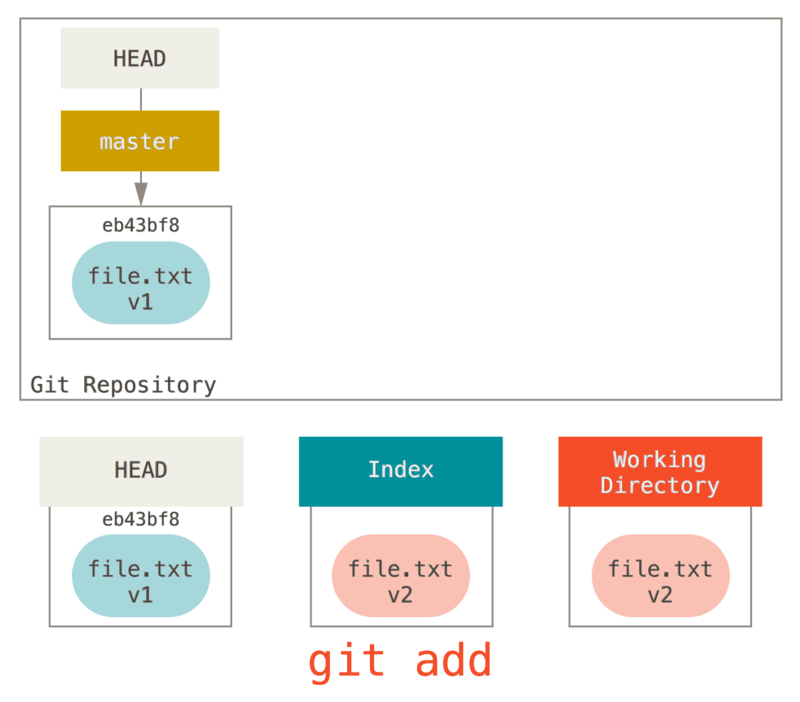

Next we run git add on it to stage it into our Index.

At this point if we run git status we will see the file in green

under “Changes to be committed” because the Index and HEAD differ – that is, our proposed next commit is now different from our last commit.

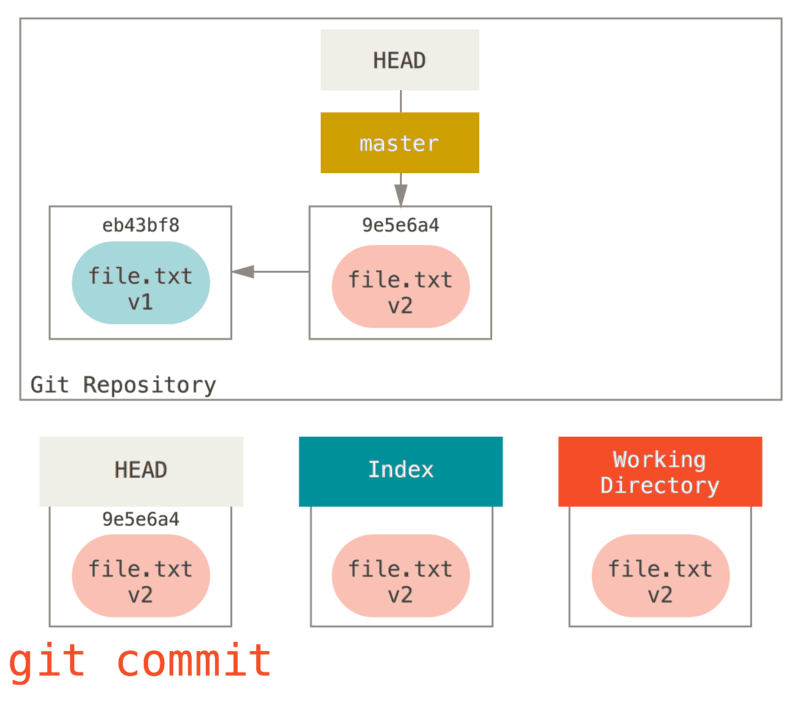

Finally, we run git commit to finalize the commit.

Now git status will give us no output, because all three trees are the same again.

Switching branches or cloning goes through a similar process. When you checkout a branch, it changes HEAD to point to the new branch ref, populates your Index with the snapshot of that commit, then copies the contents of the Index into your Working Directory.

The Role of Reset

The reset command makes more sense when viewed in this context.

For the purposes of these examples, let’s say that we’ve modified file.txt again and committed it a third time.

So now our history looks like this:

Let’s now walk through exactly what reset does when you call it.

It directly manipulates these three trees in a simple and predictable way.

It does up to three basic operations.

