GitHub

GitHub is the single largest host for Git repositories, and is the central point of collaboration for millions of developers and projects. A large percentage of all Git repositories are hosted on GitHub, and many open-source projects use it for Git hosting, issue tracking, code review, and other things. So while it’s not a direct part of the Git open source project, there’s a good chance that you’ll want or need to interact with GitHub at some point while using Git professionally.

This chapter is about using GitHub effectively. We’ll cover signing up for and managing an account, creating and using Git repositories, common workflows to contribute to projects and to accept contributions to yours, GitHub’s programmatic interface and lots of little tips to make your life easier in general.

If you are not interested in using GitHub to host your own projects or to collaborate with other projects that are hosted on GitHub, you can safely skip to Git Tools.

Warning

Interfaces Change

It’s important to note that like many active websites, the UI elements in these screenshots are bound to change over time. Hopefully the general idea of what we’re trying to accomplish here will still be there, but if you want more up to date versions of these screens, the online versions of this book may have newer screenshots.

Account Setup and Configuration

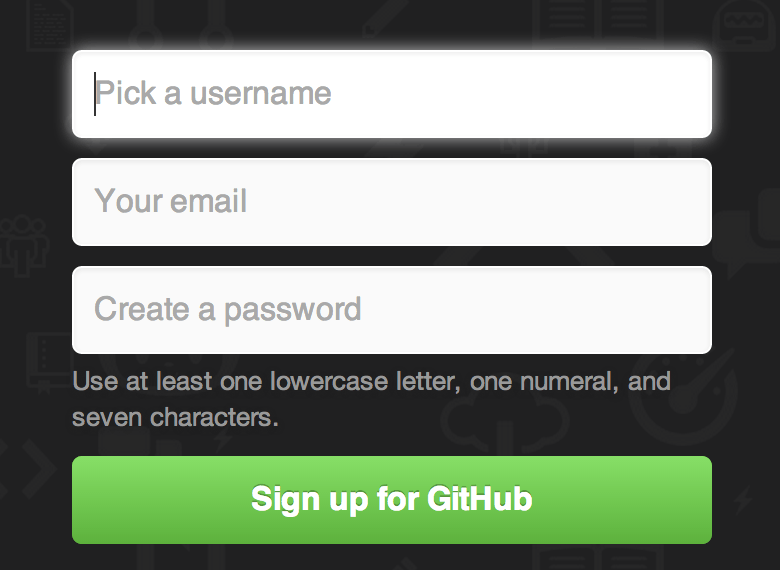

The first thing you need to do is set up a free user account. Simply visit https://github.com, choose a user name that isn’t already taken, provide an email address and a password, and click the big green “Sign up for GitHub” button.

The next thing you’ll see is the pricing page for upgraded plans, but it’s safe to ignore this for now. GitHub will send you an email to verify the address you provided. Go ahead and do this, it’s pretty important (as we’ll see later).

Note

GitHub provides all of its functionality with free accounts, with the limitation that all of your projects are fully public (everyone has read access). GitHub’s paid plans include a set number of private projects, but we won’t be covering those in this book.

Clicking the Octocat logo at the top-left of the screen will take you to your dashboard page. You’re now ready to use GitHub.

SSH Access

As of right now, you’re fully able to connect with Git repositories using the https:// protocol, authenticating with the username and password you just set up.

However, to simply clone public projects, you don’t even need to sign up - the account we just created comes into play when we fork projects and push to our forks a bit later.

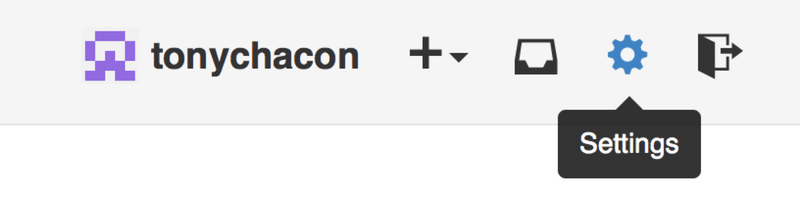

If you’d like to use SSH remotes, you’ll need to configure a public key. (If you don’t already have one, see Generating Your SSH Public Key.) Open up your account settings using the link at the top-right of the window:

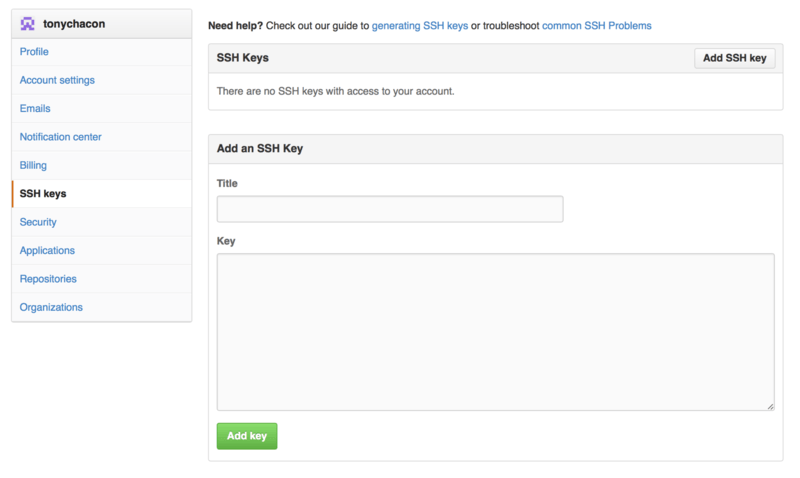

Then select the “SSH keys” section along the left-hand side.

From there, click the "Add an SSH key" button, give your key a name, paste the contents of your ~/.ssh/id_rsa.pub (or whatever you named it) public-key file into the text area, and click “Add key”.

Note

Be sure to name your SSH key something you can remember. You can name each of your keys (e.g. "My Laptop" or "Work Account") so that if you need to revoke a key later, you can easily tell which one you’re looking for.

Your Avatar

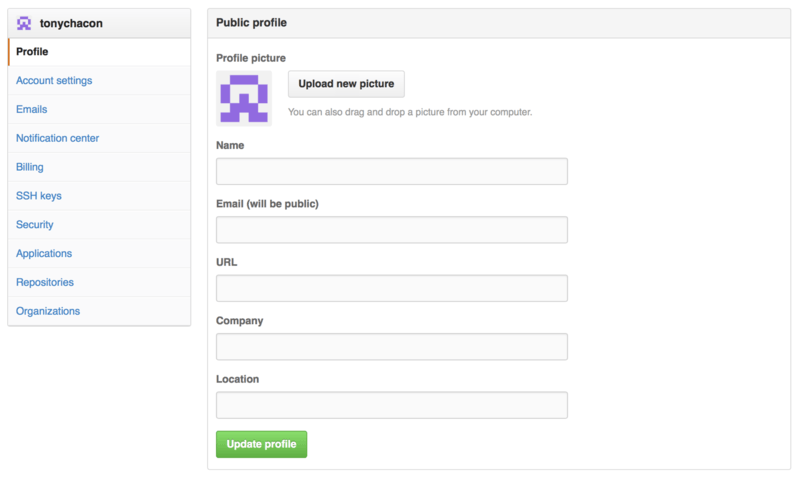

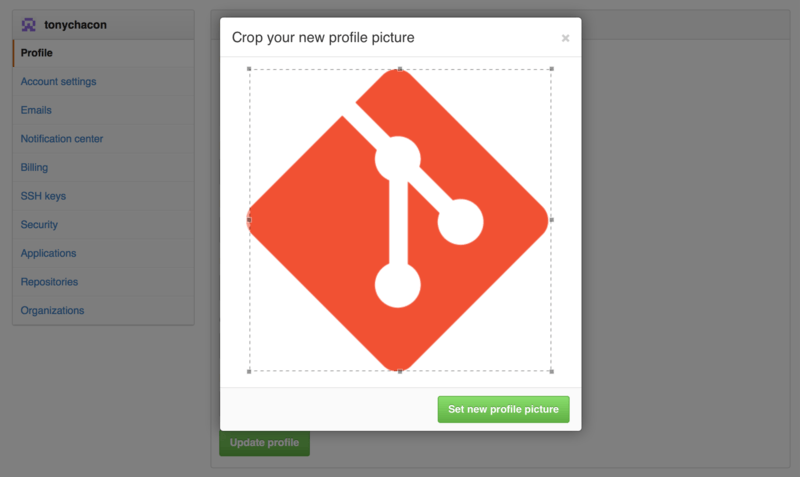

Next, if you wish, you can replace the avatar that is generated for you with an image of your choosing. First go to the “Profile” tab (above the SSH Keys tab) and click “Upload new picture”.

We’ll choose a copy of the Git logo that is on our hard drive and then we get a chance to crop it.

Now anywhere you interact on the site, people will see your avatar next to your username.

If you happen to have uploaded an avatar to the popular Gravatar service (often used for Wordpress accounts), that avatar will be used by default and you don’t need to do this step.

Your Email Addresses

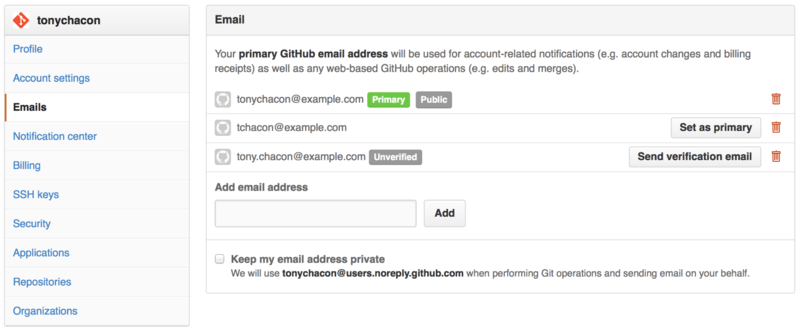

The way that GitHub maps your Git commits to your user is by email address. If you use multiple email addresses in your commits and you want GitHub to link them up properly, you need to add all the email addresses you have used to the Emails section of the admin section.

In Figure 6-6 we can see some of the different states that are possible. The top address is verified and set as the primary address, meaning that is where you’ll get any notifications and receipts. The second address is verified and so can be set as the primary if you wish to switch them. The final address is unverified, meaning that you can’t make it your primary address. If GitHub sees any of these in commit messages in any repository on the site, it will be linked to your user now.

Two Factor Authentication

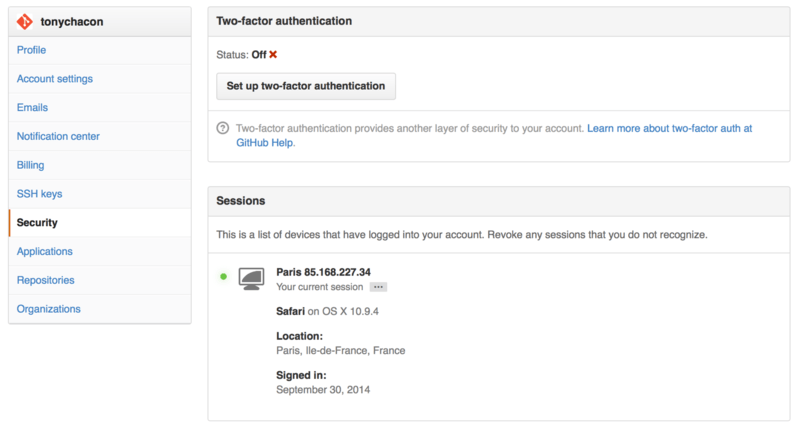

Finally, for extra security, you should definitely set up Two-factor Authentication or “2FA”. Two-factor Authentication is an authentication mechanism that is becoming more and more popular recently to mitigate the risk of your account being compromised if your password is stolen somehow. Turning it on will make GitHub ask you for two different methods of authentication, so that if one of them is compromised, an attacker will not be able to access your account.

You can find the Two-factor Authentication setup under the Security tab of your Account settings.

If you click on the “Set up two-factor authentication” button, it will take you to a configuration page where you can choose to use a phone app to generate your secondary code (a “time based one-time password”), or you can have GitHub send you a code via SMS each time you need to log in.

After you choose which method you prefer and follow the instructions for setting up 2FA, your account will then be a little more secure and you will have to provide a code in addition to your password whenever you log into GitHub.

Contributing to a Project

Now that our account is set up, let’s walk through some details that could be useful in helping you contribute to an existing project.

Forking Projects

If you want to contribute to an existing project to which you don’t have push access, you can “fork” the project. What this means is that GitHub will make a copy of the project that is entirely yours; it lives in your user’s namespace, and you can push to it.

Note

Historically, the term “fork” has been somewhat negative in context, meaning that someone took an open source project in a different direction, sometimes creating a competing project and splitting the contributors. In GitHub, a “fork” is simply the same project in your own namespace, allowing you to make changes to a project publicly as a way to contribute in a more open manner.

This way, projects don’t have to worry about adding users as collaborators to give them push access. People can fork a project, push to it, and contribute their changes back to the original repository by creating what’s called a Pull Request, which we’ll cover next. This opens up a discussion thread with code review, and the owner and the contributor can then communicate about the change until the owner is happy with it, at which point the owner can merge it in.