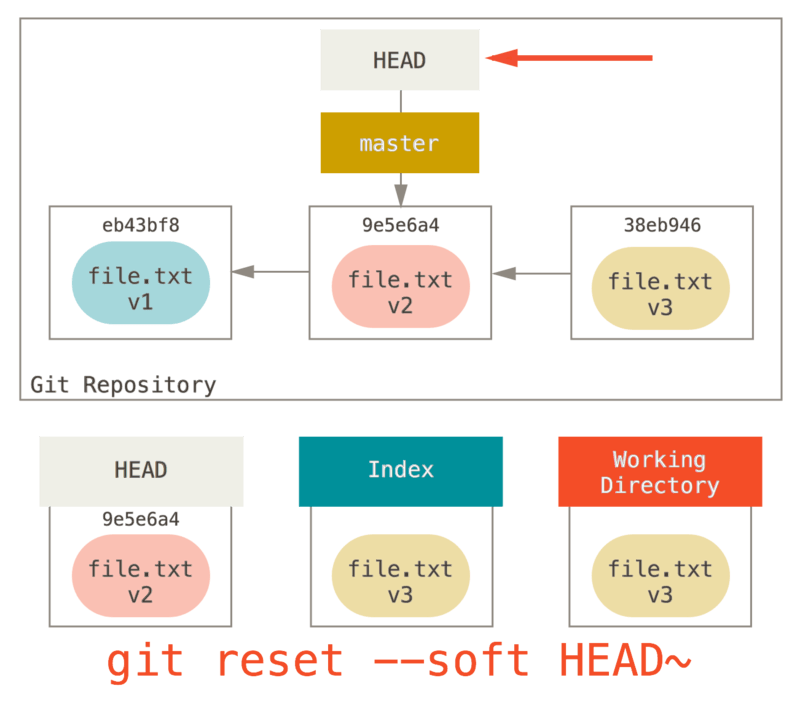

Step 1: Move HEAD

The first thing reset will do is move what HEAD points to.

This isn’t the same as changing HEAD itself (which is what checkout does); reset moves the branch that HEAD is pointing to.

This means if HEAD is set to the master branch (i.e. you’re currently on the master branch), running git reset 9e5e6a4 will start by making master point to 9e5e6a4.

No matter what form of reset with a commit you invoke, this is the first thing it will always try to do.

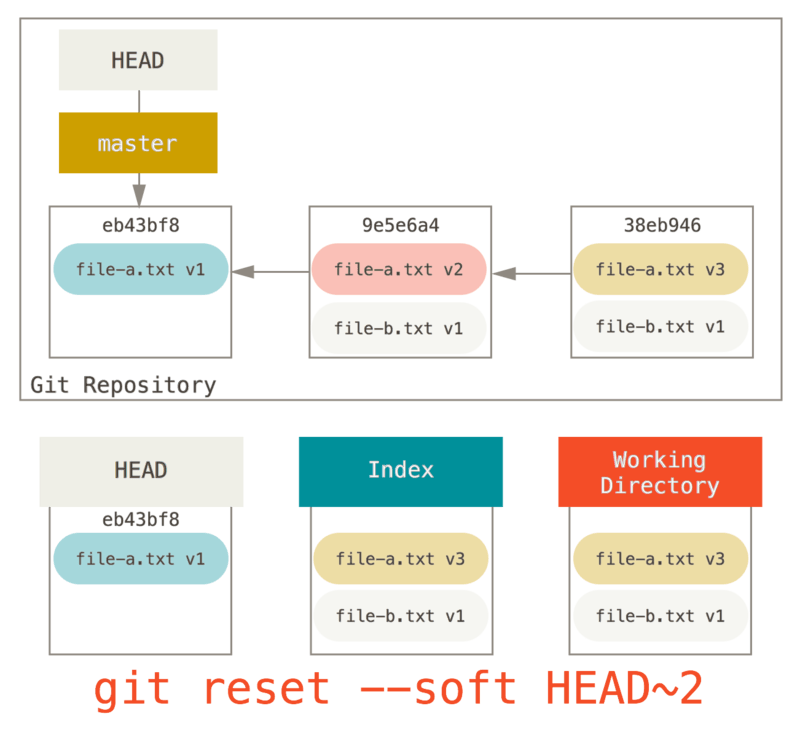

With reset --soft, it will simply stop there.

Now take a second to look at that diagram and realize what happened: it essentially undid the last git commit command.

When you run git commit, Git creates a new commit and moves the branch that HEAD points to up to it.

When you reset back to HEAD~ (the parent of HEAD), you are moving the branch back to where it was, without changing the Index or Working Directory.

You could now update the Index and run git commit again to accomplish what git commit --amend would have done (see Changing the Last Commit).