To fork a project, visit the project page and click the “Fork” button at the top-right of the page.

After a few seconds, you’ll be taken to your new project page, with your own writeable copy of the code.

The GitHub Flow

GitHub is designed around a particular collaboration workflow, centered on Pull Requests. This flow works whether you’re collaborating with a tightly-knit team in a single shared repository, or a globally-distributed company or network of strangers contributing to a project through dozens of forks. It is centered on the Topic Branches workflow covered in Git Branching.

Here’s how it generally works:

-

Create a topic branch from

master. -

Make some commits to improve the project.

-

Push this branch to your GitHub project.

-

Open a Pull Request on GitHub.

-

Discuss, and optionally continue committing.

-

The project owner merges or closes the Pull Request.

This is basically the Integration Manager workflow covered in Integration-Manager Workflow, but instead of using email to communicate and review changes, teams use GitHub’s web based tools.

Let’s walk through an example of proposing a change to an open source project hosted on GitHub using this flow.

Creating a Pull Request

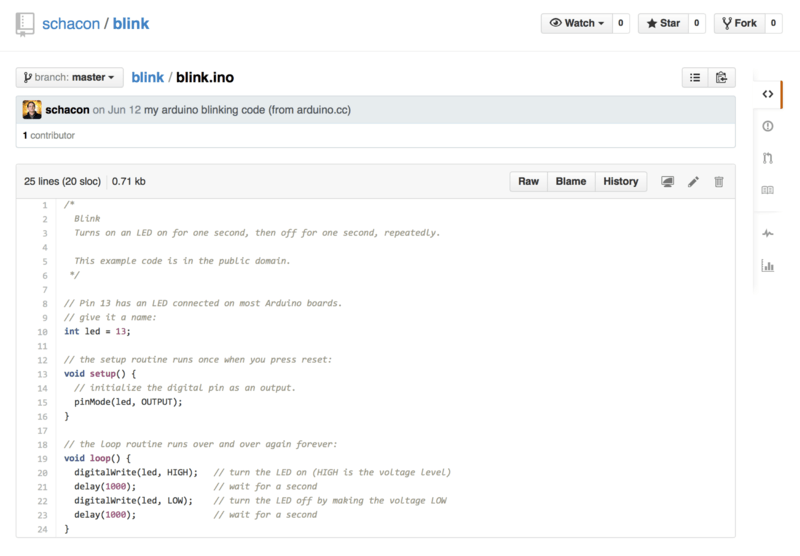

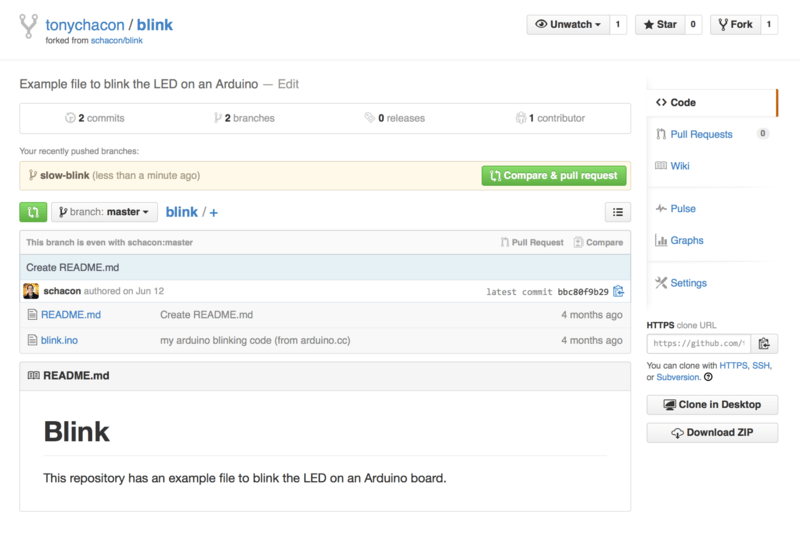

Tony is looking for code to run on his Arduino programmable microcontroller and has found a great program file on GitHub at https://github.com/schacon/blink.

The only problem is that the blinking rate is too fast, we think it’s much nicer to wait 3 seconds instead of 1 in between each state change. So let’s improve the program and submit it back to the project as a proposed change.

First, we click the Fork button as mentioned earlier to get our own copy of the project.

Our user name here is “tonychacon” so our copy of this project is at https://github.com/tonychacon/blink and that’s where we can edit it.

We will clone it locally, create a topic branch, make the code change and finally push that change back up to GitHub.

$ git clone https://github.com/tonychacon/blinkCloning into 'blink'... $ cd blink $ git checkout -b slow-blink

Switched to a new branch 'slow-blink' $ sed -i '' 's/1000/3000/' blink.ino

$ git diff --word-diff

diff --git a/blink.ino b/blink.ino index 15b9911..a6cc5a5 100644 --- a/blink.ino +++ b/blink.ino @@ -18,7 +18,7 @@ void setup() { // the loop routine runs over and over again forever: void loop() { digitalWrite(led, HIGH); // turn the LED on (HIGH is the voltage level) [-delay(1000);-]{+delay(3000);+} // wait for a second digitalWrite(led, LOW); // turn the LED off by making the voltage LOW [-delay(1000);-]{+delay(3000);+} // wait for a second } $ git commit -a -m 'three seconds is better'

[slow-blink 5ca509d] three seconds is better 1 file changed, 2 insertions(+), 2 deletions(-) $ git push origin slow-blink

Username for 'https://github.com': tonychacon Password for 'https://tonychacon@github.com': Counting objects: 5, done. Delta compression using up to 8 threads. Compressing objects: 100% (3/3), done. Writing objects: 100% (3/3), 340 bytes | 0 bytes/s, done. Total 3 (delta 1), reused 0 (delta 0) To https://github.com/tonychacon/blink * [new branch] slow-blink -> slow-blink

Clone our fork of the project locally

Create a descriptive topic branch

Make our change to the code

Check that the change is good

Commit our change to the topic branch

Push our new topic branch back up to our GitHub fork

Now if we go back to our fork on GitHub, we can see that GitHub noticed that we pushed a new topic branch up and present us with a big green button to check out our changes and open a Pull Request to the original project.

You can alternatively go to the “Branches” page at https://github.com/<user>/<project>/branches to locate your branch and open a new Pull Request from there.

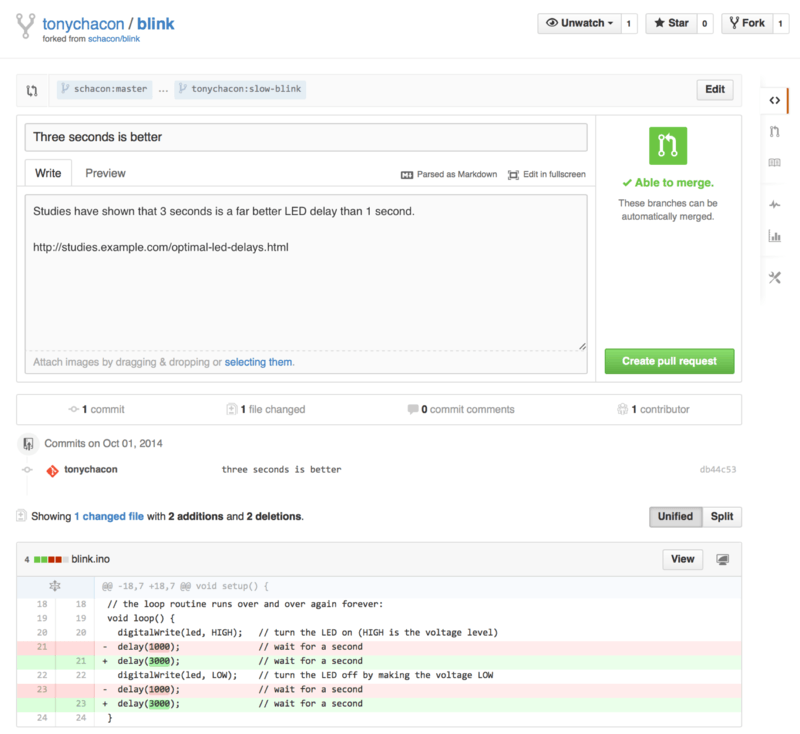

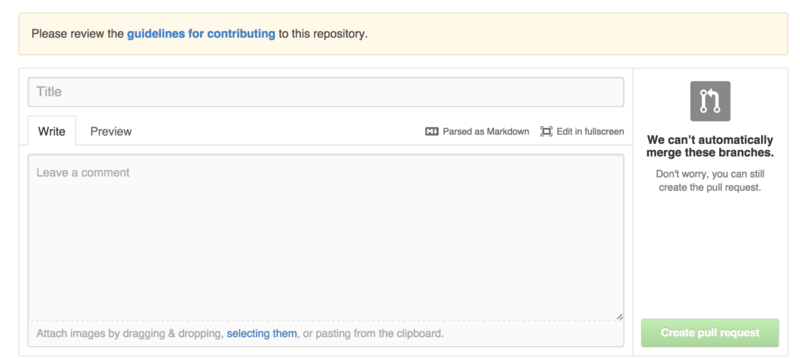

If we click that green button, we’ll see a screen that asks us to give our Pull Request a title and description. It is almost always worthwhile to put some effort into this, since a good description helps the owner of the original project determine what you were trying to do, whether your proposed changes are correct, and whether accepting the changes would improve the original project.

We also see a list of the commits in our topic branch that are “ahead” of the master branch (in this case, just the one) and a unified diff of all the changes that will be made should this branch get merged by the project owner.

When you hit the Create pull request button on this screen, the owner of the project you forked will get a notification that someone is suggesting a change and will link to a page that has all of this information on it.

Note

Though Pull Requests are used commonly for public projects like this when the contributor has a complete change ready to be made, it’s also often used in internal projects at the beginning of the development cycle. Since you can keep pushing to the topic branch even after the Pull Request is opened, it’s often opened early and used as a way to iterate on work as a team within a context, rather than opened at the very end of the process.

Iterating on a Pull Request

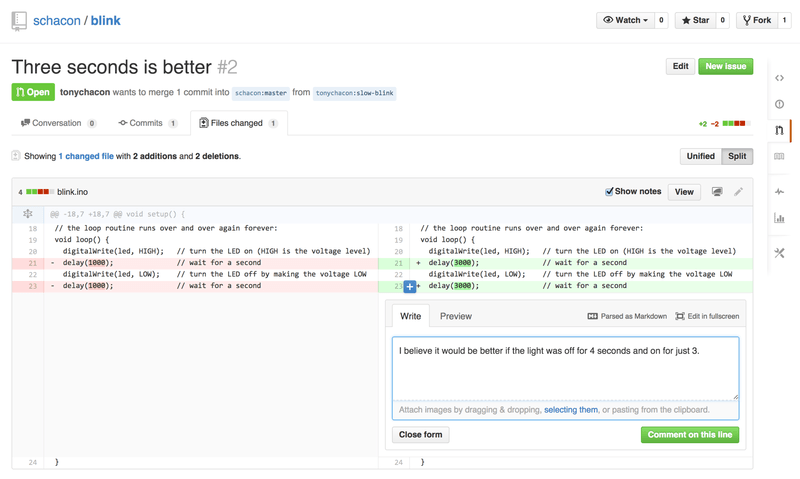

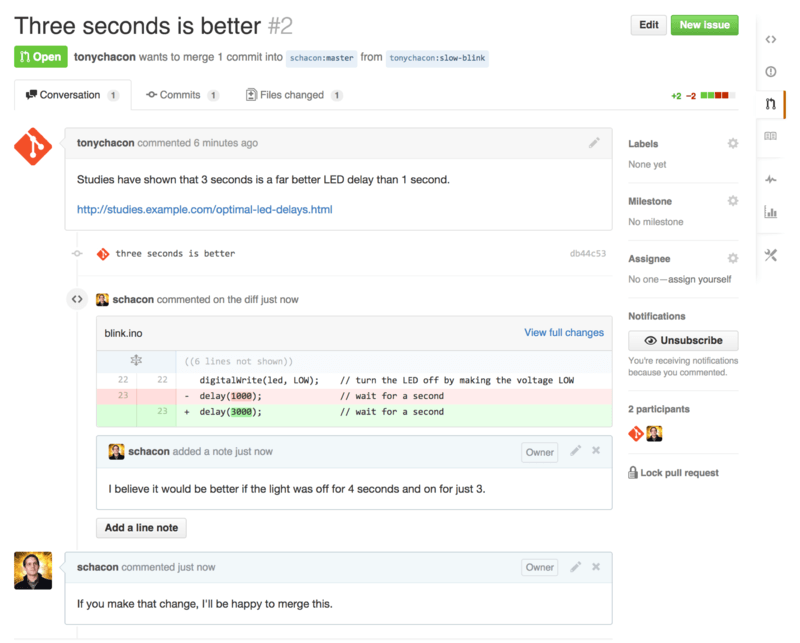

At this point, the project owner can look at the suggested change and merge it, reject it or comment on it. Let’s say that he likes the idea, but would prefer a slightly longer time for the light to be off than on.

Where this conversation may take place over email in the workflows presented in Distributed Git, on GitHub this happens online. The project owner can review the unified diff and leave a comment by clicking on any of the lines.

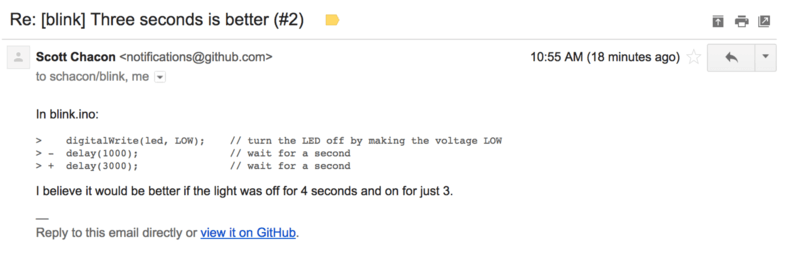

Once the maintainer makes this comment, the person who opened the Pull Request (and indeed, anyone else watching the repository) will get a notification. We’ll go over customizing this later, but if he had email notifications turned on, Tony would get an email like this:

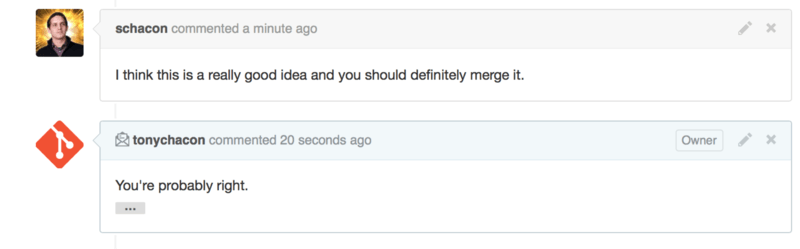

Anyone can also leave general comments on the Pull Request. In Figure 6-14 we can see an example of the project owner both commenting on a line of code and then leaving a general comment in the discussion section. You can see that the code comments are brought into the conversation as well.

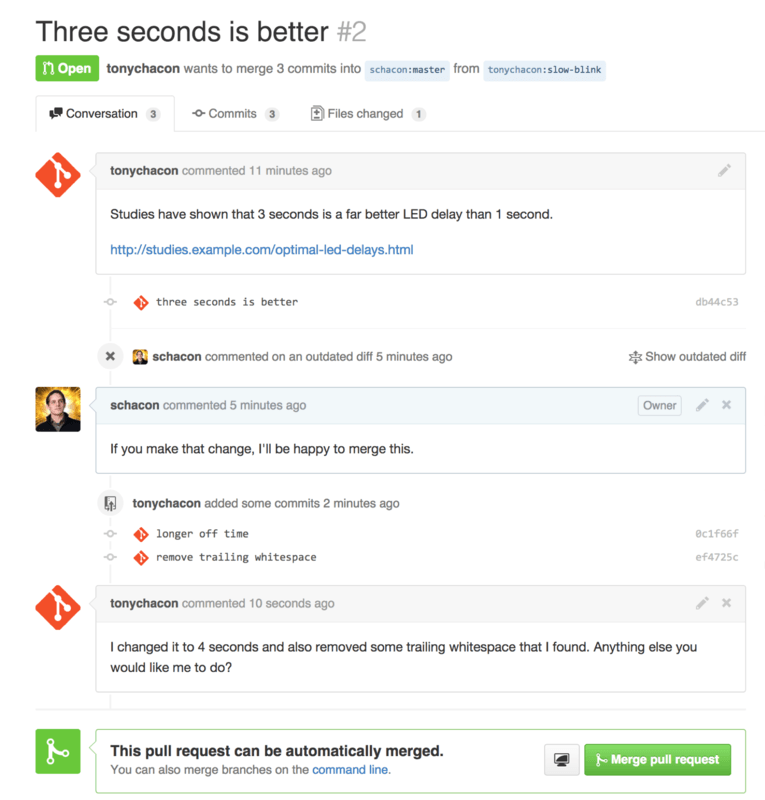

Now the contributor can see what they need to do in order to get their change accepted. Luckily this is very straightforward. Where over email you may have to re-roll your series and resubmit it to the mailing list, with GitHub you simply commit to the topic branch again and push, which will automatically update the Pull Request. In Figure 6-15 you can also see that the old code comment has been collapsed in the updated Pull Request, since it was made on a line that has since been changed.

Adding commits to an existing Pull Request doesn’t trigger a notification, so once Tony has pushed his corrections he decides to leave a comment to inform the project owner that he made the requested change.

An interesting thing to notice is that if you click on the “Files Changed” tab on this Pull Request, you’ll get the “unified” diff — that is, the total aggregate difference that would be introduced to your main branch if this topic branch was merged in. In git diff terms, it basically automatically shows you git diff master...<branch> for the branch this Pull Request is based on. See Determining What Is Introduced for more about this type of diff.

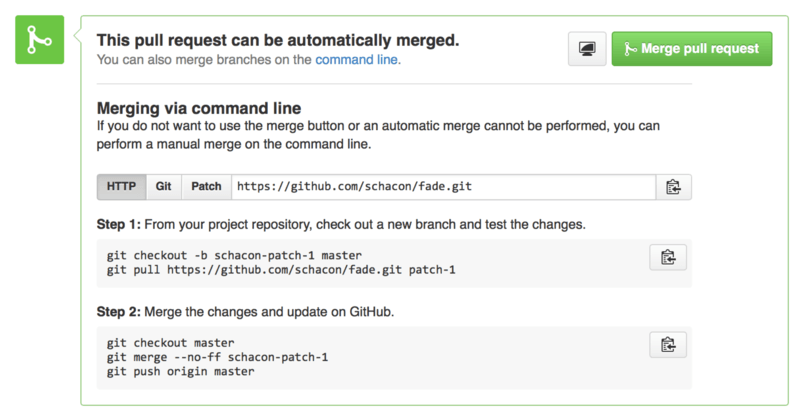

The other thing you’ll notice is that GitHub checks to see if the Pull Request merges cleanly and provides a button to do the merge for you on the server. This button only shows up if you have write access to the repository and a trivial merge is possible. If you click it GitHub will perform a “non-fast-forward” merge, meaning that even if the merge could be a fast-forward, it will still create a merge commit.

If you would prefer, you can simply pull the branch down and merge it locally. If you merge this branch into the master branch and push it to GitHub, the Pull Request will automatically be closed.

This is the basic workflow that most GitHub projects use. Topic branches are created, Pull Requests are opened on them, a discussion ensues, possibly more work is done on the branch and eventually the request is either closed or merged.

Note

Not Only Forks

It’s important to note that you can also open a Pull Request between two branches in the same repository. If you’re working on a feature with someone and you both have write access to the project, you can push a topic branch to the repository and open a Pull Request on it to the master branch of that same project to initiate the code review and discussion process. No forking necessary.

Advanced Pull Requests

Now that we’ve covered the basics of contributing to a project on GitHub, let’s cover a few interesting tips and tricks about Pull Requests so you can be more effective in using them.

Pull Requests as Patches

It’s important to understand that many projects don’t really think of Pull Requests as queues of perfect patches that should apply cleanly in order, as most mailing list-based projects think of patch series contributions. Most GitHub projects think about Pull Request branches as iterative conversations around a proposed change, culminating in a unified diff that is applied by merging.

This is an important distinction, because generally the change is suggested before the code is thought to be perfect, which is far more rare with mailing list based patch series contributions. This enables an earlier conversation with the maintainers so that arriving at the proper solution is more of a community effort. When code is proposed with a Pull Request and the maintainers or community suggest a change, the patch series is generally not re-rolled, but instead the difference is pushed as a new commit to the branch, moving the conversation forward with the context of the previous work intact.

For instance, if you go back and look again at Figure 6-15, you’ll notice that the contributor did not rebase his commit and send another Pull Request. Instead they added new commits and pushed them to the existing branch. This way if you go back and look at this Pull Request in the future, you can easily find all of the context of why decisions were made. Pushing the “Merge” button on the site purposefully creates a merge commit that references the Pull Request so that it’s easy to go back and research the original conversation if necessary.

Keeping up with Upstream

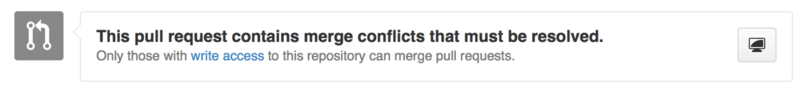

If your Pull Request becomes out of date or otherwise doesn’t merge cleanly, you will want to fix it so the maintainer can easily merge it. GitHub will test this for you and let you know at the bottom of every Pull Request if the merge is trivial or not.

If you see something like Figure 6-16, you’ll want to fix your branch so that it turns green and the maintainer doesn’t have to do extra work.

You have two main options in order to do this. You can either rebase your branch on top of whatever the target branch is (normally the master branch of the repository you forked), or you can merge the target branch into your branch.

Most developers on GitHub will choose to do the latter, for the same reasons we just went over in the previous section. What matters is the history and the final merge, so rebasing isn’t getting you much other than a slightly cleaner history and in return is far more difficult and error prone.

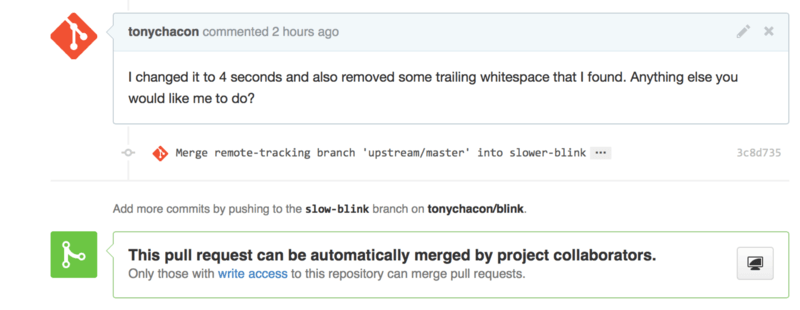

If you want to merge in the target branch to make your Pull Request mergeable, you would add the original repository as a new remote, fetch from it, merge the main branch of that repository into your topic branch, fix any issues and finally push it back up to the same branch you opened the Pull Request on.

For example, let’s say that in the “tonychacon” example we were using before, the original author made a change that would create a conflict in the Pull Request. Let’s go through those steps.

$ git remote add upstream https://github.com/schacon/blink$ git fetch upstream

remote: Counting objects: 3, done. remote: Compressing objects: 100% (3/3), done. Unpacking objects: 100% (3/3), done. remote: Total 3 (delta 0), reused 0 (delta 0) From https://github.com/schacon/blink * [new branch] master -> upstream/master $ git merge upstream/master

Auto-merging blink.ino CONFLICT (content): Merge conflict in blink.ino Automatic merge failed; fix conflicts and then commit the result. $ vim blink.ino

$ git add blink.ino $ git commit [slow-blink 3c8d735] Merge remote-tracking branch 'upstream/master' \ into slower-blink $ git push origin slow-blink

Counting objects: 6, done. Delta compression using up to 8 threads. Compressing objects: 100% (6/6), done. Writing objects: 100% (6/6), 682 bytes | 0 bytes/s, done. Total 6 (delta 2), reused 0 (delta 0) To https://github.com/tonychacon/blink ef4725c..3c8d735 slower-blink -> slow-blink

Add the original repository as a remote named “upstream”

Fetch the newest work from that remote

Merge the main branch into your topic branch

Fix the conflict that occurred

Push back up to the same topic branch

Once you do that, the Pull Request will be automatically updated and re-checked to see if it merges cleanly.

One of the great things about Git is that you can do that continuously. If you have a very long-running project, you can easily merge from the target branch over and over again and only have to deal with conflicts that have arisen since the last time that you merged, making the process very manageable.

If you absolutely wish to rebase the branch to clean it up, you can certainly do so, but it is highly encouraged to not force push over the branch that the Pull Request is already opened on. If other people have pulled it down and done more work on it, you run into all of the issues outlined in The Perils of Rebasing. Instead, push the rebased branch to a new branch on GitHub and open a brand new Pull Request referencing the old one, then close the original.

References

Your next question may be “How do I reference the old Pull Request?”. It turns out there are many, many ways to reference other things almost anywhere you can write in GitHub.

Let’s start with how to cross-reference another Pull Request or an Issue. All Pull Requests and Issues are assigned numbers and they are unique within the project. For example, you can’t have Pull Request #3 and Issue #3. If you want to reference any Pull Request or Issue from any other one, you can simply put #<num> in any comment or description. You can also be more specific if the Issue or Pull request lives somewhere else; write username#<num> if you’re referring to an Issue or Pull Request in a fork of the repository you’re in, or username/repo#<num> to reference something in another repository.