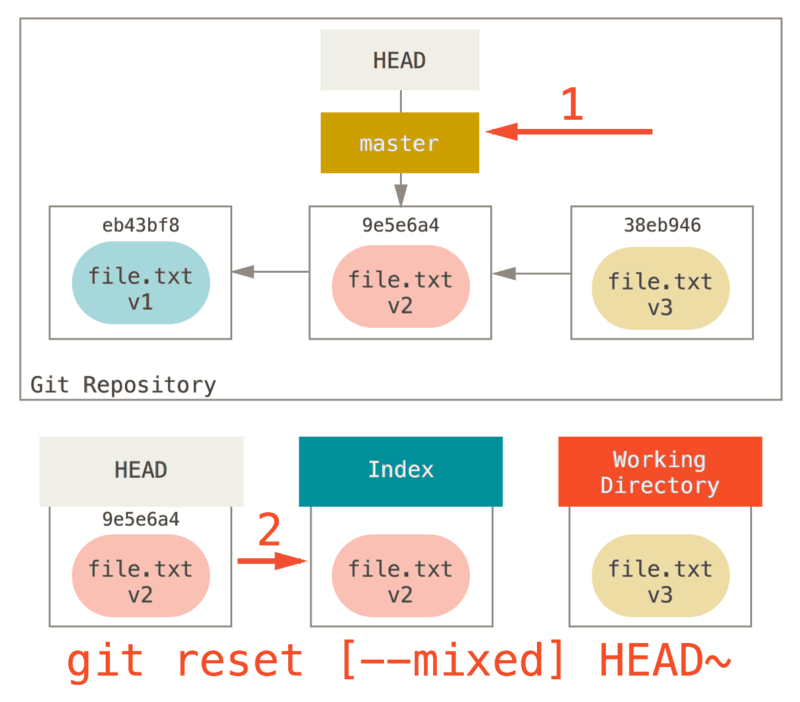

Step 2: Updating the Index (--mixed)

Note that if you run git status now you’ll see in green the difference between the Index and what the new HEAD is.

The next thing reset will do is to update the Index with the contents of whatever snapshot HEAD now points to.

If you specify the --mixed option, reset will stop at this point.

This is also the default, so if you specify no option at all (just git reset HEAD~ in this case), this is where the command will stop.

Now take another second to look at that diagram and realize what happened: it still undid your last commit, but also unstaged everything.

You rolled back to before you ran all your git add and git commit commands.

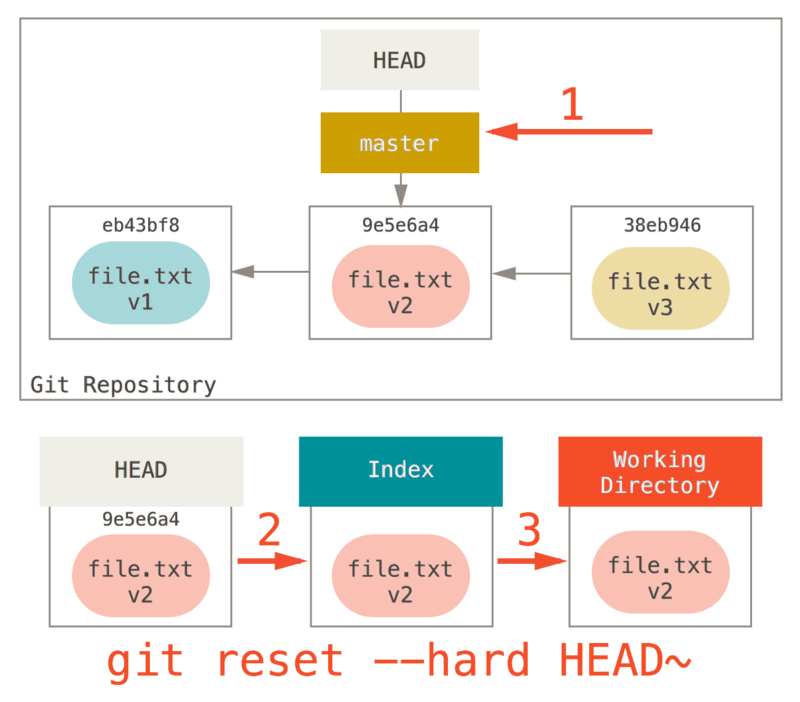

Step 3: Updating the Working Directory (--hard)

The third thing that reset will do is to make the Working Directory look like the Index.

If you use the --hard option, it will continue to this stage.

So let’s think about what just happened.

You undid your last commit, the git add and git commit commands, and all the work you did in your working directory.

It’s important to note that this flag (--hard) is the only way to make the reset command dangerous, and one of the very few cases where Git will actually destroy data.

Any other invocation of reset can be pretty easily undone, but the --hard option cannot, since it forcibly overwrites files in the Working Directory.

In this particular case, we still have the v3 version of our file in a commit in our Git DB, and we could get it back by looking at our reflog, but if we had not committed it, Git still would have overwritten the file and it would be unrecoverable.

Recap

The reset command overwrites these three trees in a specific order, stopping when you tell it to:

-

Move the branch HEAD points to (stop here if

--soft) -

Make the Index look like HEAD (stop here unless

--hard) -

Make the Working Directory look like the Index

Reset With a Path

That covers the behavior of reset in its basic form, but you can also provide it with a path to act upon.