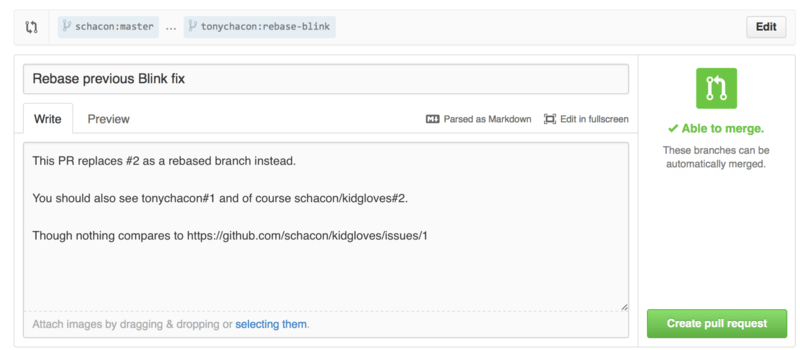

Let’s look at an example. Say we rebased the branch in the previous example, created a new pull request for it, and now we want to reference the old pull request from the new one. We also want to reference an issue in the fork of the repository and an issue in a completely different project. We can fill out the description just like Figure 6-18.

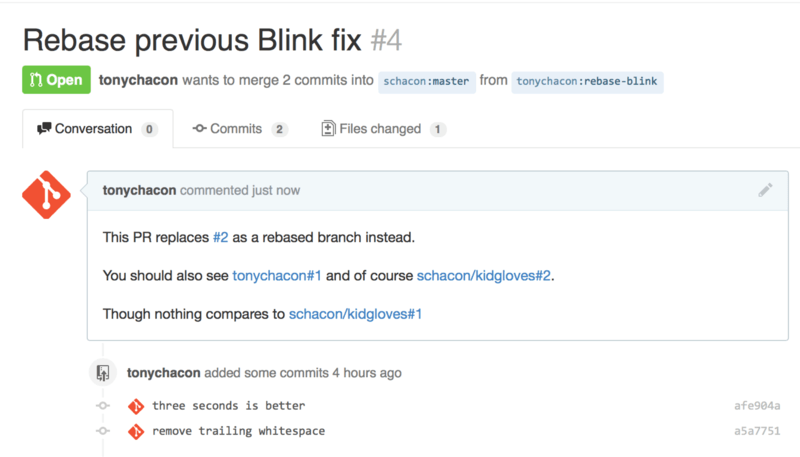

When we submit this pull request, we’ll see all of that rendered like Figure 6-19.

Notice that the full GitHub URL we put in there was shortened to just the information needed.

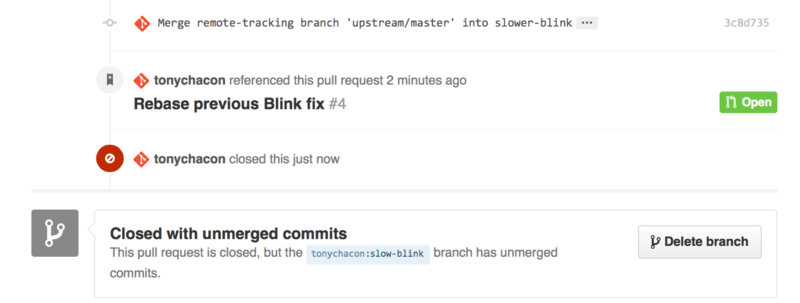

Now if Tony goes back and closes out the original Pull Request, we can see that by mentioning it in the new one, GitHub has automatically created a trackback event in the Pull Request timeline. This means that anyone who visits this Pull Request and sees that it is closed can easily link back to the one that superseded it. The link will look something like Figure 6-20.

In addition to issue numbers, you can also reference a specific commit by SHA-1. You have to specify a full 40 character SHA-1, but if GitHub sees that in a comment, it will link directly to the commit. Again, you can reference commits in forks or other repositories in the same way you did with issues.

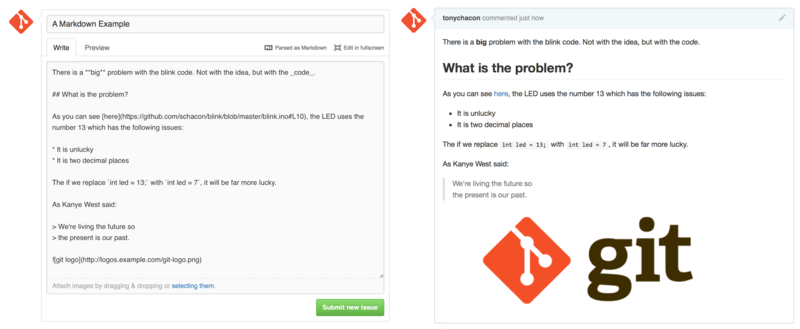

Markdown

Linking to other Issues is just the beginning of interesting things you can do with almost any text box on GitHub. In Issue and Pull Request descriptions, comments, code comments and more, you can use what is called “GitHub Flavored Markdown”. Markdown is like writing in plain text but which is rendered richly.

See Figure 6-21 for an example of how comments or text can be written and then rendered using Markdown.

GitHub Flavored Markdown

The GitHub flavor of Markdown adds more things you can do beyond the basic Markdown syntax. These can all be really useful when creating useful Pull Request or Issue comments or descriptions.

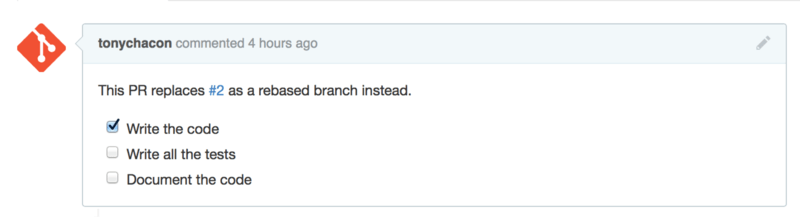

Task Lists

The first really useful GitHub specific Markdown feature, especially for use in Pull Requests, is the Task List. A task list is a list of checkboxes of things you want to get done. Putting them into an Issue or Pull Request normally indicates things that you want to get done before you consider the item complete.

You can create a task list like this:

- [X] Write the code - [ ] Write all the tests - [ ] Document the code

If we include this in the description of our Pull Request or Issue, we’ll see it rendered like Figure 6-22

This is often used in Pull Requests to indicate what all you would like to get done on the branch before the Pull Request will be ready to merge. The really cool part is that you can simply click the checkboxes to update the comment — you don’t have to edit the Markdown directly to check tasks off.

What’s more, GitHub will look for task lists in your Issues and Pull Requests and show them as metadata on the pages that list them out. For example, if you have a Pull Request with tasks and you look at the overview page of all Pull Requests, you can see how far done it is. This helps people break down Pull Requests into subtasks and helps other people track the progress of the branch. You can see an example of this in Figure 6-23.

These are incredibly useful when you open a Pull Request early and use it to track your progress through the implementation of the feature.

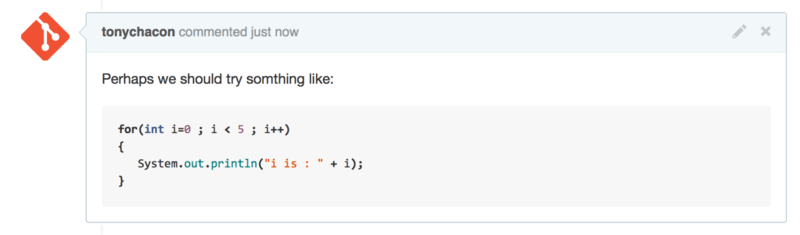

Code Snippets

You can also add code snippets to comments. This is especially useful if you want to present something that you could try to do before actually implementing it as a commit on your branch. This is also often used to add example code of what is not working or what this Pull Request could implement.

To add a snippet of code you have to “fence” it in backticks.

```java

for(int i=0 ; i < 5 ; i++)

{

System.out.println("i is : " + i);

}

```

If you add a language name like we did there with java, GitHub will also try to syntax highlight the snippet. In the case of the above example, it would end up rendering like Figure 6-24.

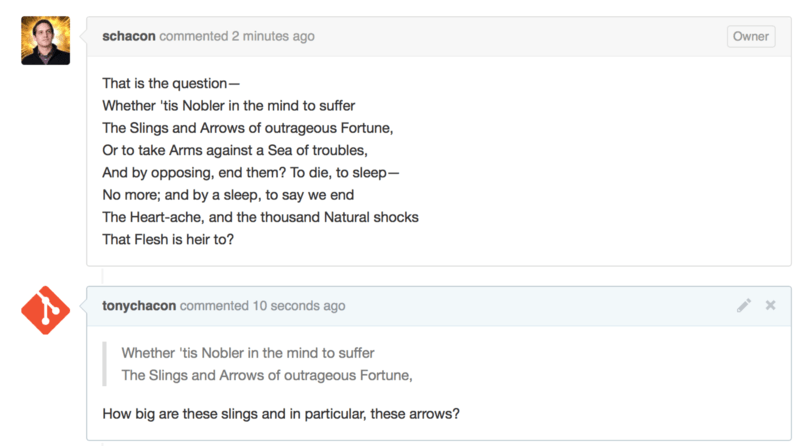

Quoting

If you’re responding to a small part of a long comment, you can selectively quote out of the other comment by preceding the lines with the > character. In fact, this is so common and so useful that there is a keyboard shortcut for it. If you highlight text in a comment that you want to directly reply to and hit the r key, it will quote that text in the comment box for you.

The quotes look something like this:

> Whether 'tis Nobler in the mind to suffer > The Slings and Arrows of outrageous Fortune, How big are these slings and in particular, these arrows?

Once rendered, the comment will look like Figure 6-25.

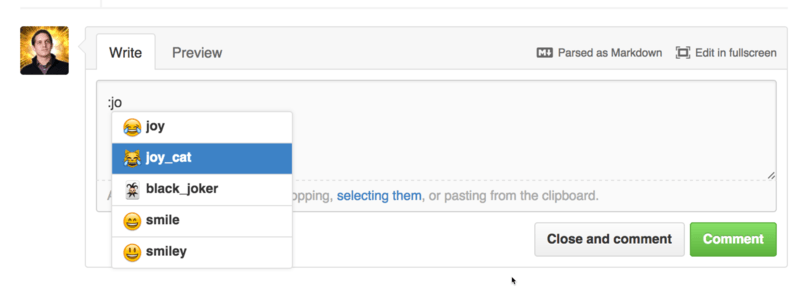

Emoji

Finally, you can also use emoji in your comments. This is actually used quite extensively in comments you see on many GitHub Issues and Pull Requests. There is even an emoji helper in GitHub. If you are typing a comment and you start with a : character, an autocompleter will help you find what you’re looking for.

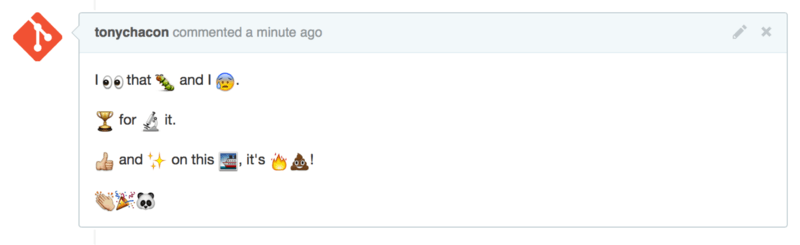

Emojis take the form of :<name>: anywhere in the comment. For instance, you could write something like this:

I :eyes: that :bug: and I :cold_sweat:. :trophy: for :microscope: it. :+1: and :sparkles: on this :ship:, it's :fire::poop:! :clap::tada::panda_face:

When rendered, it would look something like Figure 6-27.

Not that this is incredibly useful, but it does add an element of fun and emotion to a medium that is otherwise hard to convey emotion in.

Note

There are actually quite a number of web services that make use of emoji characters these days. A great cheat sheet to reference to find emoji that expresses what you want to say can be found at:

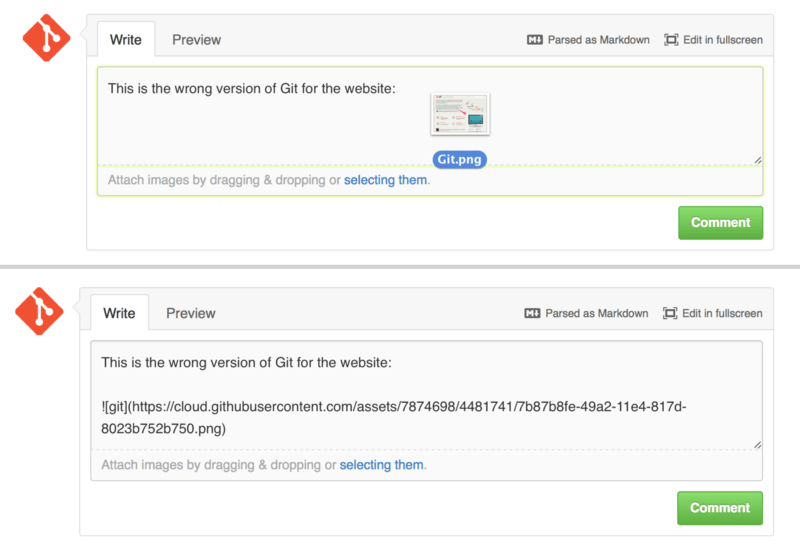

Images

This isn’t technically GitHub Flavored Markdown, but it is incredibly useful. In addition to adding Markdown image links to comments, which can be difficult to find and embed URLs for, GitHub allows you to drag and drop images into text areas to embed them.