If you specify a path, reset will skip step 1, and limit the remainder of its actions to a specific file or set of files.

This actually sort of makes sense – HEAD is just a pointer, and you can’t point to part of one commit and part of another.

But the Index and Working directory can be partially updated, so reset proceeds with steps 2 and 3.

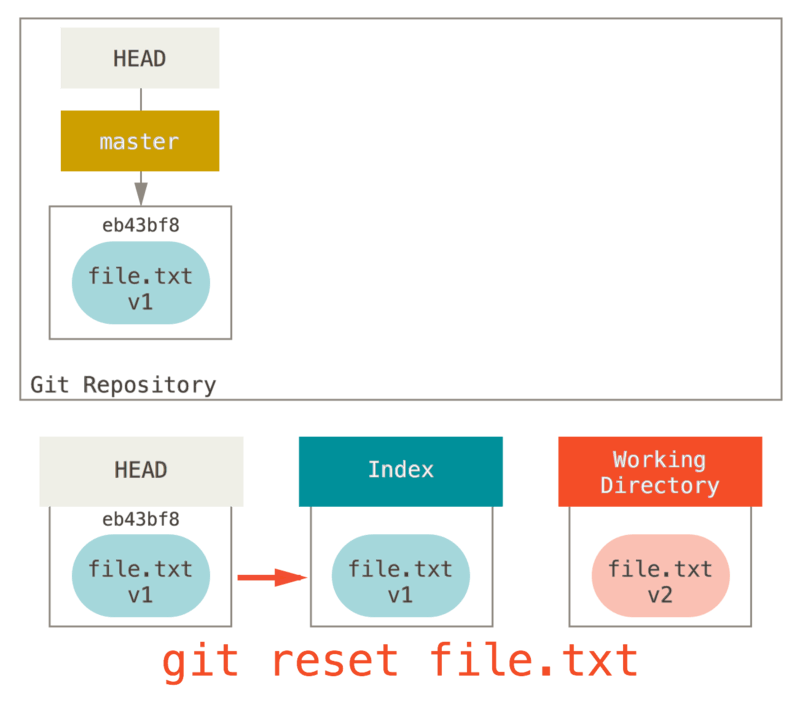

So, assume we run git reset file.txt.

This form (since you did not specify a commit SHA-1 or branch, and you didn’t specify --soft or --hard) is shorthand for git reset --mixed HEAD file.txt, which will:

-

Move the branch HEAD points to (skipped)

-

Make the Index look like HEAD (stop here)

So it essentially just copies file.txt from HEAD to the Index.

This has the practical effect of unstaging the file.

If we look at the diagram for that command and think about what git add does, they are exact opposites.

This is why the output of the git status command suggests that you run this to unstage a file.

(See Unstaging a Staged File for more on this.)

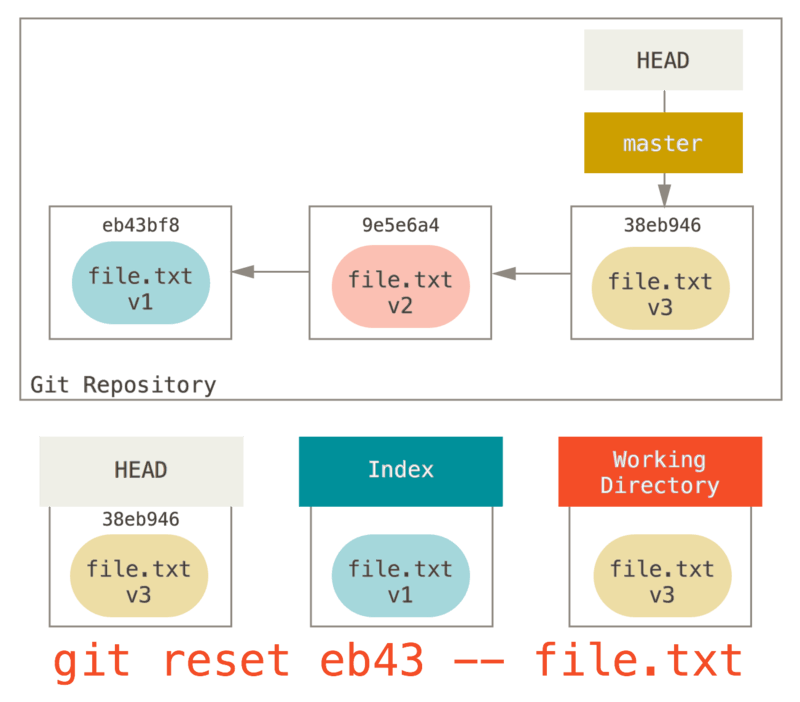

We could just as easily not let Git assume we meant “pull the data from HEAD” by specifying a specific commit to pull that file version from.

We would just run something like git reset eb43bf file.txt.