If you look back at Figure 6-18, you can see a small “Parsed as Markdown” hint above the text area. Clicking on that will give you a full cheat sheet of everything you can do with Markdown on GitHub.

Maintaining a Project

Now that we’re comfortable contributing to a project, let’s look at the other side: creating, maintaining and administering your own project.

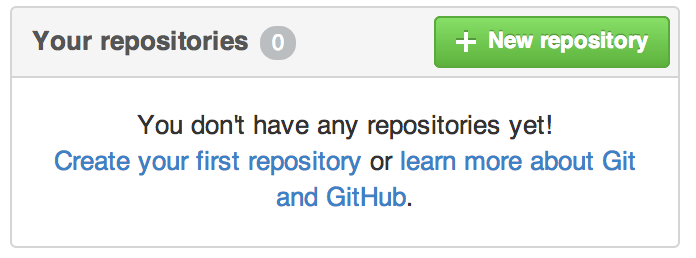

Creating a New Repository

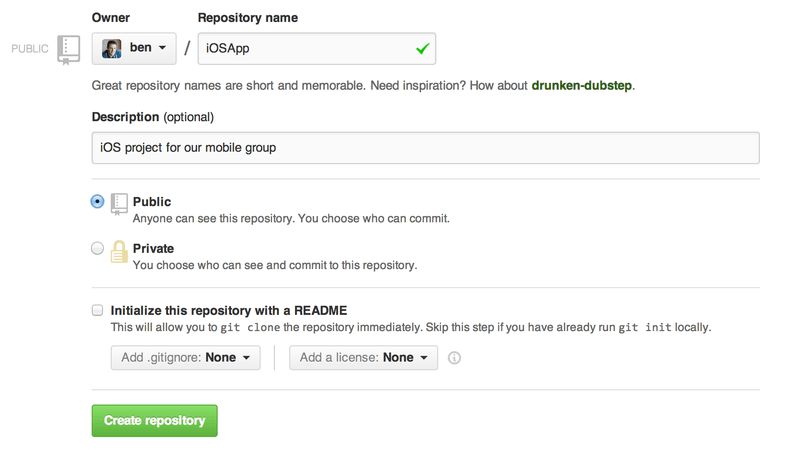

Let’s create a new repository to share our project code with.

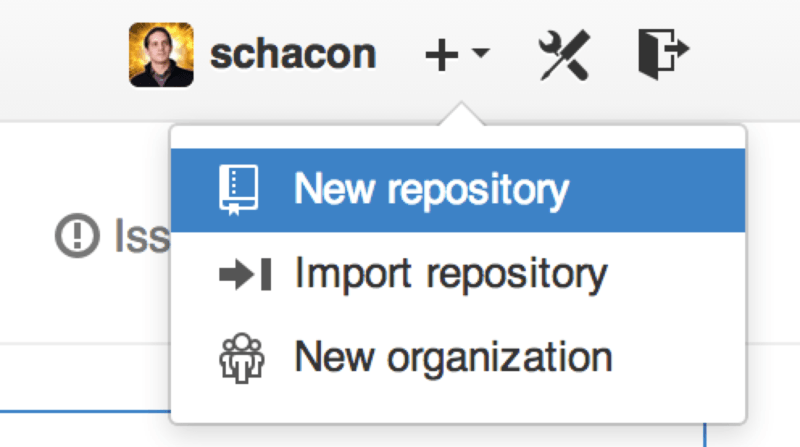

Start by clicking the “New repository” button on the right-hand side of the dashboard, or from the + button in the top toolbar next to your username as seen in Figure 6-30.

This takes you to the “new repository” form:

All you really have to do here is provide a project name; the rest of the fields are completely optional.

For now, just click the “Create Repository” button, and boom – you have a new repository on GitHub, named <user>/<project_name>.

Since you have no code there yet, GitHub will show you instructions for how to create a brand-new Git repository, or connect an existing Git project. We won’t belabor this here; if you need a refresher, check out Git Basics.

Now that your project is hosted on GitHub, you can give the URL to anyone you want to share your project with.

Every project on GitHub is accessible over HTTP as https://github.com/<user>/<project_name>, and over SSH as git@github.com:<user>/<project_name>.

Git can fetch from and push to both of these URLs, but they are access-controlled based on the credentials of the user connecting to them.

Note

It is often preferable to share the HTTP based URL for a public project, since the user does not have to have a GitHub account to access it for cloning. Users will have to have an account and an uploaded SSH key to access your project if you give them the SSH URL. The HTTP one is also exactly the same URL they would paste into a browser to view the project there.

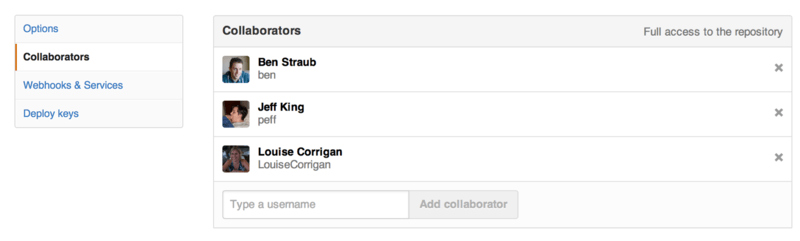

Adding Collaborators

If you’re working with other people who you want to give commit access to, you need to add them as “collaborators”. If Ben, Jeff, and Louise all sign up for accounts on GitHub, and you want to give them push access to your repository, you can add them to your project. Doing so will give them “push” access, which means they have both read and write access to the project and Git repository.

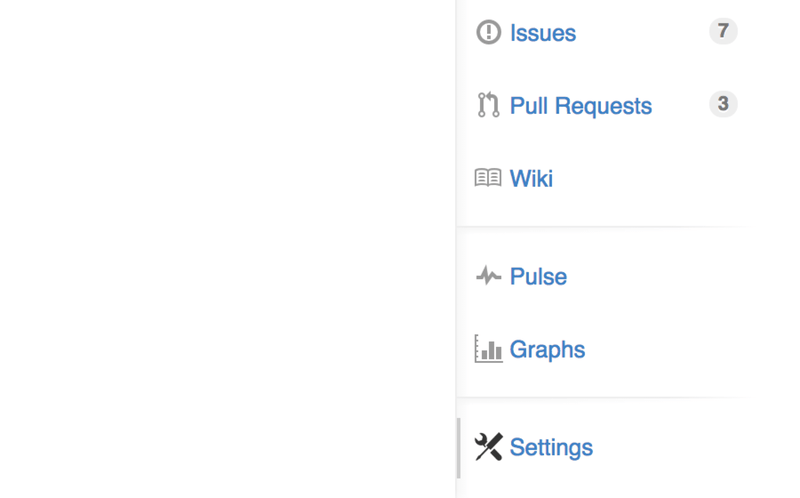

Click the “Settings” link at the bottom of the right-hand sidebar.

Then select “Collaborators” from the menu on the left-hand side. Then, just type a username into the box, and click “Add collaborator.” You can repeat this as many times as you like to grant access to everyone you like. If you need to revoke access, just click the “X” on the right-hand side of their row.

Managing Pull Requests

Now that you have a project with some code in it and maybe even a few collaborators who also have push access, let’s go over what to do when you get a Pull Request yourself.

Pull Requests can either come from a branch in a fork of your repository or they can come from another branch in the same repository. The only difference is that the ones in a fork are often from people where you can’t push to their branch and they can’t push to yours, whereas with internal Pull Requests generally both parties can access the branch.

For these examples, let’s assume you are “tonychacon” and you’ve created a new Arduino code project named “fade”.

Email Notifications

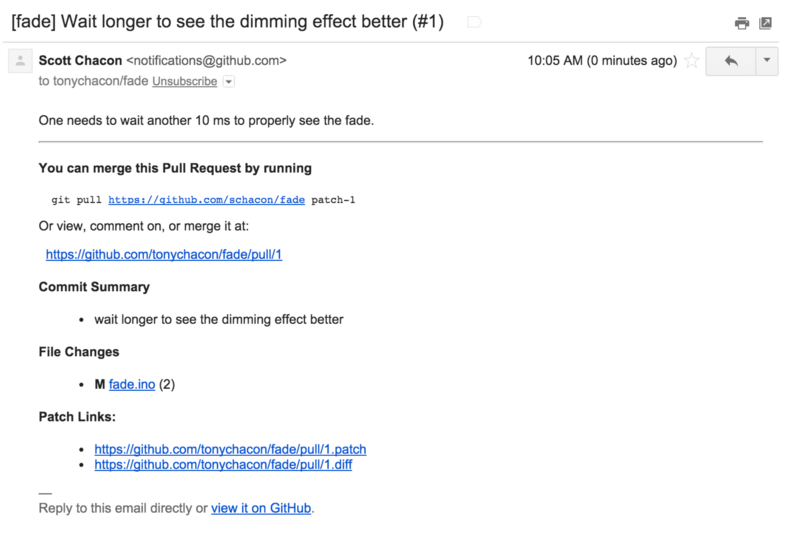

Someone comes along and makes a change to your code and sends you a Pull Request. You should get an email notifying you about the new Pull Request and it should look something like Figure 6-34.

There are a few things to notice about this email. It will give you a small diffstat — a list of files that have changed in the Pull Request and by how much. It gives you a link to the Pull Request on GitHub. It also gives you a few URLs that you can use from the command line.

If you notice the line that says git pull <url> patch-1, this is a simple way to merge in a remote branch without having to add a remote.

We went over this quickly in Checking Out Remote Branches.

If you wish, you can create and switch to a topic branch and then run this command to merge in the Pull Request changes.

The other interesting URLs are the .diff and .patch URLs, which as you may guess, provide unified diff and patch versions of the Pull Request.

You could technically merge in the Pull Request work with something like this:

$ curl http://github.com/tonychacon/fade/pull/1.patch | git am

Collaborating on the Pull Request

As we covered in The GitHub Flow, you can now have a conversation with the person who opened the Pull Request. You can comment on specific lines of code, comment on whole commits or comment on the entire Pull Request itself, using GitHub Flavored Markdown everywhere.

Every time someone else comments on the Pull Request you will continue to get email notifications so you know there is activity happening. They will each have a link to the Pull Request where the activity is happening and you can also directly respond to the email to comment on the Pull Request thread.

Once the code is in a place you like and want to merge it in, you can either pull the code down and merge it locally, either with the git pull <url> <branch> syntax we saw earlier, or by adding the fork as a remote and fetching and merging.

If the merge is trivial, you can also just hit the “Merge” button on the GitHub site. This will do a “non-fast-forward” merge, creating a merge commit even if a fast-forward merge was possible. This means that no matter what, every time you hit the merge button, a merge commit is created. As you can see in Figure 6-36, GitHub gives you all of this information if you click the hint link.

If you decide you don’t want to merge it, you can also just close the Pull Request and the person who opened it will be notified.

Pull Request Refs

If you’re dealing with a lot of Pull Requests and don’t want to add a bunch of remotes or do one time pulls every time, there is a neat trick that GitHub allows you to do. This is a bit of an advanced trick and we’ll go over the details of this a bit more in The Refspec, but it can be pretty useful.

GitHub actually advertises the Pull Request branches for a repository as sort of pseudo-branches on the server. By default you don’t get them when you clone, but they are there in an obscured way and you can access them pretty easily.

To demonstrate this, we’re going to use a low-level command (often referred to as a “plumbing” command, which we’ll read about more in Plumbing and Porcelain) called ls-remote.

This command is generally not used in day-to-day Git operations but it’s useful to show us what references are present on the server.

If we run this command against the “blink” repository we were using earlier, we will get a list of all the branches and tags and other references in the repository.

$ git ls-remote https://github.com/schacon/blink 10d539600d86723087810ec636870a504f4fee4d HEAD 10d539600d86723087810ec636870a504f4fee4d refs/heads/master 6a83107c62950be9453aac297bb0193fd743cd6e refs/pull/1/head afe83c2d1a70674c9505cc1d8b7d380d5e076ed3 refs/pull/1/merge 3c8d735ee16296c242be7a9742ebfbc2665adec1 refs/pull/2/head 15c9f4f80973a2758462ab2066b6ad9fe8dcf03d refs/pull/2/merge a5a7751a33b7e86c5e9bb07b26001bb17d775d1a refs/pull/4/head 31a45fc257e8433c8d8804e3e848cf61c9d3166c refs/pull/4/merge

Of course, if you’re in your repository and you run git ls-remote origin or whatever remote you want to check, it will show you something similar to this.

If the repository is on GitHub and you have any Pull Requests that have been opened, you’ll get these references that are prefixed with refs/pull/.

These are basically branches, but since they’re not under refs/heads/ you don’t get them normally when you clone or fetch from the server — the process of fetching ignores them normally.

There are two references per Pull Request - the one that ends in /head points to exactly the same commit as the last commit in the Pull Request branch.

So if someone opens a Pull Request in our repository and their branch is named bug-fix and it points to commit a5a775, then in our repository we will not have a bug-fix branch (since that’s in their fork), but we will have pull/<pr#>/head that points to a5a775.

This means that we can pretty easily pull down every Pull Request branch in one go without having to add a bunch of remotes.