This effectively does the same thing as if we had reverted the content of the file to v1 in the Working Directory, ran git add on it, then reverted it back to v3 again (without actually going through all those steps).

If we run git commit now, it will record a change that reverts that file back to v1, even though we never actually had it in our Working Directory again.

It’s also interesting to note that like git add, the reset command will accept a --patch option to unstage content on a hunk-by-hunk basis.

So you can selectively unstage or revert content.

Squashing

Let’s look at how to do something interesting with this newfound power – squashing commits.

Say you have a series of commits with messages like “oops.”, “WIP” and “forgot this file”.

You can use reset to quickly and easily squash them into a single commit that makes you look really smart.

(Squashing Commits shows another way to do this, but in this example it’s simpler to use reset.)

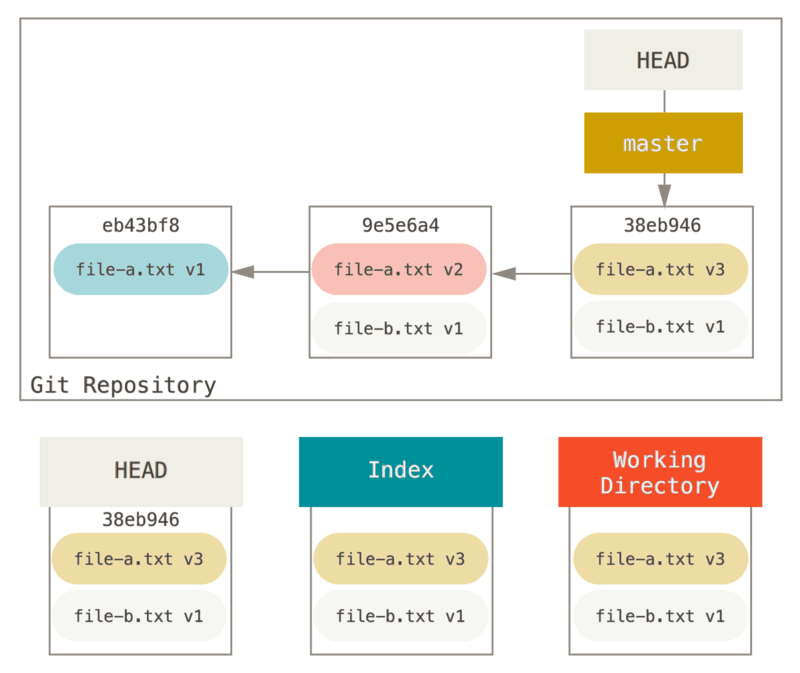

Let’s say you have a project where the first commit has one file, the second commit added a new file and changed the first, and the third commit changed the first file again. The second commit was a work in progress and you want to squash it down.

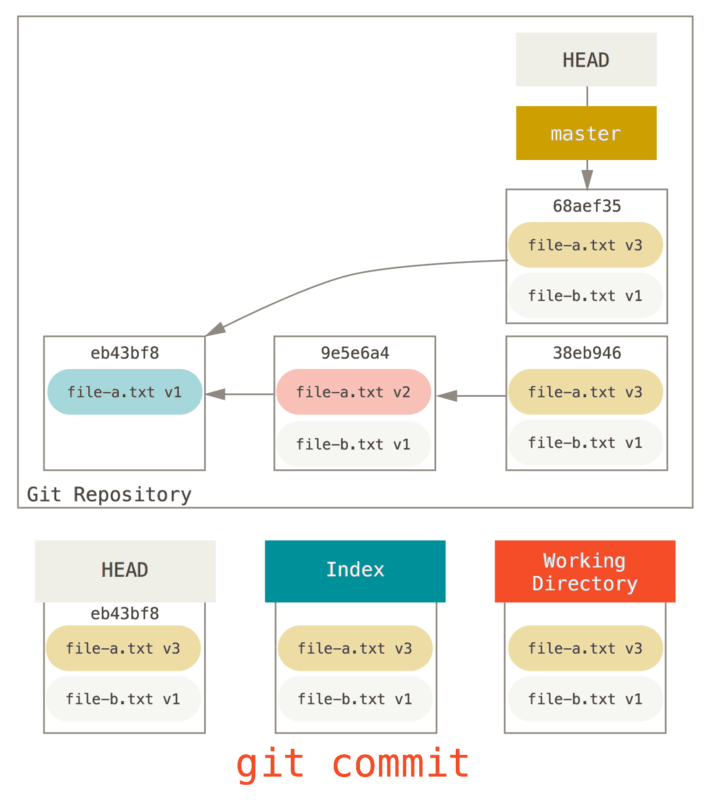

You can run git reset --soft HEAD~2 to move the HEAD branch back to an older commit (the first commit you want to keep):

And then simply run git commit again:

Now you can see that your reachable history, the history you would push, now looks like you had one commit with file-a.txt v1, then a second that both modified file-a.txt to v3 and added file-b.txt.

The commit with the v2 version of the file is no longer in the history.

Check It Out

Finally, you may wonder what the difference between checkout and reset is.

Like reset, checkout manipulates the three trees, and it is a bit different depending on whether you give the command a file path or not.

Without Paths

Running git checkout [branch] is pretty similar to running git reset --hard [branch] in that it updates all three trees for you to look like [branch], but there are two important differences.

First, unlike reset --hard, checkout is working-directory safe; it will check to make sure it’s not blowing away files that have changes to them.

Actually, it’s a bit smarter than that – it tries to do a trivial merge in the Working Directory, so all of the files you haven’t changed in will be updated.

reset --hard, on the other hand, will simply replace everything across the board without checking.

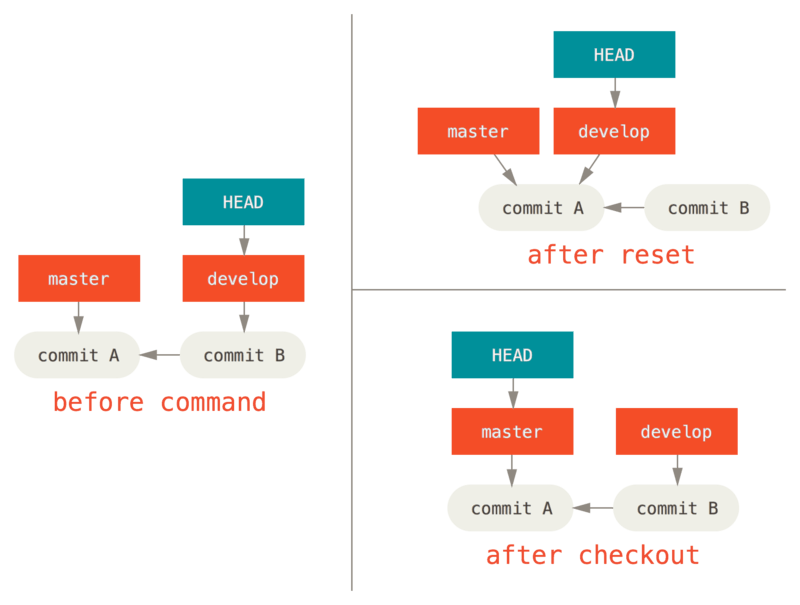

The second important difference is how it updates HEAD.

Where reset will move the branch that HEAD points to, checkout will move HEAD itself to point to another branch.

For instance, say we have master and develop branches which point at different commits, and we’re currently on develop (so HEAD points to it).

If we run git reset master, develop itself will now point to the same commit that master does.

If we instead run git checkout master, develop does not move, HEAD itself does.

HEAD will now point to master.

So, in both cases we’re moving HEAD to point to commit A, but how we do so is very different.

reset will move the branch HEAD points to, checkout moves HEAD itself.

With Paths

The other way to run checkout is with a file path, which, like reset, does not move HEAD.

It is just like git reset [branch] file in that it updates the index with that file at that commit, but it also overwrites the file in the working directory.

It would be exactly like git reset --hard [branch] file (if reset would let you run that) – it’s not working-directory safe, and it does not move HEAD.

Also, like git reset and git add, checkout will accept a --patch option to allow you to selectively revert file contents on a hunk-by-hunk basis.

Summary

Hopefully now you understand and feel more comfortable with the reset command, but are probably still a little confused about how exactly it differs from checkout and could not possibly remember all the rules of the different invocations.

Here’s a cheat-sheet for which commands affect which trees. The “HEAD” column reads “REF” if that command moves the reference (branch) that HEAD points to, and “HEAD” if it moves HEAD itself. Pay especial attention to the WD Safe? column – if it says NO, take a second to think before running that command.

| HEAD | Index | Workdir | WD Safe? | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Commit Level |

||||

|

REF |

NO |

NO |

YES |

|

REF |

YES |

NO |

YES |

|

REF |

YES |

YES |

NO |

|

HEAD |

YES |

YES |

YES |

File Level |

||||

|

NO |

YES |

NO |

YES |

|

NO |

YES |

YES |

NO |

Advanced Merging

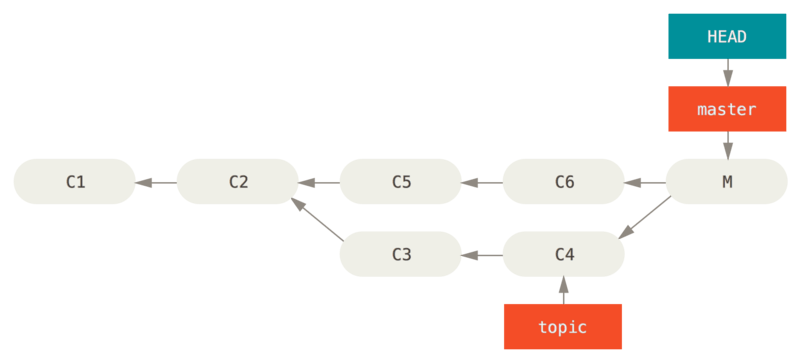

Merging in Git is typically fairly easy. Since Git makes it easy to merge another branch multiple times, it means that you can have a very long lived branch but you can keep it up to date as you go, solving small conflicts often, rather than be surprised by one enormous conflict at the end of the series.