Now, you could do something like fetching the reference directly.

$ git fetch origin refs/pull/958/head From https://github.com/libgit2/libgit2 * branch refs/pull/958/head -> FETCH_HEAD

This tells Git, “Connect to the origin remote, and download the ref named refs/pull/958/head.”

Git happily obeys, and downloads everything you need to construct that ref, and puts a pointer to the commit you want under .git/FETCH_HEAD.

You can follow that up with git merge FETCH_HEAD into a branch you want to test it in, but that merge commit message looks a bit weird.

Also, if you’re reviewing a lot of pull requests, this gets tedious.

There’s also a way to fetch all of the pull requests, and keep them up to date whenever you connect to the remote.

Open up .git/config in your favorite editor, and look for the origin remote.

It should look a bit like this:

[remote "origin"]

url = https://github.com/libgit2/libgit2

fetch = +refs/heads/*:refs/remotes/origin/*

That line that begins with fetch = is a “refspec.”

It’s a way of mapping names on the remote with names in your local .git directory.

This particular one tells Git, "the things on the remote that are under refs/heads should go in my local repository under refs/remotes/origin."

You can modify this section to add another refspec:

[remote "origin"]

url = https://github.com/libgit2/libgit2.git

fetch = +refs/heads/*:refs/remotes/origin/*

fetch = +refs/pull/*/head:refs/remotes/origin/pr/*

That last line tells Git, “All the refs that look like refs/pull/123/head should be stored locally like refs/remotes/origin/pr/123.”

Now, if you save that file, and do a git fetch:

$ git fetch # … * [new ref] refs/pull/1/head -> origin/pr/1 * [new ref] refs/pull/2/head -> origin/pr/2 * [new ref] refs/pull/4/head -> origin/pr/4 # …

Now all of the remote pull requests are represented locally with refs that act much like tracking branches; they’re read-only, and they update when you do a fetch. This makes it super easy to try the code from a pull request locally:

$ git checkout pr/2 Checking out files: 100% (3769/3769), done. Branch pr/2 set up to track remote branch pr/2 from origin. Switched to a new branch 'pr/2'

The eagle-eyed among you would note the head on the end of the remote portion of the refspec.

There’s also a refs/pull/#/merge ref on the GitHub side, which represents the commit that would result if you push the “merge” button on the site.

This can allow you to test the merge before even hitting the button.

Pull Requests on Pull Requests

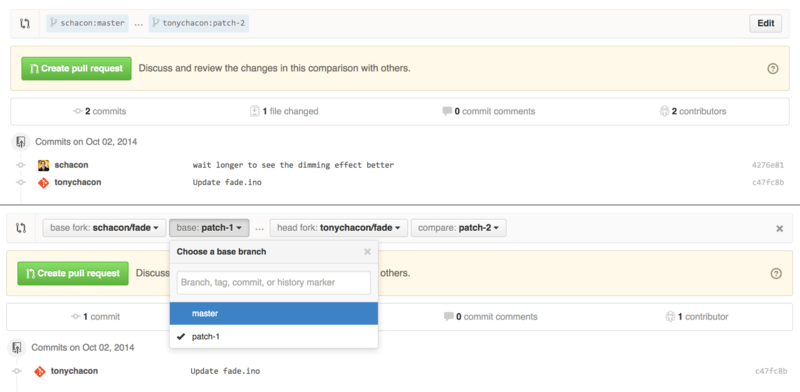

Not only can you open Pull Requests that target the main or master branch, you can actually open a Pull Request targeting any branch in the network.

In fact, you can even target another Pull Request.

If you see a Pull Request that is moving in the right direction and you have an idea for a change that depends on it or you’re not sure is a good idea, or you just don’t have push access to the target branch, you can open a Pull Request directly to it.

When you go to open a Pull Request, there is a box at the top of the page that specifies which branch you’re requesting to pull to and which you’re requesting to pull from. If you hit the “Edit” button at the right of that box you can change not only the branches but also which fork.

Here you can fairly easily specify to merge your new branch into another Pull Request or another fork of the project.

Mentions and Notifications

GitHub also has a pretty nice notifications system built in that can come in handy when you have questions or need feedback from specific individuals or teams.

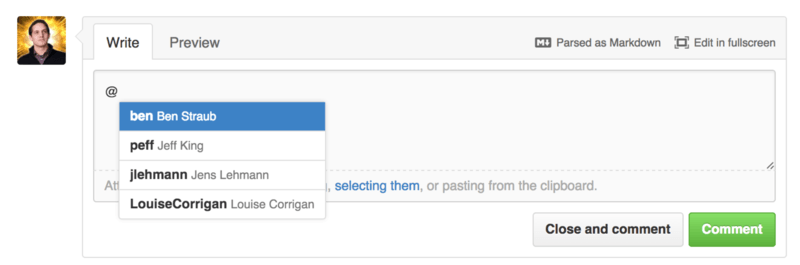

In any comment you can start typing a @ character and it will begin to autocomplete with the names and usernames of people who are collaborators or contributors in the project.

You can also mention a user who is not in that dropdown, but often the autocompleter can make it faster.

Once you post a comment with a user mention, that user will be notified. This means that this can be a really effective way of pulling people into conversations rather than making them poll. Very often in Pull Requests on GitHub people will pull in other people on their teams or in their company to review an Issue or Pull Request.

If someone gets mentioned on a Pull Request or Issue, they will be “subscribed” to it and will continue getting notifications any time some activity occurs on it. You will also be subscribed to something if you opened it, if you’re watching the repository or if you comment on something. If you no longer wish to receive notifications, there is an “Unsubscribe” button on the page you can click to stop receiving updates on it.

The Notifications Page

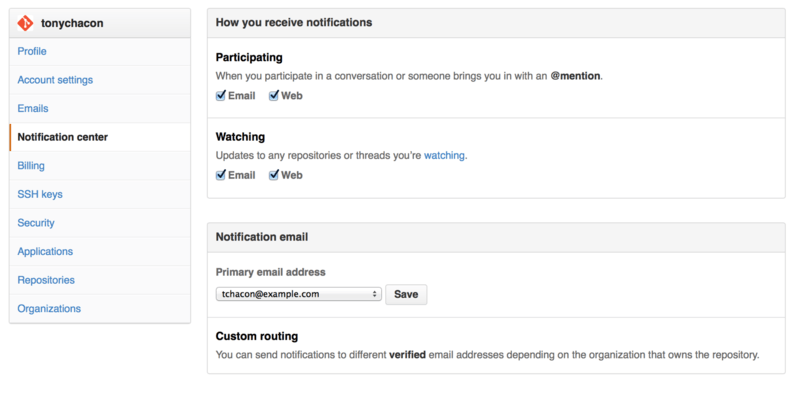

When we mention “notifications” here with respect to GitHub, we mean a specific way that GitHub tries to get in touch with you when events happen and there are a few different ways you can configure them. If you go to the “Notification center” tab from the settings page, you can see some of the options you have.

The two choices are to get notifications over “Email” and over “Web” and you can choose either, neither or both for when you actively participate in things and for activity on repositories you are watching.

Web Notifications

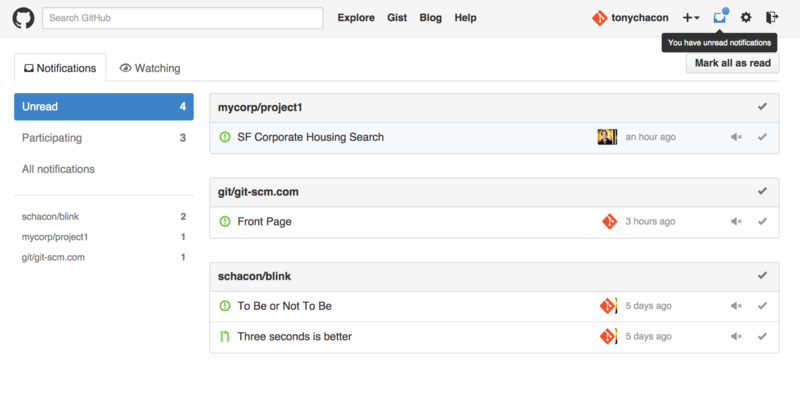

Web notifications only exist on GitHub and you can only check them on GitHub. If you have this option selected in your preferences and a notification is triggered for you, you will see a small blue dot over your notifications icon at the top of your screen as seen in Figure 6-41.

If you click on that, you will see a list of all the items you have been notified about, grouped by project. You can filter to the notifications of a specific project by clicking on its name in the left hand sidebar. You can also acknowledge the notification by clicking the checkmark icon next to any notification, or acknowledge all of the notifications in a project by clicking the checkmark at the top of the group. There is also a mute button next to each checkmark that you can click to not receive any further notifications on that item.

All of these tools are very useful for handling large numbers of notifications. Many GitHub power users will simply turn off email notifications entirely and manage all of their notifications through this screen.

Email Notifications

Email notifications are the other way you can handle notifications through GitHub. If you have this turned on you will get emails for each notification. We saw examples of this in Figure 6-13 and Figure 6-34. The emails will also be threaded properly, which is nice if you’re using a threading email client.

There is also a fair amount of metadata embedded in the headers of the emails that GitHub sends you, which can be really helpful for setting up custom filters and rules.

For instance, if we look at the actual email headers sent to Tony in the email shown in Figure 6-34, we will see the following among the information sent:

To: tonychacon/fade <fade@noreply.github.com> Message-ID: <tonychacon/fade/pull/1@github.com> Subject: [fade] Wait longer to see the dimming effect better (#1) X-GitHub-Recipient: tonychacon List-ID: tonychacon/fade <fade.tonychacon.github.com> List-Archive: https://github.com/tonychacon/fade List-Post: <mailto:reply+i-4XXX@reply.github.com> List-Unsubscribe: <mailto:unsub+i-XXX@reply.github.com>,... X-GitHub-Recipient-Address: tchacon@example.com

There are a couple of interesting things here.

If you want to highlight or re-route emails to this particular project or even Pull Request, the information in Message-ID gives you all the data in <user>/<project>/<type>/<id> format.

If this were an issue, for example, the <type> field would have been “issues” rather than “pull”.

The List-Post and List-Unsubscribe fields mean that if you have a mail client that understands those, you can easily post to the list or “Unsubscribe” from the thread.

That would be essentially the same as clicking the “mute” button on the web version of the notification or “Unsubscribe” on the Issue or Pull Request page itself.

It’s also worth noting that if you have both email and web notifications enabled and you read the email version of the notification, the web version will be marked as read as well if you have images allowed in your mail client.

Special Files

There are a couple of special files that GitHub will notice if they are present in your repository.

README

The first is the README file, which can be of nearly any format that GitHub recognizes as prose.

For example, it could be README, README.md, README.asciidoc, etc.

If GitHub sees a README file in your source, it will render it on the landing page of the project.

Many teams use this file to hold all the relevant project information for someone who might be new to the repository or project. This generally includes things like:

-

What the project is for

-

How to configure and install it

-

An example of how to use it or get it running

-

The license that the project is offered under

-

How to contribute to it

Since GitHub will render this file, you can embed images or links in it for added ease of understanding.

CONTRIBUTING

The other special file that GitHub recognizes is the CONTRIBUTING file.

If you have a file named CONTRIBUTING with any file extension, GitHub will show Figure 6-42 when anyone starts opening a Pull Request.

The idea here is that you can specify specific things you want or don’t want in a Pull Request sent to your project. This way people may actually read the guidelines before opening the Pull Request.

Project Administration

Generally there are not a lot of administrative things you can do with a single project, but there are a couple of items that might be of interest.

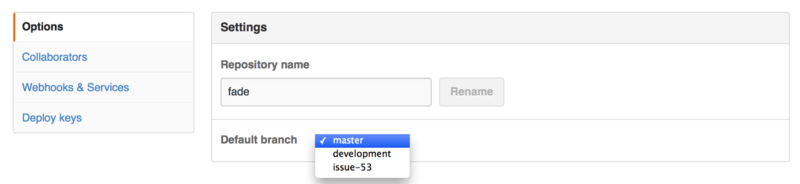

Changing the Default Branch

If you are using a branch other than “master” as your default branch that you want people to open Pull Requests on or see by default, you can change that in your repository’s settings page under the “Options” tab.

Simply change the default branch in the dropdown and that will be the default for all major operations from then on, including which branch is checked out by default when someone clones the repository.

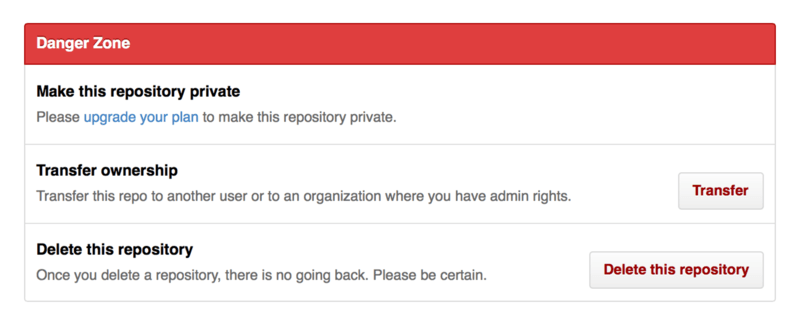

Transferring a Project

If you would like to transfer a project to another user or an organization in GitHub, there is a “Transfer ownership” option at the bottom of the same “Options” tab of your repository settings page that allows you to do this.