However, sometimes tricky conflicts do occur. Unlike some other version control systems, Git does not try to be overly clever about merge conflict resolution. Git’s philosophy is to be smart about determining when a merge resolution is unambiguous, but if there is a conflict, it does not try to be clever about automatically resolving it. Therefore, if you wait too long to merge two branches that diverge quickly, you can run into some issues.

In this section, we’ll go over what some of those issues might be and what tools Git gives you to help handle these more tricky situations. We’ll also cover some of the different, non-standard types of merges you can do, as well as see how to back out of merges that you’ve done.

Merge Conflicts

While we covered some basics on resolving merge conflicts in Basic Merge Conflicts, for more complex conflicts, Git provides a few tools to help you figure out what’s going on and how to better deal with the conflict.

First of all, if at all possible, try to make sure your working directory is clean before doing a merge that may have conflicts. If you have work in progress, either commit it to a temporary branch or stash it. This makes it so that you can undo anything you try here. If you have unsaved changes in your working directory when you try a merge, some of these tips may help you lose that work.

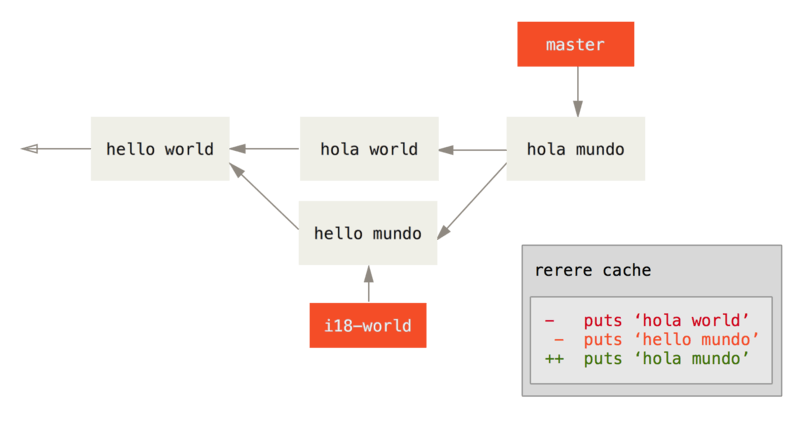

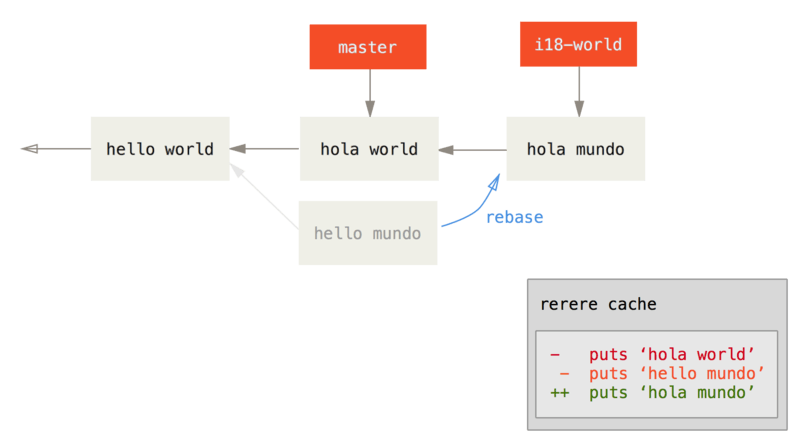

Let’s walk through a very simple example. We have a super simple Ruby file that prints hello world.

#! /usr/bin/env rubydefhelloputs'hello world'endhello()

In our repository, we create a new branch named whitespace and proceed to change all the Unix line endings to DOS line endings, essentially changing every line of the file, but just with whitespace.

Then we change the line “hello world” to “hello mundo”.

$git checkout -b whitespaceSwitched to a new branch 'whitespace'$unix2dos hello.rbunix2dos: converting file hello.rb to DOS format ...$git commit -am'converted hello.rb to DOS'[whitespace 3270f76] converted hello.rb to DOS1 file changed, 7 insertions(+), 7 deletions(-)$vim hello.rb$git diff -bdiff --git a/hello.rb b/hello.rbindex ac51efd..e85207e 100755--- a/hello.rb+++ b/hello.rb@@ -1,7 +1,7 @@#! /usr/bin/env rubydef hello- puts 'hello world'+ puts 'hello mundo'^Mendhello()$git commit -am'hello mundo change'[whitespace 6d338d2] hello mundo change1 file changed, 1 insertion(+), 1 deletion(-)

Now we switch back to our master branch and add some documentation for the function.

$git checkout masterSwitched to branch 'master'$vim hello.rb$git diffdiff --git a/hello.rb b/hello.rbindex ac51efd..36c06c8 100755--- a/hello.rb+++ b/hello.rb@@ -1,5 +1,6 @@#! /usr/bin/env ruby+# prints out a greetingdef helloputs 'hello world'end$git commit -am'document the function'[master bec6336] document the function1 file changed, 1 insertion(+)

Now we try to merge in our whitespace branch and we’ll get conflicts because of the whitespace changes.

$git merge whitespaceAuto-merging hello.rbCONFLICT (content): Merge conflict in hello.rbAutomatic merge failed; fix conflicts and then commit the result.

Aborting a Merge

We now have a few options.

First, let’s cover how to get out of this situation.

If you perhaps weren’t expecting conflicts and don’t want to quite deal with the situation yet, you can simply back out of the merge with git merge --abort.

$git status -sb## masterUU hello.rb$git merge --abort$git status -sb## master

The git merge --abort option tries to revert back to your state before you ran the merge.

The only cases where it may not be able to do this perfectly would be if you had unstashed, uncommitted changes in your working directory when you ran it, otherwise it should work fine.

If for some reason you just want to start over, you can also run git reset --hard HEAD, and your repository will be back to the last committed state.

Remember that any uncommitted work will be lost, so make sure you don’t want any of your changes.

Ignoring Whitespace

In this specific case, the conflicts are whitespace related. We know this because the case is simple, but it’s also pretty easy to tell in real cases when looking at the conflict because every line is removed on one side and added again on the other. By default, Git sees all of these lines as being changed, so it can’t merge the files.

The default merge strategy can take arguments though, and a few of them are about properly ignoring whitespace changes.

If you see that you have a lot of whitespace issues in a merge, you can simply abort it and do it again, this time with -Xignore-all-space or -Xignore-space-change.

The first option ignores whitespace completely when comparing lines, the second treats sequences of one or more whitespace characters as equivalent.

$git merge -Xignore-space-change whitespaceAuto-merging hello.rbMerge made by the 'recursive' strategy.hello.rb | 2 +-1 file changed, 1 insertion(+), 1 deletion(-)

Since in this case, the actual file changes were not conflicting, once we ignore the whitespace changes, everything merges just fine.

This is a lifesaver if you have someone on your team who likes to occasionally reformat everything from spaces to tabs or vice-versa.

Manual File Re-merging

Though Git handles whitespace pre-processing pretty well, there are other types of changes that perhaps Git can’t handle automatically, but are scriptable fixes. As an example, let’s pretend that Git could not handle the whitespace change and we needed to do it by hand.

What we really need to do is run the file we’re trying to merge in through a dos2unix program before trying the actual file merge.

So how would we do that?

First, we get into the merge conflict state. Then we want to get copies of my version of the file, their version (from the branch we’re merging in) and the common version (from where both sides branched off). Then we want to fix up either their side or our side and re-try the merge again for just this single file.

Getting the three file versions is actually pretty easy.

Git stores all of these versions in the index under “stages” which each have numbers associated with them.

Stage 1 is the common ancestor, stage 2 is your version and stage 3 is from the MERGE_HEAD, the version you’re merging in (“theirs”).

You can extract a copy of each of these versions of the conflicted file with the git show command and a special syntax.

$git show :1:hello.rb>hello.common.rb$git show :2:hello.rb>hello.ours.rb$git show :3:hello.rb>hello.theirs.rb

If you want to get a little more hard core, you can also use the ls-files -u plumbing command to get the actual SHA-1s of the Git blobs for each of these files.

$git ls-files -u100755 ac51efdc3df4f4fd328d1a02ad05331d8e2c9111 1 hello.rb100755 36c06c8752c78d2aff89571132f3bf7841a7b5c3 2 hello.rb100755 e85207e04dfdd5eb0a1e9febbc67fd837c44a1cd 3 hello.rb

The :1:hello.rb is just a shorthand for looking up that blob SHA-1.

Now that we have the content of all three stages in our working directory, we can manually fix up theirs to fix the whitespace issue and re-merge the file with the little-known git merge-file command which does just that.

$dos2unix hello.theirs.rbdos2unix: converting file hello.theirs.rb to Unix format ...$git merge-file -p\hello.ours.rb hello.common.rb hello.theirs.rb > hello.rb$git diff -bdiff --cc hello.rbindex 36c06c8,e85207e..0000000--- a/hello.rb+++ b/hello.rb@@@ -1,8 -1,7 +1,8 @@@#! /usr/bin/env ruby+# prints out a greetingdef hello- puts 'hello world'+ puts 'hello mundo'endhello()

At this point we have nicely merged the file.