This is helpful if you are abandoning a project and someone wants to take it over, or if your project is getting bigger and want to move it into an organization.

Not only does this move the repository along with all its watchers and stars to another place, it also sets up a redirect from your URL to the new place. It will also redirect clones and fetches from Git, not just web requests.

Managing an organization

In addition to single-user accounts, GitHub has what are called Organizations. Like personal accounts, Organizational accounts have a namespace where all their projects exist, but many other things are different. These accounts represent a group of people with shared ownership of projects, and there are many tools to manage subgroups of those people. Normally these accounts are used for Open Source groups (such as “perl” or “rails”) or companies (such as “google” or “twitter”).

Organization Basics

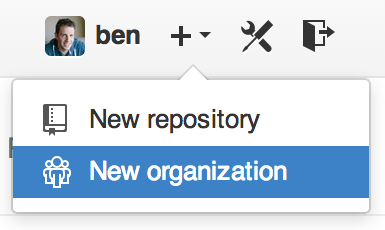

An organization is pretty easy to create; just click on the “+” icon at the top-right of any GitHub page, and select “New organization” from the menu.

First you’ll need to name your organization and provide an email address for a main point of contact for the group. Then you can invite other users to be co-owners of the account if you want to.

Follow these steps and you’ll soon be the owner of a brand-new organization. Like personal accounts, organizations are free if everything you plan to store there will be open source.

As an owner in an organization, when you fork a repository, you’ll have the choice of forking it to your organization’s namespace. When you create new repositories you can create them either under your personal account or under any of the organizations that you are an owner in. You also automatically “watch” any new repository created under these organizations.

Just like in Your Avatar, you can upload an avatar for your organization to personalize it a bit. Also just like personal accounts, you have a landing page for the organization that lists all of your repositories and can be viewed by other people.

Now let’s cover some of the things that are a bit different with an organizational account.

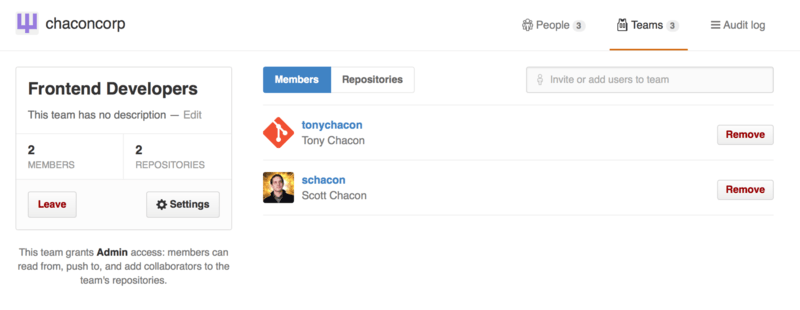

Teams

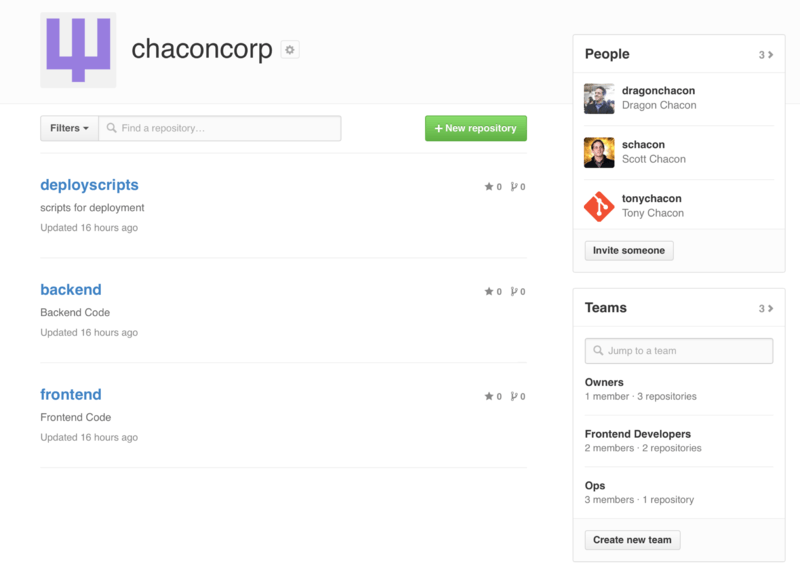

Organizations are associated with individual people by way of teams, which are simply a grouping of individual user accounts and repositories within the organization and what kind of access those people have in those repositories.

For example, say your company has three repositories: frontend, backend, and deployscripts.

You’d want your HTML/CSS/JavaScript developers to have access to frontend and maybe backend, and your Operations people to have access to backend and deployscripts.

Teams make this easy, without having to manage the collaborators for every individual repository.

The Organization page shows you a simple dashboard of all the repositories, users and teams that are under this organization.

To manage your Teams, you can click on the Teams sidebar on the right hand side of the page in Figure 6-46. This will bring you to a page you can use to add members to the team, add repositories to the team or manage the settings and access control levels for the team. Each team can have read only, read/write or administrative access to the repositories. You can change that level by clicking the “Settings” button in Figure 6-47.

When you invite someone to a team, they will get an email letting them know they’ve been invited.

Additionally, team @mentions (such as @acmecorp/frontend) work much the same as they do with individual users, except that all members of the team are then subscribed to the thread.

This is useful if you want the attention from someone on a team, but you don’t know exactly who to ask.

A user can belong to any number of teams, so don’t limit yourself to only access-control teams.

Special-interest teams like ux, css, or refactoring are useful for certain kinds of questions, and others like legal and colorblind for an entirely different kind.

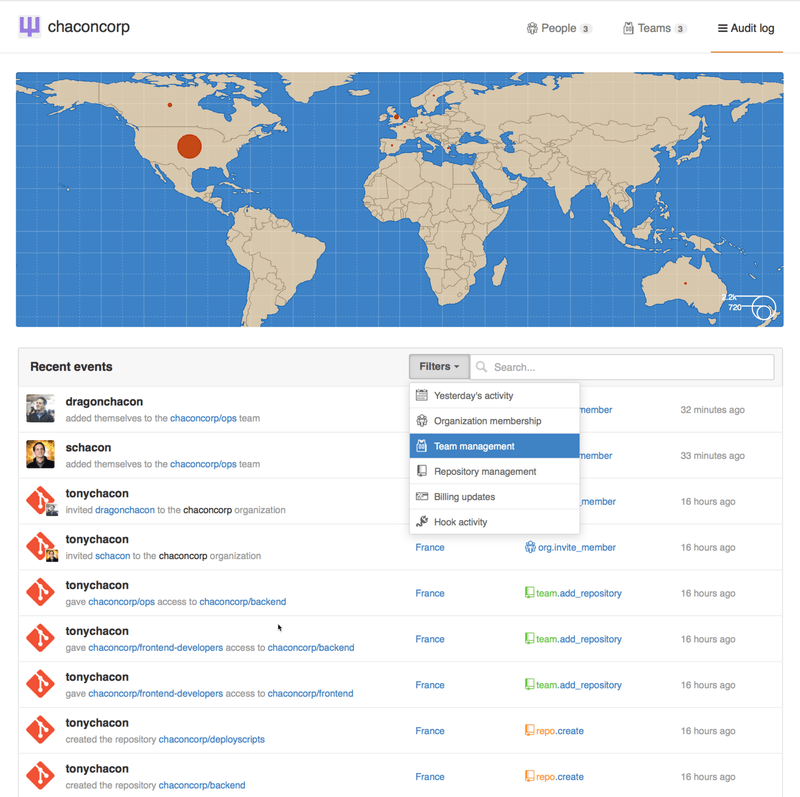

Audit Log

Organizations also give owners access to all the information about what went on under the organization. You can go to the Audit Log tab and see what events have happened at an organization level, who did them and where in the world they were done.

You can also filter down to specific types of events, specific places or specific people.

Scripting GitHub

So now we’ve covered all of the major features and workflows of GitHub, but any large group or project will have customizations they may want to make or external services they may want to integrate.

Luckily for us, GitHub is really quite hackable in many ways. In this section we’ll cover how to use the GitHub hooks system and its API to make GitHub work how we want it to.

Hooks

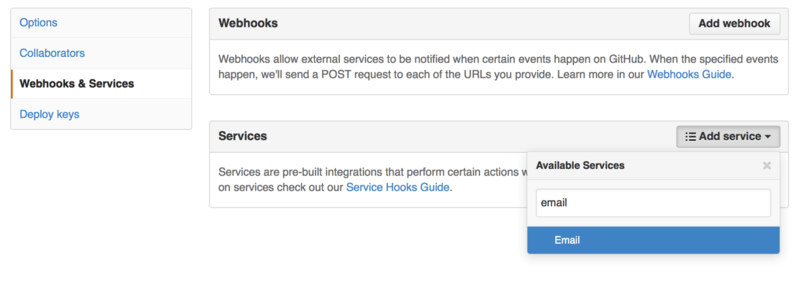

The Hooks and Services section of GitHub repository administration is the easiest way to have GitHub interact with external systems.

Services

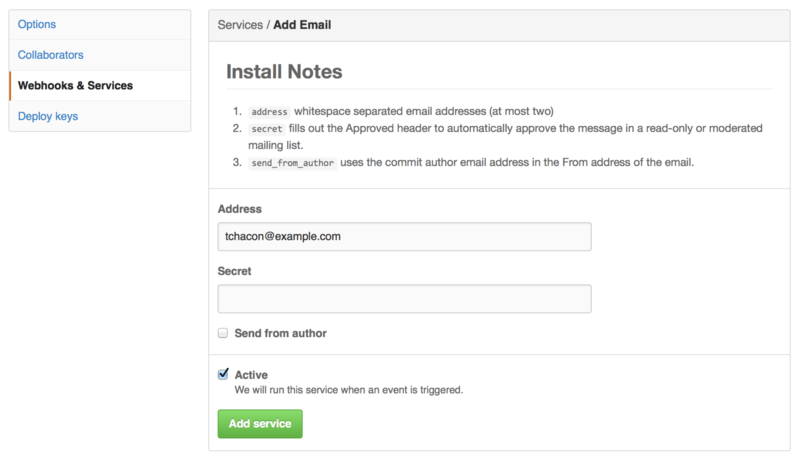

First we’ll take a look at Services. Both the Hooks and Services integrations can be found in the Settings section of your repository, where we previously looked at adding Collaborators and changing the default branch of your project. Under the “Webhooks and Services” tab you will see something like Figure 6-49.

There are dozens of services you can choose from, most of them integrations into other commercial and open source systems. Most of them are for Continuous Integration services, bug and issue trackers, chat room systems and documentation systems. We’ll walk through setting up a very simple one, the Email hook. If you choose “email” from the “Add Service” dropdown, you’ll get a configuration screen like Figure 6-50.

In this case, if we hit the “Add service” button, the email address we specified will get an email every time someone pushes to the repository. Services can listen for lots of different types of events, but most only listen for push events and then do something with that data.

If there is a system you are using that you would like to integrate with GitHub, you should check here to see if there is an existing service integration available. For example, if you’re using Jenkins to run tests on your codebase, you can enable the Jenkins builtin service integration to kick off a test run every time someone pushes to your repository.

Hooks

If you need something more specific or you want to integrate with a service or site that is not included in this list, you can instead use the more generic hooks system. GitHub repository hooks are pretty simple. You specify a URL and GitHub will post an HTTP payload to that URL on any event you want.

Generally the way this works is you can setup a small web service to listen for a GitHub hook payload and then do something with the data when it is received.

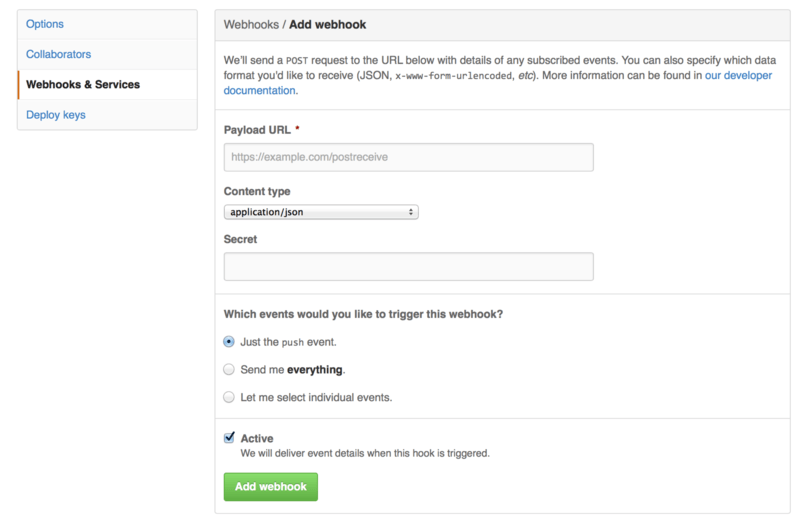

To enable a hook, you click the “Add webhook” button in Figure 6-49. This will bring you to a page that looks like Figure 6-51.

The configuration for a web hook is pretty simple.

In most cases you simply enter a URL and a secret key and hit “Add webhook”.

There are a few options for which events you want GitHub to send you a payload for — the default is to only get a payload for the push event, when someone pushes new code to any branch of your repository.

Let’s see a small example of a web service you may set up to handle a web hook. We’ll use the Ruby web framework Sinatra since it’s fairly concise and you should be able to easily see what we’re doing.

Let’s say we want to get an email if a specific person pushes to a specific branch of our project modifying a specific file. We could fairly easily do that with code like this:

require 'sinatra'

require 'json'

require 'mail'

post '/payload' do

push = JSON.parse(request.body.read) # parse the JSON

# gather the data we're looking for

pusher = push["pusher"]["name"]

branch = push["ref"]

# get a list of all the files touched

files = push["commits"].map do |commit|

commit['added'] + commit['modified'] + commit['removed']

end

files = files.flatten.uniq

# check for our criteria

if pusher == 'schacon' &&

branch == 'ref/heads/special-branch' &&

files.include?('special-file.txt')

Mail.deliver do

from 'tchacon@example.com'

to 'tchacon@example.com'

subject 'Scott Changed the File'

body "ALARM"

end

end

end

Here we’re taking the JSON payload that GitHub delivers us and looking up who pushed it, what branch they pushed to and what files were touched in all the commits that were pushed. Then we check that against our criteria and send an email if it matches.

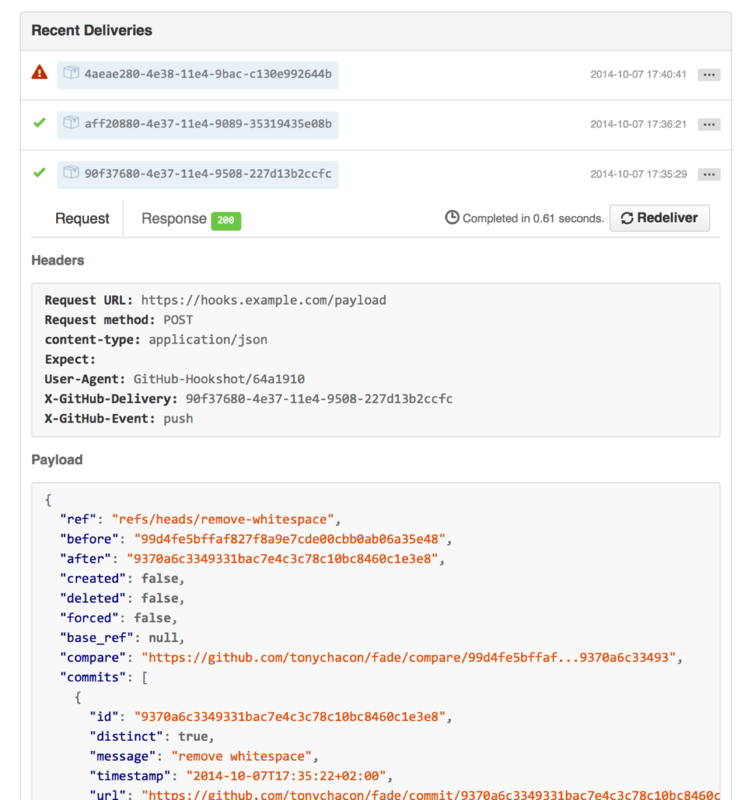

In order to develop and test something like this, you have a nice developer console in the same screen where you set the hook up. You can see the last few deliveries that GitHub has tried to make for that webhook. For each hook you can dig down into when it was delivered, if it was successful and the body and headers for both the request and the response. This makes it incredibly easy to test and debug your hooks.

The other great feature of this is that you can redeliver any of the payloads to test your service easily.

For more information on how to write webhooks and all the different event types you can listen for, go to the GitHub Developer documentation at https://developer.github.com/webhooks/

The GitHub API

Services and hooks give you a way to receive push notifications about events that happen on your repositories, but what if you need more information about these events? What if you need to automate something like adding collaborators or labeling issues?

This is where the GitHub API comes in handy. GitHub has tons of API endpoints for doing nearly anything you can do on the website in an automated fashion. In this section we’ll learn how to authenticate and connect to the API, how to comment on an issue and how to change the status of a Pull Request through the API.

Basic Usage

The most basic thing you can do is a simple GET request on an endpoint that doesn’t require authentication. This could be a user or read-only information on an open source project. For example, if we want to know more about a user named “schacon”, we can run something like this:

$ curl https://api.github.com/users/schacon

{

"login": "schacon",

"id": 70,

"avatar_url": "https://avatars.githubusercontent.com/u/70",

# …

"name": "Scott Chacon",

"company": "GitHub",

"following": 19,

"created_at": "2008-01-27T17:19:28Z",

"updated_at": "2014-06-10T02:37:23Z"

}

There are tons of endpoints like this to get information about organizations, projects, issues, commits — just about anything you can publicly see on GitHub.

You can even use the API to render arbitrary Markdown or find a .gitignore template.

$ curl https://api.github.com/gitignore/templates/Java

{

"name": "Java",

"source": "*.class

# Mobile Tools for Java (J2ME)

.mtj.tmp/

# Package Files #

*.jar

*.war

*.ear

# virtual machine crash logs, see http://www.java.com/en/download/help/error_hotspot.xml

hs_err_pid*

"

}

Commenting on an Issue

However, if you want to do an action on the website such as comment on an Issue or Pull Request or if you want to view or interact with private content, you’ll need to authenticate.

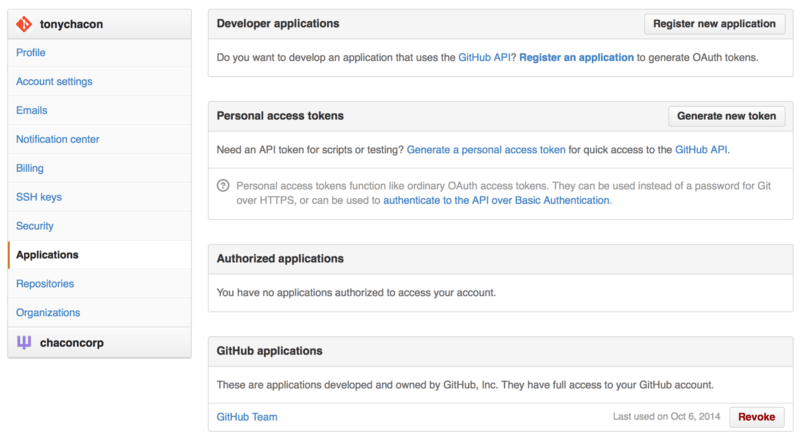

There are several ways to authenticate. You can use basic authentication with just your username and password, but generally it’s a better idea to use a personal access token. You can generate this from the “Applications” tab of your settings page.

It will ask you which scopes you want for this token and a description. Make sure to use a good description so you feel comfortable removing the token when your script or application is no longer used.

GitHub will only show you the token once, so be sure to copy it. You can now use this to authenticate in your script instead of using a username and password. This is nice because you can limit the scope of what you want to do and the token is revocable.

This also has the added advantage of increasing your rate limit. Without authenticating, you will be limited to 60 requests per hour. If you authenticate you can make up to 5,000 requests per hour.

So let’s use it to make a comment on one of our issues.

Let’s say we want to leave a comment on a specific issue, Issue #6.

To do so we have to do an HTTP POST request to repos/<user>/<repo>/issues/<num>/comments with the token we just generated as an Authorization header.

$ curl -H "Content-Type: application/json" \

-H "Authorization: token TOKEN" \

--data '{"body":"A new comment, :+1:"}' \

https://api.github.com/repos/schacon/blink/issues/6/comments

{

"id": 58322100,

"html_url": "https://github.com/schacon/blink/issues/6#issuecomment-58322100",

...

"user": {

"login": "tonychacon",

"id": 7874698,

"avatar_url": "https://avatars.githubusercontent.com/u/7874698?v=2",

"type": "User",

},

"created_at": "2014-10-08T07:48:19Z",

"updated_at": "2014-10-08T07:48:19Z",

"body": "A new comment, :+1:"

}

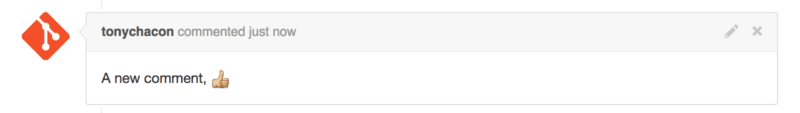

Now if you go to that issue, you can see the comment that we just successfully posted as in Figure 6-54.

You can use the API to do just about anything you can do on the website — creating and setting milestones, assigning people to Issues and Pull Requests, creating and changing labels, accessing commit data, creating new commits and branches, opening, closing or merging Pull Requests, creating and editing teams, commenting on lines of code in a Pull Request, searching the site and on and on.

Changing the Status of a Pull Request

There is one final example we’ll look at since it’s really useful if you’re working with Pull Requests. Each commit can have one or more statuses associated with it and there is an API to add and query that status.

Most of the Continuous Integration and testing services make use of this API to react to pushes by testing the code that was pushed, and then report back if that commit has passed all the tests. You could also use this to check if the commit message is properly formatted, if the submitter followed all your contribution guidelines, if the commit was validly signed — any number of things.

Let’s say you set up a webhook on your repository that hits a small web service that checks for a Signed-off-by string in the commit message.

require 'httparty'

require 'sinatra'

require 'json'

post '/payload' do

push = JSON.parse(request.body.read) # parse the JSON

repo_name = push['repository']['full_name']

# look through each commit message

push["commits"].each do |commit|

# look for a Signed-off-by string

if /Signed-off-by/.match commit['message']

state = 'success'

description = 'Successfully signed off!'

else

state = 'failure'

description = 'No signoff found.'

end

# post status to GitHub

sha = commit["id"]

status_url = "https://api.github.com/repos/#{repo_name}/statuses/#{sha}"

status = {

"state" => state,

"description" => description,

"target_url" => "http://example.com/how-to-signoff",

"context" => "validate/signoff"

}

HTTParty.post(status_url,

:body => status.to_json,

:headers => {

'Content-Type' => 'application/json',

'User-Agent' => 'tonychacon/signoff',

'Authorization' => "token #{ENV['TOKEN']}" }

)

end

end

Hopefully this is fairly simple to follow.

In this web hook handler we look through each commit that was just pushed, we look for the string Signed-off-by in the commit message and finally we POST via HTTP to the /repos/<user>/<repo>/statuses/<commit_sha> API endpoint with the status.

In this case you can send a state (success, failure, error), a description of what happened, a target URL the user can go to for more information and a “context” in case there are multiple statuses for a single commit. For example, a testing service may provide a status and a validation service like this may also provide a status — the “context” field is how they’re differentiated.

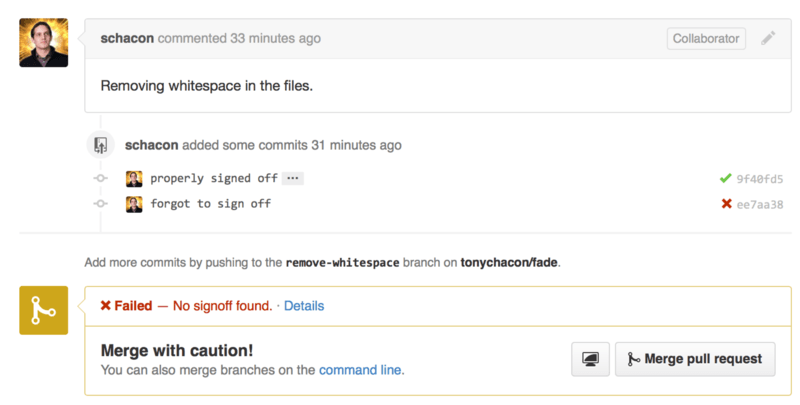

If someone opens a new Pull Request on GitHub and this hook is set up, you may see something like Figure 6-55.

You can now see a little green check mark next to the commit that has a “Signed-off-by” string in the message and a red cross through the one where the author forgot to sign off. You can also see that the Pull Request takes the status of the last commit on the branch and warns you if it is a failure. This is really useful if you’re using this API for test results so you don’t accidentally merge something where the last commit is failing tests.

Octokit

Though we’ve been doing nearly everything through curl and simple HTTP requests in these examples, several open-source libraries exist that make this API available in a more idiomatic way.

At the time of this writing, the supported languages include Go, Objective-C, Ruby, and .NET.

Check out http://github.com/octokit for more information on these, as they handle much of the HTTP for you.

Hopefully these tools can help you customize and modify GitHub to work better for your specific workflows. For complete documentation on the entire API as well as guides for common tasks, check out https://developer.github.com.

Summary

Now you’re a GitHub user. You know how to create an account, manage an organization, create and push to repositories, contribute to other people’s projects and accept contributions from others. In the next chapter, you’ll learn more powerful tools and tips for dealing with complex situations, which will truly make you a Git master.